Mathes Missive from Moscow #11 – Friday: Just Another Day at the Fair

Good morning, Americans,

Here were are in Moscow, the 14th dirtiest city in the world (even New Delhi is cleaner), where a few nights ago according the newspaper police arrested a man leading a stolen horse through the city on a drunken rampage (probably it was the man who was drinking, not the horse), where the official inflation rate is approaching 15 percent (so you know it must be higher) and where our merry little band is ready for another day and another dollar (coming in for a change, one hopes, as opposed to going out).

We are beginning to settle into a routine, inasmuch as one can establish a routine in a situation like this. But any bit of structure helps when you need to focus all of your energy for an unpredictable day. You don’t want to worry about where to eat lunch after you write for four hours then have to dash off and deal with oligarchs all day. The only thing different I attempt this morning is to replace my bottle of evil-tasting cough syrup at the pharmacy down the street. You can tell they’re pharmacies because the signs say something like Anteka — maybe these are very old-fashioned medicines? Antiques? (The cough syrup is Greek, but probably not ancient.) Jane, in dog withdrawal, has been looking for small creatures to photograph and finally finds a stray. You don’t see strays in any other major European capital. Here the only dogs you see are strays.

Jane spends most of the afternoon trying to call Terri on the Russian telephone she has procured for her daughter. Recall all those happy hours we spent at the phone shop? Jane is very high on phones (c ounting her own Russian telephone, she herself is now carrying four). But Terri doesn’t answer. Nor does she answer her American telephone. Jane finally resorts to sending emails. “Call Mom. Bring sandwiches.”

ounting her own Russian telephone, she herself is now carrying four). But Terri doesn’t answer. Nor does she answer her American telephone. Jane finally resorts to sending emails. “Call Mom. Bring sandwiches.”

Julia still looks very nice and still isn’t feeling herself, despite another two hours of hot and cold baths last night in Jane’s room.

“I will have to find a Russian bathhouse where they beat you,” she declares.

I have this vague recollection of my brother Gary telling me how they used to do something like this to you at the Schvitz in Cleveland, the traditional Jewish version of what Julia has in mind. Hard to fit Julia in with the images I have of old farts kibitzing in the steam, while guys whack them on the back with bundles of twigs.

“They beat you with brooms?”

“Exactly.”

Poor Julia!

It’s a slow day and a relatively uneventful one (anything that actually did happen, art-wise, would of course be a secret). Here are some scenes of what the rest of the fair looks like.

During the afternoon several friends of Julia’s come by — she has given out many passes — and she has a good time showing them around the floor. At some point a Russian comes in with a question we can’t understand, and we need Julia. Jane calls her on my Russian telephone (Jane’s own Russian phone has now stopped working) but of course Julia has left her phone in the booth. Just as well; she had forgotten to charge it anyway.

During the afternoon several friends of Julia’s come by — she has given out many passes — and she has a good time showing them around the floor. At some point a Russian comes in with a question we can’t understand, and we need Julia. Jane calls her on my Russian telephone (Jane’s own Russian phone has now stopped working) but of course Julia has left her phone in the booth. Just as well; she had forgotten to charge it anyway.

Jane has been insisting that sharing her hotel room with Julia is no trouble (“She’s just like a daughter, there are towels on the floor all over the place”), but at the same time has been working overtime trying to get Julia a room of her own in the hotel. Finally the hotel manager has been able to accomplish this, but only for over the weekend. The room rate is excellent, and he even gives us all a good discount for the weekend and free breakfasts — but on Monday all bets will be off again. Moscow is 100% full.

Terri shows up at last, close to six o’clock. She has brought strawberries this time. From Zum. The berries are smaller and not as red as the ones you can get in any American supermarket, but like most of the food we’ve had here, they somehow taste better. In fact Terri says they are the best strawberries she has ever eaten. Terri’s American telephone doesn’t work because she has brought the wrong charger. Jane demands to see her daughter’s Russian telephone and eventually figures out that Terri has somehow turned it off. This is why Jane’s telephone didn’t work either – she had turned hers off, too. (My phone works great, but I have no one to call.)

Terri shows up at last, close to six o’clock. She has brought strawberries this time. From Zum. The berries are smaller and not as red as the ones you can get in any American supermarket, but like most of the food we’ve had here, they somehow taste better. In fact Terri says they are the best strawberries she has ever eaten. Terri’s American telephone doesn’t work because she has brought the wrong charger. Jane demands to see her daughter’s Russian telephone and eventually figures out that Terri has somehow turned it off. This is why Jane’s telephone didn’t work either – she had turned hers off, too. (My phone works great, but I have no one to call.)

After a few more invigorating hours of mother-daughter combat, staring off into space, and secret art doings (we did meet some interesting people, however), it is nine o’clock and a voice over the loudspeaker announces that the fair is now over for the night. Apparently they have decided upon a closing time. Immediately guards spread out and order everyone (including us) to leave.

Oh, did I mention that at eight o’clock this Friday night, the French technical person came by our booth with a bill for the electrics? Just the kind of thing you want to deal with over the weekend. And it is so a la carte as to boggle the mind. They’re even charging for the wooden struts (I think there are something like 59 of them) that are stretched across the top of the booth, above the fabric ceiling, to which the lighting tracks are attached. It’s like being billed for every spoon, fork, plate and napkin you’ve used in a restaurant — to say nothing about the number of flakes of pepper and grains of salt! Oh, and unless you have spent the funds on a new car, the bill must be paid in full by Monday. Your art will be held hostage until the funds clear.

Marat cannot meet us tonight — he has to pick up his aunt from the airport. Julia and I want to walk to the Cafe Pushkin, where we will be having dinner with John from Bloomberg, but Jane and Terri prefer to be driven. Julia, who once got stopped by the police for trying to hitchhike through Queens (“We don’t do that kind of thing here, honey,”) flags down a gypsy cab, plenty of which cruise the Moscow streets (if you think you can just stick out your hand and hail a regular cab here the way we do in New York, you’re going to be sadly disappointed). The driver is from Kazakhstan or some such place and takes us to Pushkin something-or-other, but not Cafe Pushkin (maybe this is where Marat was the other day, when we were waiting at the Pushkin Museum.) We then spend the next half hour tooling around central Moscow trying to find the restaurant — it doesn’t help that if you guess the wrong street you can’t make a turn for six miles.

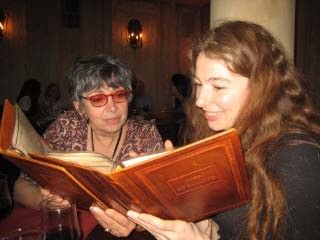

Finally we arrive. Terri has selected Cafe Pushkin because the magazine for American Express Platinum Card holders has mentioned it as being one of THE places to go in Moscow. Terri goes to all the IN places. It is a beautiful old building and the 18th century Rococo interior inside looks sparkling, authentic, 100% old Russia. If John, who meets us at the bar, hadn’t told us it is all in fact 100% brand new, built within the last few years (at phenomenal expense) to look old, we would never have known.

Finally we arrive. Terri has selected Cafe Pushkin because the magazine for American Express Platinum Card holders has mentioned it as being one of THE places to go in Moscow. Terri goes to all the IN places. It is a beautiful old building and the 18th century Rococo interior inside looks sparkling, authentic, 100% old Russia. If John, who meets us at the bar, hadn’t told us it is all in fact 100% brand new, built within the last few years (at phenomenal expense) to look old, we would never have known.

It’s not hard to understand why John is so successful as an art writer here in Russia. He freelances for a number of different publications and from the stories of his we’ve seen — including the piece featuring us on Bloomberg — it’s clear that he’s a talented writer. But John seems to be something more. He’s a quiet, lovely guy with an open mind, a happy heart and apparently no axes to grind. We don’t understand why he’s been so nice to us — he now says that he’s even influenced the folks at Reuters where he used to work to give us more coverage — but it’s certainly a pleasure to have the chance to be nice to him. John has wonderful stories to tell, and — as if you couldn’t guess the secret of being a good writer — he is a very good listener.

As we wait at the bar for a table, Terri, herself a good talker, zeroes in and starts chatting him up. Sitting in a Ukrainian restaurant in front of a plate of lard, Terri perhaps seemed a trifle ridiculous . Here in this glittering setting among Moscow’s beautiful people, everything about her suddenly makes perfect sense. This is her natural habitat. Not that Jane or I or Julia don’t like Cafe Pushkin. We can swim in these waters, too; we’re all good swimmers. But I for one prefer Cafe Babai. Interestingly enough, John from Bloomberg when we told him that we were coming here didn’t think of it as the best place in Moscow — sort of like the Tavern on the Green in Manhattan. “Definitely you have to go once if you haven’t been there, but there are probably a lot of better places if what you want is good food.”

As we wait at the bar for a table, Terri, herself a good talker, zeroes in and starts chatting him up. Sitting in a Ukrainian restaurant in front of a plate of lard, Terri perhaps seemed a trifle ridiculous . Here in this glittering setting among Moscow’s beautiful people, everything about her suddenly makes perfect sense. This is her natural habitat. Not that Jane or I or Julia don’t like Cafe Pushkin. We can swim in these waters, too; we’re all good swimmers. But I for one prefer Cafe Babai. Interestingly enough, John from Bloomberg when we told him that we were coming here didn’t think of it as the best place in Moscow — sort of like the Tavern on the Green in Manhattan. “Definitely you have to go once if you haven’t been there, but there are probably a lot of better places if what you want is good food.”

Terri, though, could probably eat here every night. She warns me to take some caviar fast, or she’s going to appropriate it all (how could we come to Moscow and not have caviar? And who better to share it with than John?).

I let Julia help me select an entree as usual, but it would be hard to make a real mistake. The food, needless to say, is rather rich.

It is nearing one thirty in the morning when we finally finish dinner. Marat is waiting outside, all dressed up from seeing his aunt, and happy to see us. We offer John a lift, but he prefers to walk. We had been told that Moscow was a dangerous city, but I guess it’s like New York — any of us wouldn’t be afraid to walk around at night in New York. We live there. We know where to go and where not to go.

As we drop Terri off at the Savoy, she announces that she has changed her plane reservation and is leaving tomorrow morning, not Sunday as planned. She wants to have a day to decompress in New York before going back to work. Terri and Julia had made plans to go to a design fair elsewhere in the city tomorrow morning, but I guess that’s out now. Jane was anticipating another happy day of butting heads (at one point Jane announces that if Terri rolls her eyes one more time, she’s going to get throttled). But Terri is Terri; she’s sampled all she needs to sample in Moscow and is ready to move on. Marat agrees to pick her up tomorrow at 6:30 a.m., even though he won’t get home tonight until very late indeed — what a mensch.

An instant later Terri waves goodbye and disappears into the grand lobby of her hotel. Our time together is over. Funny, I think we might actually miss her.

Mathes Missive from Moscow #12 – Saturday: Saturday Night Special

Hello, Tovarich (I actually used this expression on a Russian, who gave me a totally blank look, so either my pronunciation is off, he doesn’t watch American movies and know that this is supposed to mean comrade in Russian, or it’s politically incorrect to be a comrade nowadays– hey, do you think he just didn’t want to be my friend?),

This morning begins with the breakfast buffet at the Sheraton Palace, which the hotel manager has kindly comped us with over the weekend. Just what I needed — more food. At this point I’m beyond ready to get back to my dry seven-grain toast and tea at 3 Guys, the coffee shop up the street from our gallery in New York. But, hey, it’s a trip of a lifetime, what are you going to do? What I end up doing is freshly squeezed orange juice (such oranges!), coffee, fruit, bread, boiled buckwheat (had to try it, wasn’t bad), a red caviar blini, a made-to-order ham omelet (such eggs!), some herring, a piece of eel, several helpings of smoked salmon — some of the best I’ve ever tasted — and a sampling of smoked mackerel, which I generally don’t even like, but this was so terrific that I was ready to take as many pieces as I could fit into my pockets over to the Manege for lunch.

Back to healthy eating next week, Arlene, I promise.

We get to the Manege twenty minutes before the 2:00 opening time, so Julia and I set off on foot toward the Kremlin. The Kremlin is literally across the street from the Manege, and I know it would be crazy not to see at least a little of it while we are here. Jane doesn’t have the energy to join us, which is just as well because Julia’s fast pace would have killed her.

“Because of my Tatar heritage, I would have dragged your body back,” Julia later tells her, reassuringly. “By the heels.”

There is some kind of concert/promenade of ex-boarder guards, however, and all the entrances from Red Square to the walled in area of the Kremlin are closed (Julia finds it hysterical that I used to think that they called it Red Square because it was Communist; in fact it literally is red — the buildings are made of red bricks). So instead, we proceed at a brisk clip through the department store, GUM (as opposed to ZUM, across the street). At least I think this one is GUM. Whichever one it is, it turns out to be a va st, beautiful arcade complex filled with elegant boutiques and shops.

st, beautiful arcade complex filled with elegant boutiques and shops.

“Was this here during Soviet times?” I ask Julia, remembering all those tales of the deprived and starving people of the USSR that I heard growing up in the American Midwest during the height of the Cold War.

“Of course,” replies Julia. “One of my friends used to say that the difference between Americans and Russians was that you actually believed your government’s propaganda. We knew better. We were laughing our ears off at you.”

Thereafter ensued another day at the Moscow World Fine Art Fair, though anything that may have happened must remain a secret.

But complaints, by their very nature, are never secret, so here are a few choice ones for your enjoyment. You’d think that there’d be some place to get a quick bite at an event like this, in case a dealer didn’t want to leave his booth for two hours to go up to the elegant restaurant on the third floor for a three course lunch. Luckily there is: the small cafe next to our own booth, where you can wait half an hour for a table so you can have pastry and coffee — not the ideal lunch at 5:00 p.m. after you haven’t eaten anything since the two pounds of fish at 8:30 in the morning. Want a three-inch-tall bottle of Evian? That will be the equivalent of $6, please, if they haven ‘t run out. Too bad there is literally no other place in the entire building to get a drink of water (and remember, you can’t drink from the tap). When I said I was thinking of putting some mackerel in my pockets, I hope you understood that I was thinking SERIOUSLY.

And now that you begin to see behind the curtain some of the little difficulties that we art dealers must suffer, allow me to mention that there are also no wastebaskets at the Manege. Where are you supposed to put the wrappings if you can persuade a hedge fund person from New York like Terri to bring you sandwiches or strawberries from GUM (or ZUM)? I’m afraid your only option is to take the trash down to the men’s room and hope one of the ubiquitous cleaning girls spirits it away on one of her every-other-minute circuits of the urinals (don’t ask). It’s come to the point where I have begun eyeing our big Picasso ceramic bird as a possible garbage receptacle (hey, maybe we could suggest that it’s authentic Picasso garbage and raise the price)!

At the end of another day of meeting interesting people, we were about to depart for dinner when Julia noticed doings in the booth next door, that of perhaps the biggest figure in the arts in Russia, Zurab Tsereteli — painter, sculptor, architect and President of the Russian Academy of Arts. Tsereteli’s fame is international. His sculpture, “To the Struggle Against World Terrorism” — a 40 foot teardrop suspended in the fissure of a 106-foot bronze rectangular tower was recently installed in Bayonne, New Jersey. Bill Clinton, Homeland Security Chief Michael Chertoff and Governor Jon Corzine of New Jersey (one of three governors I’ve seen breakfasting at 3 Guys over the past year) all spoke at the dedication. Tsereteli’s fame is such that even Olga, the Russian diplomat whom I sat next to on the airplane coming over to Moscow, actually mentioned this sculpture to me with something like — but not exactly — admiration (“We call it the ‘Crying Vagina'”).

Though Tsereteli is ringed by a large entourage, Julia somehow manages to drag Jane over and get the great man’s attention. The next thing I know, Jane has led him to our booth and is showing him our wonderful Chagall tapestry, “La Vie.” I’m only sorry I couldn’t get a shot of everyone with the tapestry in the background, but that’s where the film crews were standing with their  cameras.

cameras.

The fellow on the left, by the way, is the world-weary Russian artist who told us the other night that a taxi from the Manege to the hotel should be about 200 Rubles. I don’t know his name but his work is being shown at the fair by an important French gallery. Everybody knows Tsereteli, and Tsereteli knows everybody that matters. Now Tsereteli knows us.

Marat has suggested that we dine tonight at a traditional Russian restaurant on Arbot Street that is big with politicians and the Russian mafia (a quality predictor that had proved quite accurate with Sun of the Desert) but we passed the place the other day in the rain and know that it’s closed. Julia decides that our best bet will be Godunov, another traditional Russian place with two advantages — it is close by so we can walk and see a little of the Kremlin after all. And it is supposed to have gypsy dancing, which Julia knows we enjoy so much.

How do you like this for a nice little walk over to dinner?

That’s St. Basil’s Cathedral behind us in most of the shots, by the way. The long red wall is the Kremlin. The guy in the last shot offered to take pictures of the three of us. We very much would have liked to have such photos, but I thought it might be wiser for tourists not to give their cameras to a strange character in Red Square channeling Elvis.

That’s St. Basil’s Cathedral behind us in most of the shots, by the way. The long red wall is the Kremlin. The guy in the last shot offered to take pictures of the three of us. We very much would have liked to have such photos, but I thought it might be wiser for tourists not to give their cameras to a strange character in Red Square channeling Elvis.

“I prefer to think the best of my countrymen,” said Julia, but who nevertheless agreed.

Alas, no Gypsies appeared at Godunov, but the food was terrific, classic old Russia. Though the bear and moose dishes sounded delightful, I wanted to try something Russian that I’d had before so I could have some point of comparison. The Beef Stroganoff at Godunov’s came in its own loaf of brown bread and was significant better than the one my girlfriend made for me in 1966. Sorry, Rosie. The fish pie (pike, sturgeon and salmon) took 20 minutes to bake and we couldn’t finish it (Julia will take it home and keep it for lunch tomorrow), but it was delicious. And you can’t imagine what sour cream really tastes like unless you can taste it here.

Do you get that we are foodies?

Do you get that we are foodies?

It was actually before midnight for a change when we left the restaurant. Marat was waiting with his car across the square outside. He was very impressed with our restaurant choice — it turns out that Godunov’s is even more popular with politicians and the Russian mafia than Marat’s initial suggestion.

Yes, definitely back to vegetables next week.

Julia made me pose this way, I swear

Julia made me pose this way, I swear

Mathes Missive from Moscow #13 – Sunday: In Alexandrovsky Sad with Jane and Julia

Zdrastvuita (an approximation of how you say hello in Russian, according to Julia), from Moscow,

When I run into Jane this morning at the breakfast buffet she demands to know what I am going to take for lunch. You recall that yesterday I had been seriously eying the smoked mackerel, but I just don’t have the Jewish grandmother gene that enables one to load up and spirit away quantities of food from buffets. Jane has such a gene. Also, like all Jewish grandmothers, she travels with plastic bags specifically for this purpose (actually the purpose may also involve cleaning up after her two small dogs in  New York, but the point is that she is prepared for everything).

New York, but the point is that she is prepared for everything).

Under the stern gaze of the hotel staff (“they want you to take food with you,” insists Jane), I can’t bring myself to take more than a pear. Rolling her eyes in a manner that would make Terri proud, Jane spirits a croissant back to the table and slips it into a baggie.

“What else?” she whispers.

“Mackerel?”

Even Jane draws the line at this. Alas.

“Take that pear, Charles. At least take that pear.”

“Whatever,” I say, taking a line from Terri’s book. And the pear.

On the way over to the Manege this morning, we see a girl riding a horse down the sidewalk. Both appear sober. Nobody on the street seems particularly surprised — you can see how much Moscow is like New York in this respect. Jane once saw Mayor Koch leading an elephant up Broadway; nobody on the street blinked an eye. All kinds of animals walk our streets. Here, too, I guess.

Whereupon begins another day at the Art Fair, the details of which must remain secret (we do meet some interesting people).

I have to report that, fancy dinners every night notwithstanding, we are under a lot of pressure, pretty worn out and getting a little cranky. All three of us are strong individuals, have similar coughs (I apparently have infected Jane now, too) and are under a lot of pressure. And while many of the interesting people we are meeting are exactly like (and sometimes simply exactly) the cosmopolitan, sophisticated people we meet at art fairs in New York, Miami and Los Angeles, many Russians who have suddenly acquired and are ready to spend great wealth have no experience with the art world. We continually are asked if what we have brought is for sale, and when is our auction. A surprising number of people speak English or French (leaving Julia with less to do than she would prefer), but an equally surprising number will not even give their names; it’s difficult to know which situations will lead to results.

“If he’s such an oligarch,” says Jane after one such encounter, “why doesn’t he have any teeth?”

As a personal trainer in New York, Julia specializes in telling people what to do, getting her own way, and making grown men cry. Jane has the same specialties, which is perhaps why they get along so well. But several times over the past few days Julia has offered to be helpful beyond simple (as if it were simple) translation. She wonders if  Jane understands all the subtle nuances of cultural differences that present themselves in each encounter. Jane, who has been selling art since the 1960s, doesn’t really need advice on her sales approach at this point in life (especially in the middle of an art fair), and wonders if Julia understands the first thing about the realities and complexities of making sales at this level. Me, I’m wondering if they’re going to be serving food at the big party for exhibitors to which we’ve been invited tonight.

Jane understands all the subtle nuances of cultural differences that present themselves in each encounter. Jane, who has been selling art since the 1960s, doesn’t really need advice on her sales approach at this point in life (especially in the middle of an art fair), and wonders if Julia understands the first thing about the realities and complexities of making sales at this level. Me, I’m wondering if they’re going to be serving food at the big party for exhibitors to which we’ve been invited tonight.

At five o’clock my breakfast has finally worn off and I am a grateful for my pear and for the croissant that Jane has spirited from the buffet. One of Julia’s many friends who have come to visit us has brought a vegetable pie (hours ago Julia polished off the remains of the fish pie from Godunov’s) of which we also partake. Then Julia and Jane gang up on me for not making away with more from breakfast.

“Did you grow up rich and didn’t have to learn to forage for food?” they demand.

I blame it all on my mother, who kept reading me the same Aesop fable over and over when I was a little boy. The one about the man who, as he is being led to the gallows asks to be allowed to whisper into his mother’s ear. Instead, he bites it off. “Why?” she cries.

“Because when I was a little boy and I stole that first piece of smoked mackerel,” he says — as I recall it, “you didn’t punish me, and so soon I was stealing horses, then knocking over banks, and finally murder, which has brought me to where I am today!”

I think I was about 45 years old before my little mother for the first time dared to start believing that I wouldn’t end up on the gallows. She still will not let me whisper into her ear.

So is it any surprise that I am horrified when Julia now says that since fish is smoked to preserve it, this is something we should perhaps take away in little baggies tomorrow, besides more fruit, rolls and pastry (for all I know she is thinking about the silverware, too). Who knew that Julia would have the Jewish grandmother gene!

At nine o’clock the fair ends for the night, and we proceed to the minibuses that the Fair organizers have arranged to take us to the Exhibitors party at the prestigious Central Writers House, which I gather was some kind of exclusive private club for people like Nabakov during Soviet times and is still one of the fanciest venues in the city. Julia knows we will be particularly happy that there will be gypsy musicians and dancers tonight. (It is always best to hire gypsy musicians for gypsy dancers, Julia says, proudly telling a story she heard about how when regular musicians took a break, the gypsy dancers opened the door to the back alley and sold their instruments).

At nine o’clock the fair ends for the night, and we proceed to the minibuses that the Fair organizers have arranged to take us to the Exhibitors party at the prestigious Central Writers House, which I gather was some kind of exclusive private club for people like Nabakov during Soviet times and is still one of the fanciest venues in the city. Julia knows we will be particularly happy that there will be gypsy musicians and dancers tonight. (It is always best to hire gypsy musicians for gypsy dancers, Julia says, proudly telling a story she heard about how when regular musicians took a break, the gypsy dancers opened the door to the back alley and sold their instruments).

Central Writers House turns out to be a spectacular multi-level palace, all wood-paneled, and complete with towering stained glass windows. There are lavish buffets of food everywhere, wine, women and song. Now we know another reason why the booth costs are astronomical; this bash is going to cost somebody a fortune, and that somebody is us! The din is incredible. The only places to sit are upstairs, which doubles as a cigar lounge (which like the premium scotches, the vodka and the gallons of Cognac are distributed freely). People crush happily into one another. As Jane later described the scene: “There was food but you couldn’t reach it. There was dancing but you couldn’t see it. There was air, but you couldn’t breathe it.”

Central Writers House turns out to be a spectacular multi-level palace, all wood-paneled, and complete with towering stained glass windows. There are lavish buffets of food everywhere, wine, women and song. Now we know another reason why the booth costs are astronomical; this bash is going to cost somebody a fortune, and that somebody is us! The din is incredible. The only places to sit are upstairs, which doubles as a cigar lounge (which like the premium scotches, the vodka and the gallons of Cognac are distributed freely). People crush happily into one another. As Jane later described the scene: “There was food but you couldn’t reach it. There was dancing but you couldn’t see it. There was air, but you couldn’t breathe it.”

Actually she did reach the food and went on and on about how marvelous the crabcakes were. They were chicken. You lose some of your sense of taste when you have a cold.

We’re always being pestered by artists who somehow think that even though our gallery is limited to handling people like Picasso and Chagall, what we really want to do is represent them, too. This is the first time I was ever so pestered by woman artist who was smoking a cigar. Apparently she had interpreted William Shakespeare sonnets in lithography and wanted to know what I thought.

I recited “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” (my father would be pleased that my M.F.A. in Theatre has finally come in so handy) and escaped into the crowd as she chewed her cigar, trying to figure out what the hell I had said. Even Julia couldn’t translate!

Somewhere around midnight Jane runs into William, the charming young Frenchman who was so helpful to Jane in Paris when we learned that the deadline for shipping all of our art to Geneva was not April 15 as we had been told all along, but March 15 (it was then the first week of March). Thanks to William, whom Jane always describes as wonderful and helpful, she was able to spend two days furious designing the booth from wrong dimensions, order all the lighting fixtures (every one of which Nicola had to replace the night before the opening), and it was William who presented the bill for the lights on Friday, payable Monday (this morning he showed up and said our credit card had expired — luckily Jane had it, unexpired, in her backpack).

Now William tells her that tomorrow, Monday night, after the fair ends, we will not be allowed to move out as planned. No, the move-out can only commence on Tuesday.

Now William tells her that tomorrow, Monday night, after the fair ends, we will not be allowed to move out as planned. No, the move-out can only commence on Tuesday.

To give you some perspective on what this little piece of eleventh (twelfth, actually) hour information means, here’s what usually happens during a fair move-out. I’ve been doing these with Jane since 1994 at dozens of fairs in New York City, in Miami, in Los Angeles, in Seattle and other places. When the doors are closed for the last time to the public, work crews which have been assembling for the past few hours descend and start removing the art from the walls. Each piece must be checked off on a disposition list, packed up for transit, taken out to a waiting truck, and then checked again against the list to make sure that everything that left the hall made it onto the truck. Sometimes our registrar or another person on our staff checks the items against the disposition list, while a team of hired art handlers packs each piece up. Other times our hired art handlers take responsibility for all the checking, too. Usually a fair closes no later than seven o’clock on the last night. Depending on unpredictables — especially in union venues — the truck can be loaded and on the road as early as ten o’clock or as late as five or six the next morning (don’t expect a lot of sleep if you are doing any fairs at the Javits Convention Center in New York).

Over all the past months nobody at the fair has been able to tell us exactly what to expect during the move-out, despite our asking numerous times. In our planning we have tried to cover all possible situations. While we didn’t know whether it would be the French or Russian handlers who would be helping us pack, we had to assume that they would be as good as their American counterparts. Jane speaks French and Julia speaks Russian, so we will be able to tell them exactly what to do.

It is the handlers who actually do most (or, even all, as I said) the work, so our participation will be limited to checking the works against the disposition lists and making sure that nothing is left behind. The fair doesn’t conclude until 9:00 pm, so we know that it’s going to be a late night. To save an extra night in the hotel, I am checking out and flying back to New York on Tuesday. I can work all night if necessary, but I know that Jane will probably not want to stay too much past midnight. With any luck we will have a good grip on things by then, and either the handlers can finish up on Tuesday morning, some time between 1:00 am and 5:00 pm. Jane isn’t leaving until Wednesday, so she can instruct handlers in French if necessary all Tuesday. We’ve been told that the Russian handlers are not as good as the French (I’m hoping these are not the same guys who refused to hammer a nail into a wall, but Julia, Jane and I can take the paintings off the walls if necessary), so Julia is staying until Thursday, so that she can wrap things up in Russian if it comes to that.

Because we are in a strange country (make that ‘Strange’), international customs are involved, and shipping is more complex since crates are requir ed. We know things will be more complicated, but we have great confidence that everything will be okay. Make that ‘had great confidence.’ If nothing is going to start until Tuesday when I am already gone, will there be enough time for Jane to finish everything before she leaves. And how many other galleries are the French handlers handling? Are they going to keep us waiting until dinnertime? (It could happen, I suppose, but Jane will probably drag them over by their heels long before then.) At least we have established a nice relationship with Natalia, the customs person who with Jane checked each piece as it was uncrated against the shipped items list. We gave her passes to the show and she seemed very impressed.

ed. We know things will be more complicated, but we have great confidence that everything will be okay. Make that ‘had great confidence.’ If nothing is going to start until Tuesday when I am already gone, will there be enough time for Jane to finish everything before she leaves. And how many other galleries are the French handlers handling? Are they going to keep us waiting until dinnertime? (It could happen, I suppose, but Jane will probably drag them over by their heels long before then.) At least we have established a nice relationship with Natalia, the customs person who with Jane checked each piece as it was uncrated against the shipped items list. We gave her passes to the show and she seemed very impressed.

We run into Oxana, the marvelous efficient manager of the Russian team, and ask what the move-out will be like.

“Chaos, I think,” she says happily.

What was it like last year?

“Chaos.”

I have made friends with a big bear of a Russian, whom I think I will call Ivan the Terrible. It’s just like in the movies — we collide at the bar and both try to get a vodka, then defer to the other. You, first, Alphonse. No, you, Gaston. Of course, he speaks no English. When we have both gotten our little glasses, we click, and drink – Tovarish (he’s actually the one who gives me the blank look at this expression)! Here’s to Vodka, the universal communication.

With Jane suitably dazed by her talk with William, hacking from cigar smoke and Charles’s cold, and stuffed to the gills with every fancy food imaginable that has been served throughout the night on the dark buffet tables against the backdrop of wall-to-wall intoxicated art dealers and gypsy music, I introduce her to Ivan the Terrible, who has found out that I have had only two tiny glasses of vodka to his four, so has brought me a tumblerful (well, not a tumbler, but certainly a bigger glass).

It turns out (now that Julia is corralled to translate), Ivan is a journalist. Hard to understand what else he was saying, even translated into English. He did kiss Jane’s hand several times and say he would come by the Manege tomorrow. If he does, I think she may kill me for making the introduction.

We get back to the hotel at 1:30 in the morning. A dandy time was had by all.

Mathes Missive from Moscow #14 – Monday: The Last Day, The Last Missive

Greetings for the final time from Moscow,

Today, Monday, is the last day of the Moscow World Fine Art Fair. Fairs tend to end with whimpers rather than build to crescendos. While it’s possible that multiple oligarchs will descend upon the booth in the last five minutes with sacks of rubles on their shoulders, the majority of dealers at most fairs sell nothing. The odds of selling in Russia are supposed to be even longer. Numerous old-timers have told us nothing will happen until the Russians begin to know and trust us — which will take years. These same people have also marveled at a foreigner who came to Moscow a few years ago and miraculously left with one of the richest men in Russia as her devoted client. (What they don’t know is that the oligarch discovered that the woman was in fact his long-lost cousin — so much for miracles.)

In any event, I would like to tell you that we are optimists at heart — but I cannot, since this information would be confidential.

But the omens do not bode well. The first thing I see when I look out my hotel window this morning are three unloved, unwanted stray dogs sleeping in the construction site across the street. Lucky I’m not Herman Melville; any symbolic comparison to Jane, Julia and me is strictly coincidental. I hope. It is also about to rain, which doesn’t thrill me — I have turned in my borrowed umbrella to the Sheraton. Even the breakfast buffet has lost its allure. How much fish does a person really want to eat at 8:00 o’clock? And instead of fresh squeezed orange juice this morning, I get canned. Definitely not a good sign if you’re superstitious (luckily I’m not, knock on wood).

Surprisingly, it is a busy day at the fair. Last days are often sparsely attended, but here the crowds still pack the aisles. Crowds, however, mean nothing. There is probably only one real buyer for every thousand browsers at events like these. Most folks view art fairs the way they do museums, sporting events, and zoos: as entertainment. I suppose things equal out, since we have to view the people who wander through as prey. We are fishermen. But catching a bunch of small fry will not begin to pay our expenses. Like every dealer here, we have brought only our best and most expensive items as bait. We are fishing for whales. All we need to catch is one.

The day proceeds as days at any art fair do. Secretly. At five o’clock wry, beautiful Oxana (have I mentioned how beautiful Russian women are?) drops by the booth to inquire if we have made arrangements for the move-out. We told her what William told us last night, that nothing would happen until Tuesday. “Sorry,” says Oxana cheerfully (chaos makes her cheerful), “not true.”

Determined to figure out what’s going on, Jane tracks down sober, stern-looking Francoise (Swiss, you know), whom everyone says is in charge of the move-out (William, Oxana, and Francoise all belong to different groups identified by different letter arrangements: SOC, ACS, CIA, AT&T). Francoise has yet a third version of tonight’s events — totally different than either of the other’s (except the bit about the chaos).

Determined to figure out what’s going on, Jane tracks down sober, stern-looking Francoise (Swiss, you know), whom everyone says is in charge of the move-out (William, Oxana, and Francoise all belong to different groups identified by different letter arrangements: SOC, ACS, CIA, AT&T). Francoise has yet a third version of tonight’s events — totally different than either of the other’s (except the bit about the chaos).

At nine o’clock the guards usher the stragglers and last-minute hagglers out of the Manege. The house lights go on. Crates start appearing in the aisles. The fair is over.

How did we do? Unfortunately, you know I cannot tell you — even if we knew ourselves at this point (whether we do or not I can’t say, either). But you are welcome to assume the best, or the worst, depending upon your philosophical orientation in life.

As we pack up the materials that we carried into Russia and will carry out in our hand luggage, we finally understand that 1) we don’t have any choice but to trust the wonderful (and expensive) French art handlers (who are actually Swiss) to pack up our booth; 2) customs will come tonight, but they don’t need for us to be present to verify that everything that came out of the crates will go back into the crates — checking paperwork is their passion; 3) SERIOUS guards are everywhere throughout the building so nothing will disappear; 4) every crate will be weighed after it is packed and all discrepancies will be investigated; 5) we are paying a fortune for insurance and are covered if anything does happen to go wrong. So why do we want to stick around all night?

There really is only one sensible thing for us to do.

Marat and our magic carpet are waiting outside the Manege. It is quarter to eleven when we arrive at Cafe Babai; our favorite neighborhood Uzbek restaurant is open until midnight. The three of us share a last meal together (don’t miss the Wedding Plov, is my advice to you) and compare notes. At quarter to one we are still comparing, but the gracious Uzbeks apparently never even consider throwing us out — everyone we have encountered in this city is hospitable and gracious.

Jane has a full-blown cold, a sore throat (hey, I never had a sore throat — maybe what she has isn’t mine), and a slight fever, which she plans to enjoy over the following week. Tomorrow she will sleep late, then come back to Manege and check to see what happened last night. Was our booth properly disassembled? Did everything make it intact into the crates? Will we have problems with customs? Jane wants to believe everything will have been done perfectly (if it isn’t, look out below). On Wednesday she will fly to Switzerland — Art Basel, one of the most important art fairs in the world, is opening this week. Jane never misses it — not to exhibit, God forbid, but just to keep up on what’s going on. (Some would say that she is a tireless, dedicated, passionate art professional to run off to Basel after just spending two weeks working her tail off in Moscow; others would say there is perhaps just the teeniest bit of lunacy involved.)

Julia has decided not to go to Greece after all. The paper she was to deliver on Gypsy dance was due on May 31st. Julia had been staying up all night working on it at her friend’s unheated apartment at the beginning of the week, after frog-marching us through Moscow every day through the rain. This is why she got sick, she claims again, it wasn’t from me at all. With the paper unfinished and the trip to Greece unnecessary, Julia can now spend two weeks doing what she says will certainly cure her — swim in the Black Sea. It may be that she actually intends to swim ACROSS the Black Sea. If anyone can do this, it would be Julia. She must return to her friend’s cold apartment again tonight — there are no rooms available at the hotel. When I realize she doesn’t have any warm clothes, I lend her my sweater — I won’t need it, I’m going back to New York tomorrow.

Julia is still puzzling what she will do with the rest of her life. Over the past few days she has made several comments about how she believes she could be very effective in the art business, and that maybe she might have a gallery of her own one day. A lot easier said than done, but if someone can swim the Black Sea, maybe she could also make a success in the art business. The tasks are probably on a par.

As for myself, tomorrow Marat will pick me up at the Sheraton Palace at 8:00 a.m. and drive me to the airport. He has to charge 500 rubles more than he charged Terry because the traffic as he returns to the center city will take hours to negotiate on a weekday morning.

As for myself, tomorrow Marat will pick me up at the Sheraton Palace at 8:00 a.m. and drive me to the airport. He has to charge 500 rubles more than he charged Terry because the traffic as he returns to the center city will take hours to negotiate on a weekday morning.

“Stalin built roads, Brezhnev built roads,” he will tell me (with hands and “mouths”) during the drive. “Roads are what the people need – there is only this one road to the airport and it must bear all the traffic. Is it any wonder it’s so crowded? But Medvedev and Putin, all they build are more and more big buildings downtown, because that is where the money is . How’s your cough ?”

“Better, thanks. I gave it to Jane (‘Mouth’).”

“May God watch over you and give you a safe flight home,” says Marat at the airport as he helps me wheel my two suitcases to the curb. Actually he just points at the miniature reproductions of icons on his dashboard (the Armenian equivalent of fuzzy dice?), then holds his hand to his heart, then points to me. “You will call me when you come back, and I will be here to drive you again, yes?”

“Absolutely! ” I assure him (“Absolutely!”). We share a manly hug and pound one another on the back.

In the Moscow Times on Monday I will read about how bands of skinheads have been assaulting Jews and Armenians and anybody who isn’t an ethnic Russian. I know there is a dark side to Russia, and I am glad that I did not see it. I saw only happy, brilliant, playful, funny, likeable, gracious people. There is a dark side of America, too. I don’t want to see it, either.

On the nine and a half hour flight back to New York as I will write this last missive, I will look back over my time in Russia with Jane and Julia, with Terri, with Marat, with John from Bloomberg and marvel at my good fortune. It has indeed been a trip of a lifetime for us all.

I suppose I should be tired after two weeks of working from morning to night, eating too much too late, straining each minute of each day to do everything I can to maximize our chances of making a sale. To a gallery sales are survival. There has been not just a lot at stake here, there has been everything. But I’m not tired. In fact I’m invigorated and looking forward to the future, as in their own ways are all the characters in this little play, I’m sure.

My thoughts keep coming back to something Julia said a few days ago.

“The best rest is the change of activity.”

Julia had been quoting Lenin. Somehow that’s both fitting and accurate, I think. I do feel rested. And changed. And happy that I’ve been able to bring you along.

Do svidaniya! from Moscow. See you in New York.

P.S. By my count (and I’m counting this back in New York after after about 15 hours in transit, so I might be mistaken) there have been 15 Missives from Moscow (counting #6 1/2). If you didn’t receive one, please let me know and I’ll resend. When I wake up.

I Hate Cozies!

Like many mystery readers, what I like best in the whole world is to curl up in a comfy chair in front a fireplace with a book in which I can lose myself for hours and hours; a book that is fast-paced and fun, full of odd characters and unexpected events; a book that challenges me and takes me to places that I might not dare go in real life, but doesn’t leave me afterwards wanting to stick my head in an oven or feeling like I need a shower.

If you had to come up with one word that captured the essence of this kind of book, what would it be? Perhaps “cozy” might fit the bill, but to many publishers and booksellers the word “cozy” connotes a mystery filled with cats and little old ladies drinking tea. It also says “this kind of book has a very small audience.”

I was a panelist recently at an MWA event in New York where I live, and a member of the audience, apologizing for her naiveté, asked the question. “What is a cozy?”

The True Crime lady was happy to pipe up with something to the effect of “Oh, that’s where you have an amateur detective and she — it’s practically always a she — has some neighbor murdered and she takes it upon herself to INVESTIGATE because the police are always incredibly stupid and there’s no violence, but there are always lots of cats, and everyone sits around and drinks tea.”

Who the hell would want to read such a thing? Or write such a thing? Even Agatha Christie, who probably is the prototypical cozy author, never did.

The fact is that all of us, authors, editors and readers alike, are prisoners of mystery categories. And if it’s not a Private Detective, a Police Procedural, a Historical or a Noir, increasingly often it’s being lumped into the Cozy bin. I’ve seen everyone from Lawrence Block to Sujata Massey referred to as “cozies” and this is just crazy. The cozy catch-all is like the bed of Procrustes, a bandit of Greek myth who invited his victims to have a lie down. If they were too big to fit on the bed, he cut off their feet. If they were too short, he stretched them.

Naturally publishers and booksellers need some kind of categories in order to steer customers to the kind of books they might like. “Mystery” itself is a category. However, the deck is getting stacked against the sub-genre of cozies. It doesn’t matter if a writer has never included a cat or a cup of tea in his books (and I have nothing against cats or tea, believe me). The problem is that once he’s lumped into the Cozy category he’s increasingly likely to have his contract cancelled because publishers think “cozies” aren’t profitable — or worse, that they’re not important and macho enough for their big important house.

IF NOT COZIES, THEN WHAT?

I’ve made the case for the term “Maverick” — at least for my own work, which doesn’t really fit any of the current terminology. However, the real categories of all books, mysteries included, are still the ones I learned when I was studying playwriting: comedy, tragedy, melodrama and farce. Within these categories I — and every other writer — fits nicely. I happen to write comedy — not the funny, ha-ha kind, but the form in which the ground falls out from under you at the end and plunges the level of discourse in a celebration of life. I recognize that some mysteries are crafted as tragedies, and some as farce, but the vast majority today are simply melodramas.

Aristotle identified various elements that a good story has to have. You could go from the lowest — spectacle — up through words and music, to plot, then to character, and finally to thought. The vast majorities of mysteries today do not fit into any of these areas. They are, plain and simple, melodramas, the form that has always been the most popular with the masses. There is no catharsis of pity and fear here, and no celebration when order returns (as it does in comedy) from chaos. There is simply a thrill a minute. Pauline is tied to the railroad tracks. We gasp. She’s saved at the last minute. We breathe a sigh of relief. But then the villain carries her off again. The curve of the action takes place not in the story or the thought, but in the audience’s emotions.

Serial killer books are the logical conclusion of this form, a genre which is entirely about eliciting strong emotions in the reader. It is the addicts of this emotional fix — and of course the horror that is encountered has to be ratcheted up in each book until you have children being skinned alive and other excesses worthy of the end of the Roman Empire, which is where the genre is today in my opinion — it is these people who have invented the word “cozy” and made it a pejorative term. Who could possibly care about some little old lady solving crimes and drinking tea when there are children being abused, women being raped, good men being killed in the most horrible fashion imaginable ( — all in the name of selling books)?

The fact is, however, that redemption and the return of the moral center is more likely to come from a well-crafted classical comedy with integrity than from the final, last minute destruction of the most hideous serial killer imaginable. That’s why Classical Comedy is what I try to write. But try selling it as that!

Where to eat in Chinatown

My mystery novel, The Girl at the End of the Line, features a jaunt through New York City’s Chinatown and a dim sum lunch.

If, like Molly and Nell O’Hara, you’ve never experienced such a repast you’re in for a treat. There are plenty of places to try if you fin

d yourself in the Big Apple, but the restaurant in my book was loosely based on Jing Fong on 20 Elizabeth Street between Bayard and Canal.

Okay, it doesn’t look like much from the outside — in fact it looks distinctly forbidding, plus you have to ascend a daunting escalator. But inside on the second floor you will be rewarded with one of the largest and most exotic restaurants in New York.

A lot of sites

will give you eight million choices of where to eat, but if you’re like me this is no help. I don’t want someone to give me options. I want advice. So here’s my advice to you: if you want to eat one meal in Chinatown and don’t want a weird exotic location like Jing Fong with weird and exotic food (some dim sum is distinctly strange for a Western palate), if you just want some great and surprisingly inexpensive Chinese food, I say GREAT NEW YORK NOODLETOWN at 28 1/2 Bowery at Bayard Street. The ambiance is zero but the food is incredible. Try the salt-baked combo (or if you don’t like squid and scallops, go for just the salt baked shrimp). The duck with asparagus is out of this world. And if you don’t believe me that this is the best joint in Chinatown, even Zagat and Martha Stewart sing this place’s praises.

My New York by Charles Mathes

I’m the author of a series of stand-alone mysteries, each featuring a different young woman with a problem in her past. A hotel-inspector orphan searching for her family. The professional magician desperate to understand why her grandfather was murdered. A pair of antique-dealer sisters whose grandmother sank into poverty after a Broadway career. A professional stage fight director whose father lies in a coma.

The books appear to be connected only by the word “Girl” in the title, but in fact each novel includes the same pivotal character with whom all of my heroines interact. The character’s name is New York City. Like any pivotal character my New York is a catalyst that forces my heroines to change, to grow, to develop.

Perhaps this is because New York forced me to change. Everyone who comes to the City to forge a career has to put aside old concepts of how things are supposed to work and reinvent him or herself to survive in a town that is both without limits and without mercy.

The stereotype is that you have to move fast here or you’ll get trampled, talk fast or you won’t get in a word edgewise and think fast or you’ll be left without the shirt on your back or a penny to your name.

The reality is that the city lets you be anything you want to be (which is probably why so many misfits end up here), but always makes you keep things in perspective. It’s hard to think you’re such a big deal when buildings soar sixty stories on every corner, but it’s hard not to feel like a king or queen when you’re walking down Fifth Avenue and the sun is shining and the city is pulsating with the energy of a million people certain that they are in the nexus of the world.

Like most “real” New Yorkers I was born out of town – Cleveland, Ohio, to be exact. My first taste of the Big Apple came on a family vacation when I was just a kid. I was used to the suburbs and had never seen anything like Manhattan before. Our hotel was something out of a movie, as bustling and gigantic as an airport, full of little shops and high ceilings and bellboys running around in red uniforms. A cab took us to a nondescript building on a seemingly deserted street. We opened the door and found ourselves in a cavernous restaurant full of beautifully dressed sophisticates. I ordered Lobster Thermador and nobody batted an eye.

When we came out of a movie theatre on Broadway at eleven o’clock at night the streets were more crowded with people than downtown Cleveland was at rush hour. And such people! Ladies with faces thick with make-up and cynicism smiling out from dark corners at passersby; guys with sharkskin suits and pug noses lighting up Parliaments with gold cigarette lighters; a leathery old broad dressed like a fireworks display and bellowing to herself about how the Commies had taken over the government.

My father, the traveling salesman, told me that if you waited around long enough in Times Square, you would eventually run into everyone you had ever met. I gave a skeptical glance around and to my astonishment was hailed by a kid I recognized from summer camp in Indiana the summer before. I was hooked. New York was pure magic, a place of miracles!

In high school I found myself in the City again, this time with my high school choir. Carefully chaperoned, my friends and I did the usual tourist things – saw the show at Radio City Music Hall, went to the top of the Empire State Building, checked out the U.N. Then we went up to Harlem and sang a concert in the chapel of the Salvation Army and saw a different New York City, a city where tourists never went but one that just as alive and full of heart as anything downtown. I felt welcome and safe and happy. New York was an old friend.

As a college freshman I came back to New York by myself. Confident that I would have another great time, I checked into a “reasonably priced” hotel in midtown. The room was tiny and dark. Sirens wailed in filthy streets far below. I walked through Times Square again, this time without my friends or my family. I didn’t recognize a soul. Thousands of people rushed by, none of them caring whether I lived or died. I ate alone in a greasy diner, the only place I could afford, and was hustled out when they wanted the table for a larger party. The city was overwhelming, gigantic and anonymous. I never had felt so lonely in my life.

After that I had no desire to go back. Each time I thought about New York, it grew bigger and uglier and more dangerous in mind. It was the seventies. Johnny Carson assured us that if we ventured into Central Park we would get killed. Kitty Genovese’s screams didn’t bother the neighbors. Every subway car pictured in the movies was a graffiti-scribbled horror. New York was a gigantic back alley that ate up idealistic young people and spit them out, where cops answered domestic disturbance calls and got shot in face. New York was Hell.

Yet every Sunday through all the time I was in college, I would sit in a restaurant in St. Louis or Pittsburgh and read the New York Times. I wanted to be in the arts, and there was no getting away from the fact that if I wanted a “real” career, I would one day have to come back to New York. That’s just the way the country is set up. New York is the focal point, the main stage, the major leagues. Sure you could have a nice career as a “local” artist or actor or writer or musician, but you would never be in the same category as those folks who had made it in New York.

It isn’t fair, of course, but it’s true. New York is like the sun. The other cities in America – and increasingly the world – are mere planets, trapped for better or for worse in New York’s gravity, illuminated by its brilliance. This I think is why people outside of New York tend to see the city, either in memory or in imagination, as some kind of huge monolithic menace. They speak of New York this, New York that – as if the city really were a character, as if it had a mind and objectives of its own.

It doesn’t of course. It’s just a bunch of concrete and glass, steel and asphalt, flesh and blood. Its very mass and complexity, however, has the power to turn grown people into children when they see it for the first time, which I think is reason why my heroines all end up here at some point – not just because gravity pulls everyone here eventually, but because when a person sees New York for the first time, he or she invariably sees it as a child, with a child’s terrible sense of magic and wonder and awe. That’s what changes them. That’s what makes them grow. Frankly it’s something I want to experience again and again, something I want to share.

Eventually, of course, I came here to live. I had to. I sold my car and cashed in my stamp collection and made arrangements to stay with a friend I knew from college. All my bridges were burned. As my plane landed with LaGuardia I knew I had enough money to hold out for three months. If I couldn’t get a job in that time, I didn’t know what would become of me. I was scared to death.

As the taxi carried me and the three suitcases which held everything I owned in the world over the Triborough Bridge, the towers of the city suddenly flashed into sight, twinkling with sunlight and the dreams of million young people like me. It was majestic and awesome and magical. Gershwin seemed to well up out of nowhere, just like in a Woody Allen move.

Suddenly all the fear, bad memories and awful anticipation were gone. I was a child again. I knew I was home.

(This essay originally appeared in Mystery Scene Magazine)