Mathes Missive from Moscow #11 – Friday: Just Another Day at the Fair

Good morning, Americans,

Here were are in Moscow, the 14th dirtiest city in the world (even New Delhi is cleaner), where a few nights ago according the newspaper police arrested a man leading a stolen horse through the city on a drunken rampage (probably it was the man who was drinking, not the horse), where the official inflation rate is approaching 15 percent (so you know it must be higher) and where our merry little band is ready for another day and another dollar (coming in for a change, one hopes, as opposed to going out).

We are beginning to settle into a routine, inasmuch as one can establish a routine in a situation like this. But any bit of structure helps when you need to focus all of your energy for an unpredictable day. You don’t want to worry about where to eat lunch after you write for four hours then have to dash off and deal with oligarchs all day. The only thing different I attempt this morning is to replace my bottle of evil-tasting cough syrup at the pharmacy down the street. You can tell they’re pharmacies because the signs say something like Anteka — maybe these are very old-fashioned medicines? Antiques? (The cough syrup is Greek, but probably not ancient.) Jane, in dog withdrawal, has been looking for small creatures to photograph and finally finds a stray. You don’t see strays in any other major European capital. Here the only dogs you see are strays.

Jane spends most of the afternoon trying to call Terri on the Russian telephone she has procured for her daughter. Recall all those happy hours we spent at the phone shop? Jane is very high on phones (c ounting her own Russian telephone, she herself is now carrying four). But Terri doesn’t answer. Nor does she answer her American telephone. Jane finally resorts to sending emails. “Call Mom. Bring sandwiches.”

ounting her own Russian telephone, she herself is now carrying four). But Terri doesn’t answer. Nor does she answer her American telephone. Jane finally resorts to sending emails. “Call Mom. Bring sandwiches.”

Julia still looks very nice and still isn’t feeling herself, despite another two hours of hot and cold baths last night in Jane’s room.

“I will have to find a Russian bathhouse where they beat you,” she declares.

I have this vague recollection of my brother Gary telling me how they used to do something like this to you at the Schvitz in Cleveland, the traditional Jewish version of what Julia has in mind. Hard to fit Julia in with the images I have of old farts kibitzing in the steam, while guys whack them on the back with bundles of twigs.

“They beat you with brooms?”

“Exactly.”

Poor Julia!

It’s a slow day and a relatively uneventful one (anything that actually did happen, art-wise, would of course be a secret). Here are some scenes of what the rest of the fair looks like.

During the afternoon several friends of Julia’s come by — she has given out many passes — and she has a good time showing them around the floor. At some point a Russian comes in with a question we can’t understand, and we need Julia. Jane calls her on my Russian telephone (Jane’s own Russian phone has now stopped working) but of course Julia has left her phone in the booth. Just as well; she had forgotten to charge it anyway.

During the afternoon several friends of Julia’s come by — she has given out many passes — and she has a good time showing them around the floor. At some point a Russian comes in with a question we can’t understand, and we need Julia. Jane calls her on my Russian telephone (Jane’s own Russian phone has now stopped working) but of course Julia has left her phone in the booth. Just as well; she had forgotten to charge it anyway.

Jane has been insisting that sharing her hotel room with Julia is no trouble (“She’s just like a daughter, there are towels on the floor all over the place”), but at the same time has been working overtime trying to get Julia a room of her own in the hotel. Finally the hotel manager has been able to accomplish this, but only for over the weekend. The room rate is excellent, and he even gives us all a good discount for the weekend and free breakfasts — but on Monday all bets will be off again. Moscow is 100% full.

Terri shows up at last, close to six o’clock. She has brought strawberries this time. From Zum. The berries are smaller and not as red as the ones you can get in any American supermarket, but like most of the food we’ve had here, they somehow taste better. In fact Terri says they are the best strawberries she has ever eaten. Terri’s American telephone doesn’t work because she has brought the wrong charger. Jane demands to see her daughter’s Russian telephone and eventually figures out that Terri has somehow turned it off. This is why Jane’s telephone didn’t work either – she had turned hers off, too. (My phone works great, but I have no one to call.)

Terri shows up at last, close to six o’clock. She has brought strawberries this time. From Zum. The berries are smaller and not as red as the ones you can get in any American supermarket, but like most of the food we’ve had here, they somehow taste better. In fact Terri says they are the best strawberries she has ever eaten. Terri’s American telephone doesn’t work because she has brought the wrong charger. Jane demands to see her daughter’s Russian telephone and eventually figures out that Terri has somehow turned it off. This is why Jane’s telephone didn’t work either – she had turned hers off, too. (My phone works great, but I have no one to call.)

After a few more invigorating hours of mother-daughter combat, staring off into space, and secret art doings (we did meet some interesting people, however), it is nine o’clock and a voice over the loudspeaker announces that the fair is now over for the night. Apparently they have decided upon a closing time. Immediately guards spread out and order everyone (including us) to leave.

Oh, did I mention that at eight o’clock this Friday night, the French technical person came by our booth with a bill for the electrics? Just the kind of thing you want to deal with over the weekend. And it is so a la carte as to boggle the mind. They’re even charging for the wooden struts (I think there are something like 59 of them) that are stretched across the top of the booth, above the fabric ceiling, to which the lighting tracks are attached. It’s like being billed for every spoon, fork, plate and napkin you’ve used in a restaurant — to say nothing about the number of flakes of pepper and grains of salt! Oh, and unless you have spent the funds on a new car, the bill must be paid in full by Monday. Your art will be held hostage until the funds clear.

Marat cannot meet us tonight — he has to pick up his aunt from the airport. Julia and I want to walk to the Cafe Pushkin, where we will be having dinner with John from Bloomberg, but Jane and Terri prefer to be driven. Julia, who once got stopped by the police for trying to hitchhike through Queens (“We don’t do that kind of thing here, honey,”) flags down a gypsy cab, plenty of which cruise the Moscow streets (if you think you can just stick out your hand and hail a regular cab here the way we do in New York, you’re going to be sadly disappointed). The driver is from Kazakhstan or some such place and takes us to Pushkin something-or-other, but not Cafe Pushkin (maybe this is where Marat was the other day, when we were waiting at the Pushkin Museum.) We then spend the next half hour tooling around central Moscow trying to find the restaurant — it doesn’t help that if you guess the wrong street you can’t make a turn for six miles.

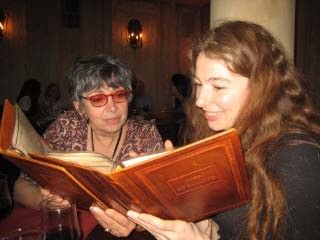

Finally we arrive. Terri has selected Cafe Pushkin because the magazine for American Express Platinum Card holders has mentioned it as being one of THE places to go in Moscow. Terri goes to all the IN places. It is a beautiful old building and the 18th century Rococo interior inside looks sparkling, authentic, 100% old Russia. If John, who meets us at the bar, hadn’t told us it is all in fact 100% brand new, built within the last few years (at phenomenal expense) to look old, we would never have known.

Finally we arrive. Terri has selected Cafe Pushkin because the magazine for American Express Platinum Card holders has mentioned it as being one of THE places to go in Moscow. Terri goes to all the IN places. It is a beautiful old building and the 18th century Rococo interior inside looks sparkling, authentic, 100% old Russia. If John, who meets us at the bar, hadn’t told us it is all in fact 100% brand new, built within the last few years (at phenomenal expense) to look old, we would never have known.

It’s not hard to understand why John is so successful as an art writer here in Russia. He freelances for a number of different publications and from the stories of his we’ve seen — including the piece featuring us on Bloomberg — it’s clear that he’s a talented writer. But John seems to be something more. He’s a quiet, lovely guy with an open mind, a happy heart and apparently no axes to grind. We don’t understand why he’s been so nice to us — he now says that he’s even influenced the folks at Reuters where he used to work to give us more coverage — but it’s certainly a pleasure to have the chance to be nice to him. John has wonderful stories to tell, and — as if you couldn’t guess the secret of being a good writer — he is a very good listener.

As we wait at the bar for a table, Terri, herself a good talker, zeroes in and starts chatting him up. Sitting in a Ukrainian restaurant in front of a plate of lard, Terri perhaps seemed a trifle ridiculous . Here in this glittering setting among Moscow’s beautiful people, everything about her suddenly makes perfect sense. This is her natural habitat. Not that Jane or I or Julia don’t like Cafe Pushkin. We can swim in these waters, too; we’re all good swimmers. But I for one prefer Cafe Babai. Interestingly enough, John from Bloomberg when we told him that we were coming here didn’t think of it as the best place in Moscow — sort of like the Tavern on the Green in Manhattan. “Definitely you have to go once if you haven’t been there, but there are probably a lot of better places if what you want is good food.”

As we wait at the bar for a table, Terri, herself a good talker, zeroes in and starts chatting him up. Sitting in a Ukrainian restaurant in front of a plate of lard, Terri perhaps seemed a trifle ridiculous . Here in this glittering setting among Moscow’s beautiful people, everything about her suddenly makes perfect sense. This is her natural habitat. Not that Jane or I or Julia don’t like Cafe Pushkin. We can swim in these waters, too; we’re all good swimmers. But I for one prefer Cafe Babai. Interestingly enough, John from Bloomberg when we told him that we were coming here didn’t think of it as the best place in Moscow — sort of like the Tavern on the Green in Manhattan. “Definitely you have to go once if you haven’t been there, but there are probably a lot of better places if what you want is good food.”

Terri, though, could probably eat here every night. She warns me to take some caviar fast, or she’s going to appropriate it all (how could we come to Moscow and not have caviar? And who better to share it with than John?).

I let Julia help me select an entree as usual, but it would be hard to make a real mistake. The food, needless to say, is rather rich.

It is nearing one thirty in the morning when we finally finish dinner. Marat is waiting outside, all dressed up from seeing his aunt, and happy to see us. We offer John a lift, but he prefers to walk. We had been told that Moscow was a dangerous city, but I guess it’s like New York — any of us wouldn’t be afraid to walk around at night in New York. We live there. We know where to go and where not to go.

As we drop Terri off at the Savoy, she announces that she has changed her plane reservation and is leaving tomorrow morning, not Sunday as planned. She wants to have a day to decompress in New York before going back to work. Terri and Julia had made plans to go to a design fair elsewhere in the city tomorrow morning, but I guess that’s out now. Jane was anticipating another happy day of butting heads (at one point Jane announces that if Terri rolls her eyes one more time, she’s going to get throttled). But Terri is Terri; she’s sampled all she needs to sample in Moscow and is ready to move on. Marat agrees to pick her up tomorrow at 6:30 a.m., even though he won’t get home tonight until very late indeed — what a mensch.

An instant later Terri waves goodbye and disappears into the grand lobby of her hotel. Our time together is over. Funny, I think we might actually miss her.