Value Mysteries: The Case of the Runaway Picasso Bull

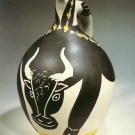

Working at the Madoura Pottery in the village of Vallauris in the South of France Pablo Picasso hand-decorated over four thousand ceramics between 1947 and his death in 1973. Over 600 of these were selected to be replicated in editions of 25 to 500 by the artisans at the Pottery and sold inexpensively to the tourists. For the last thirty some years they have been bought and sold at auctions and in galleries around the world. Studying these sales can bring fascinating insights into markets in general and the art world in particular.

Market inefficiency drives price volatility and, as with many markets, there are three factors that create inefficiency for Picasso ceramics: lack of knowledge, thin trading and what some people might call manipulation but which in reality is simply the interaction of small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.

Ironically, until recently the highest prices for Edition Picasso ceramics were achieved in the 1980s when the Japanese appeared to be on the verge of taking over the world. At the beginning of the decade it was the Japanese who knew something that everyone else didn’t: that ceramics had always been the true fine art in Japan, a culture where oil painting had not traditionally existed. Tremendous wealth was flowing toward Japan and the Japanese wanted to experience the best that the Old World had to offer in luxury products, fashion, food, entertainment and of course art. Well-heeled Japanese who weren’t rich enough to buy important European paintings could pay twice the asking price for a Picasso plate and feel they had gotten a tremendous bargain. Prices soared. By mid-decade Sotheby’s and Christie’s, which for years had turned up their noses at Picasso ceramics as mere tourist curiosities, began to include them in sales. Prices went even higher. Yet few people understood what these items were, where they were made, who made them and how many were created.

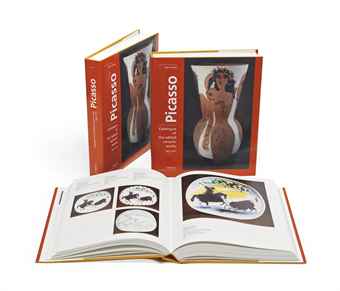

Because Picasso ceramics were low-priced vacation “souvenirs,” there was little published information available. Not even the book written by the owner of the Madoura Pottery, Georges Ramié (which was only available in French for several years), offered much hard data. Georges Ramié’s “Ceramiques de Picasso” pictured various of Picasso’s unique prototypes without explaining that there were perhaps hundreds of “authentic replicas” of the pictured pieces. This inevitably led to confusion among buyers and sellers alike as to whether ceramics were originals or edition pieces (in fact the vast majority of ceramics decorated personally by Picasso were never for sale and are still owned by members of the Picasso family and museums).

When this Bull appeared at auction it was probably the first time that anyone in the prestigious sale rooms had ever seen anything like it. But novelty wasn’t the only reason that this Bull sold at Sotheby’s London on October 18, 1990 for 44,000 British Pounds, then the equivalent of $87, 824. Knowing that the Japanese were voraciously pursuing Picassos a dealer may have made the top bid for this ceramic, figuring he could sell it to some rich fool in Tokyo. It only takes two bidders to achieve a record auction price and unknowingly the buyer might have been bidding against the one Japanese collector who would have paid a top retail price for this ceramic. Or perhaps there was a second dealer who thought he too was smarter than everyone else, was willing to take risks and believed there was no limit to the Japanese mania for Picasso ceramics. We’ll never know. What we do know is  that one month later, on November 19, 1990 another Picasso ceramic Bull just like the first sold for $39,600 at Christie’s in New York City.

that one month later, on November 19, 1990 another Picasso ceramic Bull just like the first sold for $39,600 at Christie’s in New York City.

A 55% decline in one month would be considered a crash in any market (the great Stock Market Crash in 1929 was a mere 12.82%). Certainly one factor in the price decline was lack of information, but that was about to change — sort of. In 1989 Alain Ramié, the son of Georges, published “Picasso – Catalogue of the Edited Ceramic Works.” I say “sort” of because both Georges and Alain Ramié’s books were popularly referred to as the Ramié Catalogue and to this day they are confused with one another. Each gave numbers to the pictures of Ceramics they included but the only Ramié numbers that now mean anything to dealers, collectors and auction houses are the numbers from Alain Ramié’s book. It is an authoritative catalogue raisonne compiled from the records of the Madoura Pottery and includes definitive measurements, descriptions, edition sizes and pictures. Sometimes (but not always) these numbers are referred to as AR numbers. Thus the professional shorthand for this Bull is R 255 or Ramié 255 or AR 255.

Around the time of the record 1990 sale anyone with access to the Alain Ramié catalogue would have known that the Bull was one of an edition of 100. In fact that’s how Sotheby’s identified it in the auction catalogue, but clearly the bidders weren’t aware of or discounted this information. In fact edition size is a problematic fact. After all, it’s not like there are actually 100 of these ceramics available for sale at the time of any given auction — there is only one. It might be years or even decades before another appears for sale (then again, it could be weeks). Of course there’s nothing like a record sale to alert all of the other owners of a similar item that now may be a good time to sell — often gaggles of similar pieces suddenly appear out of the woodwork at the next sale once a record has been achieved.

how Sotheby’s identified it in the auction catalogue, but clearly the bidders weren’t aware of or discounted this information. In fact edition size is a problematic fact. After all, it’s not like there are actually 100 of these ceramics available for sale at the time of any given auction — there is only one. It might be years or even decades before another appears for sale (then again, it could be weeks). Of course there’s nothing like a record sale to alert all of the other owners of a similar item that now may be a good time to sell — often gaggles of similar pieces suddenly appear out of the woodwork at the next sale once a record has been achieved.

In the stock market there are millions of shares, and the “spread” between the bid and ask prices can be a fraction of a penny. However, for thinly traded items the spread can be enormous. In hot markets this may work to the seller’s advantage: you might have multiple bids on your million dollar Miami Beach condo in 2007. But if the buyers suddenly disappear like they did for Florida real estate in 2009 you may have one offer and it might be for $400,000. This is what happened to the artworld when the Japanese “Bubble Economy” burst. The music suddenly stopped, the Japanese buyers disappeared, seemingly from one day to the next. Just as with people holding Collateralized Mortgage Obligations in October 2008, anybody who hadn’t already found a “greater fool” to sell to was stuck.

If the underbidder felt bad about losing the Bull at Sotheby’s October 1990 sale, he probably felt a lot better after the Christie’s sale the next month. And the buyer who bought the Ramié 255 Bull at a 55% discount (perhaps the same underbidder?) may have thought he was a genius. He would have been mistaken. The following year, on November 4, 1991, a Bull sold for $24,200, again at Christie’s in New York, nearly 40% less than the “bargain” November 1990 price. (Of course any dealer with a Bull of his own had immediately raised the price of the one in his shop to at least the $87,000 after the October 1990 Christie’s sale and many never adjusted their price downward — but this will be another post.)

Nearly twenty years later the Picasso Edition Ceramic Bull AR 255 was still changing hands at about the same price it brought in 1991 (one sold at Sotheby’s New York on October 29, 2010 for $25,000).

You would think that the market is more efficient these days, wouldn’t you? That lack of information is no longer an issue, that edition sizes have been discounted in the prices, and that mature markets like the long-standing one for Picasso ceramics can’t suffer from small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.

You would think that the market is more efficient these days, wouldn’t you? That lack of information is no longer an issue, that edition sizes have been discounted in the prices, and that mature markets like the long-standing one for Picasso ceramics can’t suffer from small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.

How then would you explain the Edition Picasso Ceramic Bull that sold on June 25, 2012, just a year and half after a two-decade string of $25,000 – 35,000 sales, for 97,250 British pounds at Christie’s South Kensington, then equal to $151,263?

I’ll try in my next post.