Chagall (and other) Tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince

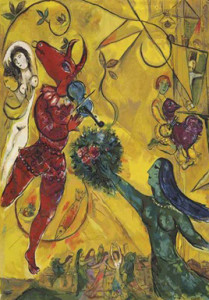

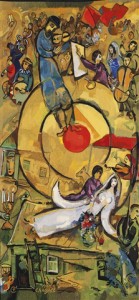

The name Yvette Cauquil-Prince is virtually synonymous with the term “Marc Chagall tapestry.”

After all, Chagall didn’t spend years mastering the ancient craft of weaving and then sit working at a loom, day after day, for months at a time. Someone else had to do that, and for Chagall — as with artists and their estates including Picasso, Leger, Calder, Kandinsky, Klee, Ernst, de St. Phalle, Brassai and Matta — it was Yvette Cauquil-Prince.

The Belgian-born Cauquil-Prince was Chagall’s best option to continue to explore the medium of tapestry which he had become enamored with after completing a series of tapestries commissioned by the state of Israel. The Chagall tapestries that still decorate the state reception hall of the Knesset had been woven by the Gobelins, the famous French “Manufacture Royale” which was set up by Louis XIV but to this day only takes on gifts of state. Happily Madeline Malraux, the wife of the France’s Cultural Minister Andre Malraux, was acquainted with Yvette Cauquil-Prince and made the introductions.

Chagall was wary at first, demanding that their first effort be destroyed if he didn’t like it. Yvette had a condition of her own — that it be destroyed if SHE found it wanting. Happily both were delighted, and they embarked on a long collaboration and friendship so close that Chagall referred to Yvette as his spiritual daughter. As had Picasso, the artist allowed Yvette to choose the images to be translated into tapestry and didn’t interfere with her interpretive cartooning or weaving as it progressed. After Chagall’s death Yvette remained close to the artist’s family and with their approval continued to create Chagall tapestries, something that Chagall himself had said he wanted. “When I am no longer here, you must continue the work,” he told her. “There will never be a tapestry by Chagall without you.”

Altogether there were only about forty Chagall tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince, some of them monumental in size, all of them very small editions or unique (though “editions of one” often provided for an artist proof reserved for the Chagall family). She didn’t actually weave most of these pieces herself. Early in her career Yvette had developed a complex shorthand code by which other weavers in her employ could execute her complex Coptic-influenced interpretative designs — the blueprints that made a Chagall tapestry a Chagall tapestry. By the end of her life in 2005 it could take Yvette up to a year to complete one of these “cartoons” for tapestry.

Cauquil-Prince was recognized by the Louvre as a great artist in her own right, and her Chagall tapestries are widely honored in important private and public collections throughout the world. Because such tapestries are much rarer than Chagall paintings the temptation is to call them “priceless” since they rarely come up for public sale. However, everything has its price and during her lifetime most of Cauquil-Prince’s tapestries were for sale (this was how she made her living). They come back onto the market from time to time.

Two of arguably the most beautiful small Chagall tapestries recently appeared at auction. “Liberation” was withdrawn from Sotheby’s New York sale of November 7, 2013. Perhaps the consignor was nervous about it making the presale estimate of $200,000 – $300,000 and sold it privately before the auction. If so, he may have acted too quickly, judging by the very comparable “La Danse” tapestry, which sold at Christie’s London on February 5, 2015, for the equivalent of $306,621 USD. The presale estimate for La Danse was $152,928 – 229,392 USD, reflecting the lower prices that tapestries by other important artists have recently achieved. All tapestries are not created equal, of course. In the last ten years three other small Chagall tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince have sold at auction at prices between about $30,000 – $80,000, and one monumental masterpiece brought $385,000 – still the auction record for a Chagall tapestry.

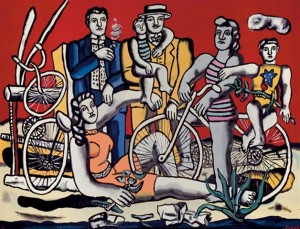

Cauquil-Prince and Chagall were so attuned that Chagall himself declared upon seeing one of her efforts, “This is a real Chagall. It is my hands that did all this.” Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Yvette’s Chagall tapestries sell for higher prices than her interpretations of the works of other artists. However, it would be hard to make a case that Cauquil-Prince’s weaving of Leger’s “Les loisirs sur fond rouge” isn’t a spectacular tapestry. Why, then, did it sell at auction for 45% less than the top Chagall? It’s not like Leger is somehow a less important or desirable artist, at least in terms of public sales of paintings. The highest price for a Chagall painting at auction was $14,850,000 versus $39,241,000 for the top Leger lot. If you add up the top ten auction sales for each artist Leger still wins hands down — his top ten sales add up to nearly $176,000,000 versus just $100,000,000 for Chagall.

I often write about value mysteries and in many ways every sale of a work of art qualifies as a mystery. It’s no more strange that Yvette’s Chagall tapestries bring more at auction and than her Legers than the fact that Chagall tapestries are sometimes priced 1000% higher in galleries than they likely can be resold for at auction. However, the real mystery has to do with the tapestries that Yvette Cauquil-Prince created with Max Ernst.

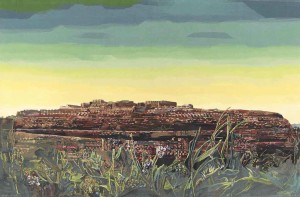

Monumental Max Ernst tapestry by Yvette Cauquil-Prince: “La ville entière” – 111 7/8 x 169 1/2 inches

Ernst (2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976), was a German born Dadaist/Surrealist. His work can be seen numerous important museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim, the Hirshhorn, Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the St. Louis Art Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art and on and on. He sells well at auction. Ernst’s top sale was $16,322,500 vs, $14,850,000 for Chagall, though if you look at the top ten auction prices Chagall thrashes Ernst two to one (why auction prices can be hugely deceptive indicators will be to subject of a future post).

Yvette Cauquil-Prince’s collaboration with Max Ernst actually came about smack in the middle of her triumphant work with Chagall. Chagall called Yvette “my little girl” once too often in front of his jealous wife, Vava, and she banished Cauquil-Prince from working with her husband for a decade. In 1978 Yvette came back to Milwaukee where she had been greeted so warmly upon completion of the Jewish Museum’s Chagall, to present her ten Max Ernst masterpieces,which then toured to Los Angeles and Philadelphia.

Like her Chagall tapestries, Cauquil-Prince’s Max Ernst masterpieces were beautifully interpreted, monumental in scale and woven in very small editions, some of them unique. Because of the difficulty and time-consuming nature of the cartooning and because Cauquil-Prince had to maintain an entire atelier of artisans to weave her pieces on Corsica, it’s likely that the prices for the finished tapestries were comparable to what she had asked for her Chagalls.

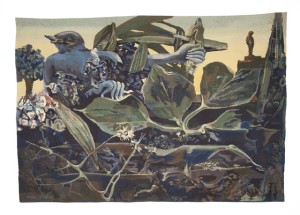

Ernst’s “La nature à l’aurore” tapestry (76.4 x 106.2 inches) woven by Cauquil-Prince did not fare well at auction

What makes an artist “important” and “desirable” doesn’t necessarily equate to demand across different markets. For collectors of Surrealism, important paintings by Ernst are very desirable. For an American living in the mid-West who is decorating his home, a beautiful tapestry by the famous Chagall is a lot more desirable than some beautifully weird and disturbing tapestry by Max Ernst, who is not exactly a household name in the USA. Still, you’d think that an Yvette Cauquil-Prince Ernst tapestry would be worth at least half as much as a Chagall or even a Leger, wouldn’t you?

But you’d be wrong. Not to be cynical, but value doesn’t necessarily have much to do with price, whether at auction or in galleries (it was Oscar Wilde who wrote that “a cynic is a man who knows the price of everything but the value of nothing”). The day after the small Chagall “La danse” sold in London for the equivalent of $308,000 against an estimate of 100,000 – 150,000 GBP, a monumental (111 7/8 x 169 1/2 inches) Cauquil-Prince Max Ernst tapestry, “La ville entière” was passed a few miles away at Christie’s South Kensington against an estimate of just 10,000 – 15,000 GBP — about $16,000 to $24,000!

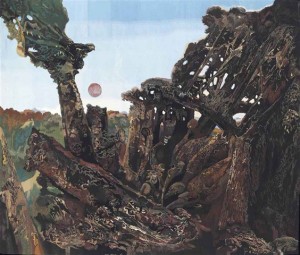

“Totem et Tabou” – Max Ernst tapestry by Yvette Cauquil-Prince measuring a gigantic 163.4 x 194.9 inches

It’s tempting to think that this was some kind of bizarre fluke, but in fact Cauquil-Prince tapestries by Max Ernst have a history of making prices vastly lower than what it would cost to weave them. Christie’s didn’t just pull their estimate out of a hat, it was probably based on Cauquil-Prince’s weaving of Ernst’s “La nature à l’aurore” which sold at Sotheby’s New York on December 15, 2014 for just $22,500. And it’s not like Sotheby’s was throwing their piece away — they had offered it at an estimate of $25,000 – $35,000 on May 8, 2013 and it had failed to sell (it had brought $36,000 at a 2006 Christie’s sale). “Totem et Tabou,” which is the largest and arguably the most important of Cauquil-Prince Ernst tapestries, was passed at Christie’s London on February 7, 2013 with a much more aggressive estimate — 50,000 – 70,000 GBP (78,480 – 109,872 USD).

Bottom line, there just isn’t much demand for Max Ernst tapestries, Yvette’s talent notwithstanding, which to my mind makes them fantastic bargains (provided you like the work of Max Ernst). But auction results can be extremely deceptive indications of prices in the real world. Unless you have a time machine, knowing what was available last year (or yesterday) isn’t worth much. For thinly traded items like tapestries, the “spread” between bid and ask prices can vary wildly. Yes, “La ville entière” may have failed to get a $16,000 bid at Christie’s but it was snapped up within days after the sale. It may very well show up in some dealer’s possession tomorrow with an asking price of hundreds of thousands of dollars, which may be what it really is “worth” but would make it no bargain at all.