What is an Appraisal and Who Needs It?

When people have a piece of art they want to sell they often think that their first step should be to get an “appraisal” so they won’t be taken advantage of.

But what is an appraisal? When your friend who owns an antique shop says, “This is worth about three thousand bucks,” is that an appraisal? How about when an imperious looking chap wearing a bespoke suit and a British accent looks at your painting on THE ANTIQUES ROADSHOW and declares that it would bring $40,000 – $50,000 at auction? Did you get an appraisal?

The dictionary might say both of these are examples of appraisals, but according to the Appraisal Foundation which was authorized by Congress as the source of appraisal standards and appraiser qualifications, to be credible an appraisal must conform to rules that the Appraisal Foundation refines and publishes every two years in a big fat book entitled the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP). USPAP compliant appraisal reports can run dozens of pages even for single paintings in order to conform to the standards. To jump through the required hoops takes a lot of hours on the part of the appraiser, so USPAP compliant appraisals are expensive propositions. USPAP says that even oral appraisals must conform to all the myriad standards and be documented in a work file, so it is unlikely that any oral appraisal is USPAP compliant. Members of the professional appraisal associations (the Appraisers Association of America, the American Society of Appraisers and the International Society of Appraisers) all REQUIRE their members to perform only USPAP compliant appraisals.

A person needs a pet grooming license in New York City to shampoo your poodle. To come into your house and do an “appraisal” of your silverware, he doesn’t even need a business card that identifies him as an appraiser. Anybody can give you an “appraisal.” For that matter anyone can issue a “Certificate of Authenticity” for your Picasso, which will be just as credible as the issuing party. The whole point of USPAP and appraisal organizations is to make sure that the public can have confidence in appraisals done by unbiased professionals experienced in the business of valuation – not the business of grooming poodles or selling your property to make themselves a profit.

Bottom line, a credible appraisal is usually a lengthy document conforming to USPAP standards written by a member of a professional appraisal group. If you’re dealing with the IRS for a charitable contribution or for estate tax purposes, chances are you need such a document. Your insurance company may also require it to protect your expensive art collection. Perhaps a credible appraisal is necessary in a court situation — a divorce or a lawsuit.

But if you just want to get some idea of what your art is worth so you can sell it, you very well may not need and probably shouldn’t have to pay for a professional, USPAP compliant appraisal report. So ask your dealer friend for his opinion, run it past an auction house if you like, but be aware that the oral “appraisal” you receive may not be worth the paper it’s written on.

Appraising Damaged Fine Art Ceramics

Picasso, Chagall, Miro, Leger, Matisse and other important 20th century artists created ceramic works. It could be a serious mistake for appraisers to use the same percentages to assess loss of value to such fine art pieces as some have suggested for damaged decorative art ceramics and porcelain.

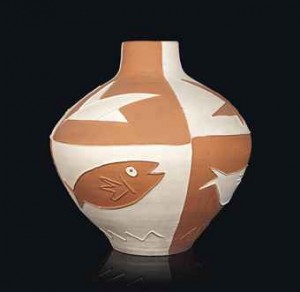

Picasso personally decorated over 4,000 ceramics at the Madoura pottery in the town of Vallauris in the South of France from 1947 to 1972. Most never entered the market. However, editions after 633 of Picasso’s designs were recreated by the artisans at Madoura under the artist’s supervision. These “Edition Picasso” ceramics were at first sold inexpensively to tourists, but such pieces became highly collectible over the years. Edition sizes were anywhere from 25 to 500, bringing the total production to almost 120,000 pieces.

It is thus not uncommon for a personal property appraiser to find Edition Picasso ceramics in an otherwise modest home or estate. Such ceramics, which might have been purchased for less than a hundred dollars in the 1950s or 1960s, can be worth tens of thousands today. Large pieces, which are much rarer than the plates, fish, owls and ashtrays that most tourists brought home, can sell in six figures.

The Jane Kahan Gallery has been dealing in fine art ceramics, especially Edition Picasso pieces, since 1973. We have found that this is not a market that focuses on condition. You do not see Dr. No-type collectors at auctions with black lights and fluoroscopes. Repairs and restorations – as long as they are undetectable to the unaided eye – are rarely discussed in galleries or auction houses, though presumably condition reports would be available if requested. Condition is simply not relevant in the same way it might be with stamps or color field paintings or prints where it is of prime importance. If a piece looks damaged or fiddled with, it’s difficult to sell, either at auction or in galleries. If a ceramic looks perfect, however, then professional buyers (who constitute most of the auction market clientele) treat it as good regardless of what may lurk beneath the surface.

In this litigious society appraisers must therefore be careful with their own opinions, biases and assumptions about condition issues as they relate to fine art ceramics. Regardless of how much an appraiser may believe that condition should affect value, each market has its own realities, which no value formula or guidelines can repeal.

In this litigious society appraisers must therefore be careful with their own opinions, biases and assumptions about condition issues as they relate to fine art ceramics. Regardless of how much an appraiser may believe that condition should affect value, each market has its own realities, which no value formula or guidelines can repeal.

The fact is that perfection was not something that Picasso, nor many other artists, cared about. Picasso cared about the art, he didn’t care about the artifact – a distinction that appraisers reverse to their peril. Picasso never permitted any of his ceramics to be discarded, no matter what their condition issues. There was even a special “mechanic” at Madoura to whom he entrusted the repairs of items that had had firing accidents. We have had at our gallery such a piece, with staples on the back to hold a crack together. This ceramic is pictured in a 1948 magazine with the crack clearly visible. An appraiser inexperienced in the market for fine art ceramics might think this plate is less valuable than a “perfect” piece. Picasso did not think so, nor do many collectors. Nor do we (though we might if it weren’t as attractive and desirable a subject).

In 1951 Chagall created a dinner service as a wedding gift for his daughter. The family used this service at table. Like Picasso’s ceramics, these plates, saucers, cups and platters were soft earthenware. They chipped. A few such pieces entered the marketplace. The chips are as identifiable as fingerprints and make for a compelling provenance. Do they lessen value? We don’t think so. Repairing such damage might even be seen as compromising its integrity.

An appraiser might assume that condition is more important with Edition Picasso ceramics because they were made in quantities, like prints. This is not necessarily the case. However, when an expensive vase falls off the shelf during an earthquake and shatters into pieces, few would argue that there has been a loss. Assessing this loss can present major challenges and traps for appraisers, especially those inexperienced in this sophisticated market.

Consider this parable into which I have incorporated some auction sales and condition issues of a real Edition Picasso ceramic.

Late in 2003, Helene, a fictitious St. Louis appraiser, is called in by a Dr. No (not the same Dr. No who is so scrupulous about condition) to evaluate a large Edition Picasso ceramic vase that accidentally has been broken into pieces. Rather than waiting until the ceramic is repaired and then consulting with experts in this market to determine its post-restoration value, Helene applies percentages suggested in an industry handbook for catastrophic damage to “modern ceramics.” She declares in her loss/damage appraisal that the vase is a total loss, value zero.

The ceramic in question is Oiseaux et poissons, a large and relatively rare vase, number 291 in Alain Ramié’s definitive catalogue raisonne of the Edition Picasso ceramics. A vase from the same edition of 25 had sold at Christie’s London in October of 2002 for $46,590, so Helene puts down this number as the amount of the loss. (The ceramic would probably have been $65,000 or more in a gallery, but Dr. No didn’t have replacement value insurance.)

The ceramic in question is Oiseaux et poissons, a large and relatively rare vase, number 291 in Alain Ramié’s definitive catalogue raisonne of the Edition Picasso ceramics. A vase from the same edition of 25 had sold at Christie’s London in October of 2002 for $46,590, so Helene puts down this number as the amount of the loss. (The ceramic would probably have been $65,000 or more in a gallery, but Dr. No didn’t have replacement value insurance.)

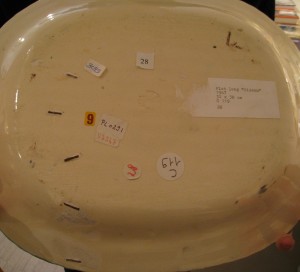

The insurance company takes possession of the shards and has the vase skillfully restored. It then sends it to Sotheby’s in New York, where it goes into a April 2004 sale and sells for $30,000. Already one can see that, by any definition, the “value” of the ceramic is significantly more than zero. In fact Sotheby’s gave it a presale estimate of $40,000 to $60,000, so it is clear that Sotheby’s didn’t seem to care overly that the piece has been repaired (though the words “skillfully restored throughout” are placed into the catalogue entry).

The buyer promptly sends the ceramic to Christie’s London, where it is estimated at ₤20,000 to 30,000 (roughly equivalent to the $40,000 to 60,000 Sotheby’s estimate) and made the cover lot for an October 2004 sale. This time no off-putting mention of restoration is made in the catalogue, but the ceramic does not sell. Note that when Sotheby’s mentioned condition in the catalogue, the piece sold. This time no mention was made, and the piece did not sell.

Condition information is not generally recorded in on-line databases, so potential buyers looking up the auction records for this ceramic wouldn’t have known about the condition of the piece unless they asked for a report from Christies. Few professional buyers of Picasso ceramics are concerned enough to do this, as I have said before. Someone checking the auction databases, however, would have noticed that the last sale of this ceramic was for $30,000, so perhaps the estimate might just have seemed too high for savvy buyers.

In any case Christie’s puts the piece in the April 2005 auction and lowers the estimate to ₤15,000 to 20,000. This seems to do the trick, because the totally restored ceramic sells for ₤31,200 (then $58,646.) to a French dealer, Monsieur Yes (whom I have made up entirely out of whole cloth, as I have the rest of this story, except for the auction

records for this ceramic and its condition issues, which are real). Monsieur Yes has decades of experience with Picasso ceramics. Condition problems are irrelevant to him unless there is a visible problem, which is not the case here (and if there were a visible problem, he would have it repaired). He takes the ceramic back to Paris and subsequently sells it to an American tourist for the equivalent of $125,000 (they get very good retail prices in Paris). He does not disclose that there is restoration because, not having asked for a condition report, he does not know. And even if he did know, in his experience this is not relevant to the value of the ceramic.

The buyer, Mrs. Maybe, proudly ships her prize back home to St. Louis, and early in 2006 she engages Helene the Appraiser to assess the replacement value of her belongings for insurance purposes. Edition Picasso ceramics are numbered, and Helene cannot help but notice that the number of Mrs. Maybe’s Oiseaux et poissons is the same as Dr. No’s. It is the same ceramic.

What dollar value should Helene assign in her appraisal? Two years ago Helene herself had declared this piece worthless. Its fair market auction value of record is $58,646 from the Christie’s sale. Its retail replacement value is the $125,000 for which Mrs. Maybe recently purchased it in Paris – in fact another vase of this type probably could not be found at that point for any price. Similar to Schroedinger’s Cat from quantum physics which found itself in the peculiar position of being both alive and dead at the same time, Mrs. Maybe’s ceramic appears to be simultaneously both worthless and overpriced.

Helene feels ethically bound to disclose the issue of condition of this vase to Mrs. Maybe, but she should think very carefully before she does so. Monsieur Yes does art fairs in New York, Los Angeles and Miami, and he can’t afford to have integrity impugned. He may very well sue if Helene tells Mrs. Maybe that he has sold her a worthless vase for $125,000.

Good luck with your appraisal, Helene.

Copyright @ by Charles Mathes