Value Mysteries: Jean Lurçat Tapestry Screen

Most dealers and auction houses don’t have a lot of knowledge about tapestries by 20th centuries artists. This makes for a very inefficient, thinly traded market — exactly the type of environment in which smart people can make big profits. Aubussons by Alexander Calder are sometimes still estimated for $2,000 – $3,000 as they were twenty years ago. Though the final hammer prices generally are much higher if word gets out, sometimes no one recognizes what bargains can be had.

Calder didn’t sit down at a loom for months weaving those “Calder” tapestries, of course. He didn’t even see most of them — tapestries are multiples, and Aubussons were generally woven in editions of six with two authorized artist proofs. Long after Calder died, the ateliers were still completing these editions.

It wouldn’t be correct to call tapestry ateliers “factories,” but since they were established by Louis XIV in the 17th Century the “Manufactures Royales” of Aubusson have been businesses that must charge a certain amount per square foot in order to cover salaries, cost of materials, administrative overhead, payment to the artist and profit. Sometimes the marketplace bestows a premium above and beyond what it would cost to replace a tapestry from the weaver. This is especially true for tapestries by Brand Name artists like Picasso, Chagall, Miro, Leger that were woven years ago and the editions are closed out. Here, the line between decorative art and fine art begins to blur and tapestries become rare and collectible artifacts, like first editions by important authors. Tapestries by lesser-knowns, on the other hand, can sometimes be purchased for a fraction of their replacement cost — like used books by forgotten writers.

This tapestry by Saint Saens, an artist influenced by Lurcat, was recently on sale in a retail gallery for less than $10,000

One of the most important names in the tapestry world of the mid-20th century was French artist Jean Lurçat. Lurçat was not a weaver himself but he became a master of the medium and inspired scores of important French artists of the period to work in tapestry, which had been a dying art form.

Between 1900 and 1910 the average annual output of the world-famous Beauvais tapestry workshops was a mere 20 square metres because the weaving costs had risen as high as 38,000 francs per square metre, roughly $60,000 in today’s dollars! Lurçat rescued the Aubusson tapestry ateliers practically single-handedly by simplifying design and production requirements. His innovations brought costs back down to earth and the Aubusson ateliers sprang to life in the 1940s once weaving became profitable again.

Lurçat, however, is not a name known to most Americans. His tapestries and those by important artists who followed his lead are usually sold as decorative pieces with none of the fine art premium that attaches to Calders, Sonia Delaunays and the like. Thus beautiful tapestries by René Perrot, Jean Picart le Doux, Mario Prassinos and Jean Lurçat himself can be found in retail galleries for prices in four figures – far less than the cost of weaving, which it could be argued is their intrinsic value.

Fine art tapestries like other works of art are not commodities. One Miro tapestry is not the same as any other any more than all Picasso paintings are interchangeable in value like pork bellies or ounces of silver. Nor are auction prices reliable indicators of value, though they can provide useful insights.

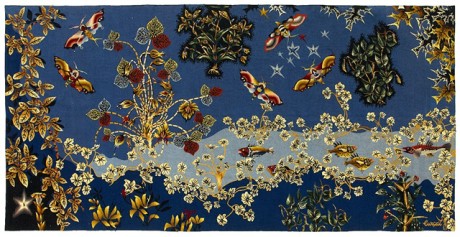

Take this Lurçat tapestry for instance. “Papillons de Nuits” is a large, fairly typical Lurçat measuring 68.1 x 135.8 inches. It sold under estimate at the Van Ham Kunstauktionen auction in Germany on 1 December 2011 for the equivalent of about $6,000.

“Papillons de Nuits” is a large, fairly typical Lurçat measuring 68.1 x 135.8 inches. It sold under estimate at the Van Ham Kunstauktionen auction in Germany on 1 December 2011 for the equivalent of about $6,000.

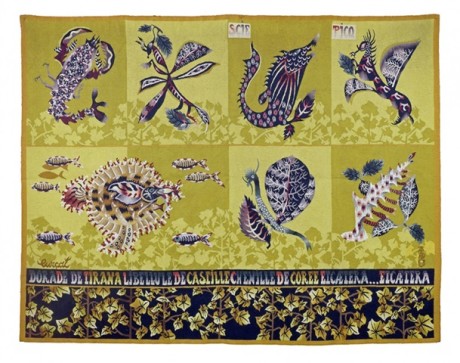

Here’s another, arguably a “better” Lurçat tapestry. Auction records show that “Scie Pick,” 60.2 x 120.5 inches, was passed at Éric Pillon Enchères auction in France of October 26, 2014 against an estimate of 7 – 8,000 Euros (8,868 – 10,135 USD). Another tapestry that looks just like this one but measured only 60.2 x 78.7 inches sold at Drouot-Estimations in Paris on June 13, 2014, for 4,100 EUR (5,544 USD) Hammer. While modern Aubussons are generally limited to a total of eight pieces as indicated above, select tapestries were sometimes “re-editioned” in different sizes — a way of capitalizing on the more successful images (and making them not quite as “rare” as edition sizes would seem to indicate).

Here’s another, arguably a “better” Lurçat tapestry. Auction records show that “Scie Pick,” 60.2 x 120.5 inches, was passed at Éric Pillon Enchères auction in France of October 26, 2014 against an estimate of 7 – 8,000 Euros (8,868 – 10,135 USD). Another tapestry that looks just like this one but measured only 60.2 x 78.7 inches sold at Drouot-Estimations in Paris on June 13, 2014, for 4,100 EUR (5,544 USD) Hammer. While modern Aubussons are generally limited to a total of eight pieces as indicated above, select tapestries were sometimes “re-editioned” in different sizes — a way of capitalizing on the more successful images (and making them not quite as “rare” as edition sizes would seem to indicate).

Auction prices can be greatly misleading, and it would be foolish to believe that somehow $5,000 or $6,000 “should” be the price of a Lurçat tapestry. In fact they have sold at much higher prices both at auction and in galleries.

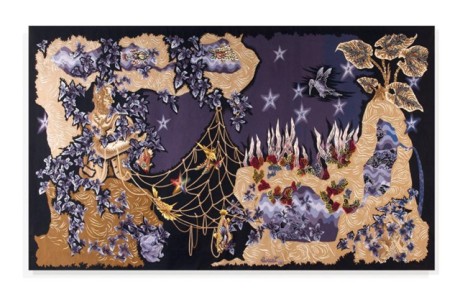

Jean Lurçat’s

“Chasse et pêche” measuring 81 x 140 inches sold at a French auction in 2011 for the equivalent of $44,000 – probably less than it would cost to have a similar piece woven today. In a retail gallery it would be priced much higher.

It’s not likely that most people looking for a large artwork to place on a wall in their home would have been considering tapestries when the above pieces sold inexpensively at auction, nor is it likely that Americans would have even found these particularly obscure sales. Even if you have a time machine, it’s not like you can actually buy these tapestries for the recorded auction prices — you will simply be able to make the next bid. Unless the actual buyer then just gives up, the price could go much higher. In fact many Lurçats have sold for much more at auction and in galleries, which is where most tapestries are sold to end users. Retail buyers generally need someone to explain why a tapestry might be better for them than a painting and time to consider the type of image and the size that might work in their home.

But the fact is that Lurçat is not a “hot” artist. There is not much demand for tapestries in general, let alone for tapestries by Lurçat. This is why most sell — even in retail galleries — for less than it would cost to weave them. To some people that would indicate “value” and “bargain.” Others would probably be thinking “White Elephant.”

So what would you call this Lurçat tapestry screen that I saw recently in the booth of a fashionable French gallery at a high end art and antiques fair in New York?

While it appears at first to be an eight panel screen, closer examination reveals that it is actual four two-piece panels, making it much easier to transport and set up. Actually it’s a pretty ingenious thing to do with very large horizontal tapestries like the ones illustrated above, which generally are harder to sell than smaller pieces which can be more easily placed. In fact this screen is 90.5 x 220.5 inches — over 18 feet across!

While it appears at first to be an eight panel screen, closer examination reveals that it is actual four two-piece panels, making it much easier to transport and set up. Actually it’s a pretty ingenious thing to do with very large horizontal tapestries like the ones illustrated above, which generally are harder to sell than smaller pieces which can be more easily placed. In fact this screen is 90.5 x 220.5 inches — over 18 feet across!

Such a huge tapestry was probably commissioned for a specific space — this is not the type of thing you weave on spec and then hope to find someone with a gigantic room they want to hang a tapestry in. Perhaps when the original owner died somebody needed to be creative in order to sell this gigantic thing and had it mounted. However, the woman in the booth at the fair explained imperious tone that this was designed by Lurçat specifically to be a screen, in fact it was the only such screen he ever created.

When I asked if there was some documentation for this claim I was given the look that dealers reserve for Martians and other ignoramuses. Obviously if I were one of those crazy Americans obsessed with minutia, I wasn’t a likely prospect to buy anything. Especially a rare tapestry screen like this one priced at $160,000!

Well, maybe the story was true, maybe it wasn’t. However, the bottom line of value is always determined by supply and demand. There were hundreds, possibly thousands of Lurçat tapestries woven; few people are looking specifically for this type of thing, hence prices are often below intrinsic cost. However, this smart French dealer is trying to change the equation. He’s saying that the supply is not thousands but — if you believe the story — only one. And while demand by knowledgeable buyers of tapestries for an impossibly large Lurçat is minimal, a lot of rich people on Park Avenue with big walls and collectors of trendy Mid-Century Modernism shop at prestigious art and design fairs. They’ve probably never seen anything like this (partly because they don’t shop in those places where Lurçat tapestries can be purchased for less than $10,000).

Whether the screen sold for anywhere near the asking price or at all, I do not know. What I do know is that somebody bought this very same Lurçat at Sotheby’s Paris on November 26, 2013 for a little more than $20,000. The Value Mystery is whether the French dealer will be able to sell it, how long will it take, and how much will it finally bring? At full price somebody stands to make a 700% profit in a year, but that $160,000 probably is not a great deal higher than it would cost to weave such a tapestry today.

So what about this other Lurçat tapestry screen measuring a much more practical 89 x 32 inches that sold at the Leland Little Auction & Estate Sale of March 17, 2012, for a total price of $2,000? What kind of value should be placed on it?

So what about this other Lurçat tapestry screen measuring a much more practical 89 x 32 inches that sold at the Leland Little Auction & Estate Sale of March 17, 2012, for a total price of $2,000? What kind of value should be placed on it?