National Arts Club Lecture: Picasso Ceramics: Fake, Fraud or Genuine?

Join Charles Mathes, AAA for a lecture on Picasso Ceramics. Literally tens of thousands of ceramics were replicated at the Madoura Pottery in the South of France after Picasso’s originals. The secondary market for these Picasso ceramic editions is now larger than ever with internet bidders paying record prices based solely on on-line images. While the vast majority of Picasso ceramics in the international marketplace are genuine, it can be a mistake to assume that everything is what it seems to be. This lecture is not the usual survey of what Picasso ceramics are and how they came to be, but instead what they may not be and what they definitely aren’t.

A reception with refreshments will follow the lecture, which will be held in the historic National Arts Club, a National Landmark building and the former home of Governor Samuel Tilden.

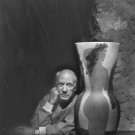

Veteran Appraisers Association Certified member Charles Mathes, AAA, was director of a New York City gallery specializing in Modern Art. Now a consultant and advisor, he has handled and appraised hundreds of Picasso ceramics over the course of his career and has written and spoken frequently on the subject.

Veteran Appraisers Association Certified member Charles Mathes, AAA, was director of a New York City gallery specializing in Modern Art. Now a consultant and advisor, he has handled and appraised hundreds of Picasso ceramics over the course of his career and has written and spoken frequently on the subject.

Event Details

Date:

Monday, May 5, 2025

Time:

6-8 PM ET

Location:

The National Arts Club

The Sculpture Court

15 Gramercy Pk S

New York, NY

Price:

In Person (NYC) $20.00 Members

$25.00 Non-Member

Free CASP Student or Associate Candidate

Register for Event

Picasso Ceramics – Originals, Editions and Variants

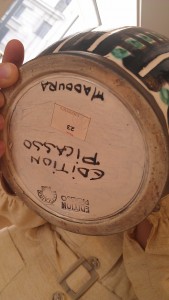

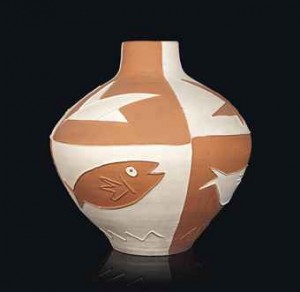

The term “Picasso Ceramics” generally refers to the pitchers, plates, vases and plaques that were recreated by the artisans at the Madoura pottery in the South of France after ceramics personally decorated by Pablo Picasso. These “authentic replicas” and “original prints” were done in editions of from 25 to 500 and were sold inexpensively to tourists until Japanese demand in the 1980s caused a price explosion. For the past thirty years EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS that might originally have been purchased for under a hundred dollars have sold for tens of thousands.

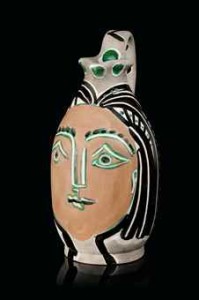

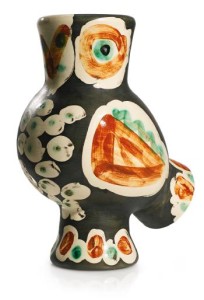

EDITION PICASSO CERAMIC AR 198 – one of 500 copies – sold at Sotheby’s London 4-10-2017 for $13,194

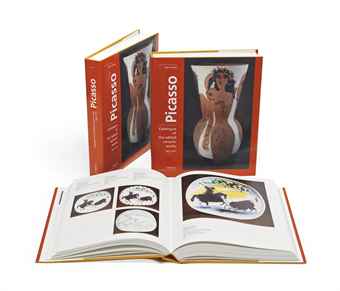

Because this is the age of “art as investment” people talk about the “Picasso ceramic market.” In order really to have a market for something you need a sufficient supply, a minimum trading volume and reliable information. The New York Stock Exchange for instance, requires member companies to fulfill various reporting requirements, have 1.1 million public shares outstanding and a monthly volume of 100,000. If you add up all the EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS (I once did), the total comes to almost 120,000 pieces. There’s a reliable catalogue raisonné and, while public sales of even the larger editions rarely exceed half a dozen per year, there are enough auction records over the past three decades to give the illusion of a market, albeit a thinly traded and highly inefficient one.

PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINAL – personally decorated by Picasso sold at Sotheby’s in May 2017 for $32,500

But what about ceramics that Picasso personally painted? There were over 4,000 of these, including the prototypes after which the EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS were replicated. The vast majority of such PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS were never offered for sale and are now in museums. Though dealers occasionally get hold of one and a few have made their way to auction, there have been years when it would have been difficult to find a ceramic hand-painted by Picasso for sale anywhere in the world. Nor is there anything approaching a definitive reference, though PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS are discussed in a few books including the catalogue for the 1999 exhibition at the Met, “Picasso – Painter and Sculptor in Clay.” Dealers and auction houses like to call such ceramics “Unique,” perhaps not using the word “Original” so as not to draw attention to the fact that the EDITION PICASSO pieces are what some might call reproductions. However, the term “unique” can be misleading, as we shall shortly see.

In June 2015 Picasso’s granddaughter, Marina, put more than two hundred PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS that she had inherited up for auction at Sotheby’s London. Coincidentally there was a sale of EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS the same day across town at Christies, giving a rare opportunity to compare prices of Picasso’s ORIGINALS versus EDITIONS. But adding a couple hundred of Marina’s ORIGINALS to the few already in circulation didn’t suddenly make this a reliable market. This can be seen from the spread between the sale prices and the estimates, which varied by tens of thousands of dollars. In an efficient market (like the NYSE) the difference between the bid and ask can be a penny.

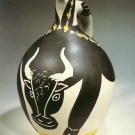

EDITION PICASSO AR 79, one of 300 copies. Between 2014 and 2017 there were more than a dozen sales of this ceramic between about $7,500 and $18,000.

In May 2017 Marina Picasso put more of her inherited pieces up for auction, this time at Sotheby’s in New York. Sotheby’s marketed this batch not as “Picasso ceramics,” but as “Works from the Collection of Marina Picasso.” In fact more than half the sale was comprised of drawings, which also made the three highest prices, but there were also PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS, EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS, as well as another category that most collectors and many dealers are totally unaware of – EDITION PICASSO VARIANTS.

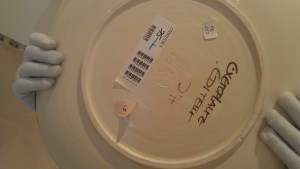

EDITION PICASSO VARIANTS are basically EDITION pieces apart from the official count that were for some reason decorated differently than the ceramics described in Alain Ramié’s definitive “Picasso – Catalogue of the Edited Ceramics.” There is virtually no information available about why such variations were created or how many exist.

PICASSO CERAMIC VARIANT from Marina Picasso Collection brought $30,000 at Sotheby’s NY 18 May 2017

Picasso’s ideas evolved, and he often executed several slightly different versions of a ceramic. Perhaps the VARIANTS were tests, and ultimately a different version was selected for the EDITION PICASSO piece. Another possible explanation is that the artisans at the pottery were just fooling around. Madoura didn’t fire all the pieces of an EDITION at once. A small number were created at a time and another batch was fired only when the existing ones were sold. Maybe there was an extra blank, and someone couldn’t bear to just throw it away. Or maybe Picasso wanted to give a particular ceramic to a friend but the EDITION was closed out, so he just instructed Madoura to make a different, undocumented proof.

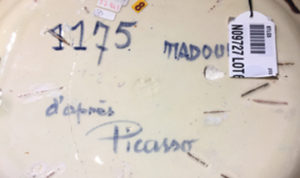

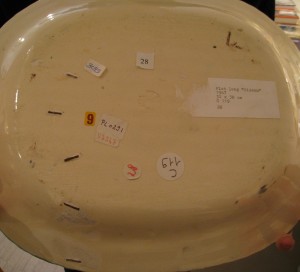

Picasso Dove Variant – reverse.

Whatever the reason for their existence, it’s generally been assumed that EDITION PICASSO VARIANTS were not created by Picasso personally. In the 1950s and 1960s EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS were inexpensive souvenirs; anything that Picasso personally decorated was in a different category entirely and scrupulously documented for the valuable object it was. Thus the VARIANTS that have made their way to auction have been considered mere curiosities and usually sell for prices comparable to the EDITION pieces.

The May 2017 sale of Marina Picasso’s odds and ends, however, has presented a new wrinkle in the status of EDITION PICASSO VARIANTS. The day I went to a viewing only junior people were available at Sotheby’s but I was told that every piece in the sale would come with a certificate from Claude Picasso saying that it was “unique.” Unique in the sense that it was painted personally by Picasso or unique in that it was an undocumented version of the EDITION PICASSO CERAMIC? The junior people weren’t clear, but what’s indisputable is that these ceramics had once belonged to Picasso and were part of the collection that Marina Picasso inherited from her grandfather.

Take a look at the EDITION PICASSO CERAMIC Dove above, AR 79, and the VARIANT from Marina Picasso’s collection. In the auction catalogue Marina Picasso’s Dove is one of the few ceramics in the sale not identified as unique, only as “Painted, glazed and incised ceramic.” It is marked on the reverse “d’apres Picasso” – “d’apres” means “after” in French. The logical conclusion is that it is not from Picasso’s hand; it is simply an EDITION PICASSO VARIANT.

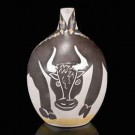

Marina Picasso’s EDITION PICASSO VARIANT Bull’s Profile sold for $62,500

It’s always a good idea to personally inspect an item you wish to buy at auction and to read carefully its catalogue description. Consider Marina Picasso’s Tête de Taureau for example. As with the Dove platter above, the catalogue entry for this Bull’s Profile plaque says nothing about its being unique, just that it’s in reverse in the EDITION piece.

EDITION PICASSO Bull’s Profiles rarely sell for more than $6000.

Yet the ceramic brought $62,500 in the sale, which is curious because there are three different EDITION PICASSO versions of this same Bull’s Profile, adding up to a total of 1000 ceramics, and they generally bring under $6,000 at auction.

Are there other copies of this Bull’s Profile in reverse VARIANT? I have no idea, and as I said before, there is no way to find out. Certainly provenance can add value, but does the fact that Picasso had this VARIANT in his house (over the mantel? in the closet?) make it worth a 1000% premium? If so, why didn’t Marina Picasso’s Dove platter bring ten times the price for that EDITION piece?

Though no claim was made that Picasso personally decorated Marina Picasso’s Dove platter or her Bull’s Profile plaque, the Sotheby’s auction catalogue does give us some new information about VARIANTS, unequivocally stating: “Sometimes the decoration [of empreintes] would be replicated for the editions, but all the examples in the Marina Picasso collection were painted or otherwise decorated by the artist himself.”

Marina Picasso’s Unique Version of an Empreinte Picasso brought $137,000.

“Empreinte originale” – also called “Original Print (or O.P.)”- was a technique whereby a mold reproduced Picasso’s raised structures in the wet clay. The catalogue description of each of such VARIANTS in the Marina Picasso collection calls it “a unique version of the empreinte.” So now we know that Picasso did personally create some VARIANTS, including a “unique version of the empreinte” Tête de Chevre (Goat’s Head), which sold for $137,000. (There are five different EDITION PICASSO versions of similar Goat’s Head empreintes in the catalogue raisonne (Ramié 151 – 155). Marina Picasso’s piece is a VARIANT of AR 154, the only EDITION Goat’s Head that has four Xs.)

EDITION PICASSO CERAMIC AR 154. Goats Heads of the five different types generally bring between about $10,000 and $30,000 at auction

So are there any other “unique” copies of this same Goat’s Head VARIANT? The answer is yes – sort of. Another ceramic much like the one illustrated above came to auction on April 25, 2012, at Phillips de Pury & Co. in New York, where it was even described in the auction catalogue as “a unique variant” and sold for $21,250. The Phillips catalogue reported “There is an extremely similar image of a unique piece in the Marina Picasso Collection (Picasso Keramiek 1985 Museum Het Hruithuis).” Why was the Phillips “unique variant” created? Who decorated it and had the audacity to include nine yellow balls instead of the ten Picasso used in Marina’s ceramic?

EDITION PICASSO VARIANT Goat’s Head brought just $21,250 in a 2012 auction at Phillips

Because different artisans replicated the EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS by hand after Picasso’s ORIGINALS, every EDITION piece is “unique” in that sense. Of necessity all VARIANTS were individually painted, too, and subtle differences in shapes and lines can always be found between two hand-painted recreations. You can see these for yourself if you examine this third VARIANT Goat’s Head that I found advertised on a dealer’s website as a “unique color variant.”

Another Picasso Goat’s Head “unique” variant

If “unique” VARIANTS aren’t enough to drive you crazy, there was actually a fourth category of Picasso Ceramics that were included in the Marina Picasso Sotheby’s May 2017 sale: damaged pieces. Remember that “d’apres Picasso” Dove platter EDITION PICASSO VARIANT? It had a great big crack right down the middle. Was this reason why it didn’t fetch more than about twice the price of the EDITION piece?

Picasso didn’t consider any ceramic a mistake that should be discarded; he believed something could be always be learned and even designated one of the Madoura artisans as his “mechanic” who would repair pieces that had been damaged in the firing. Several PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS in this sale in fact had staples visible on the back to hold cracked pieces together.

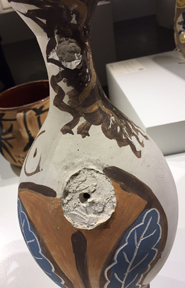

A cracked Picasso ceramic showing staples holding it together

Perhaps the VARIANT Dove became part of the Marina Picasso Collection because, no matter who had painted it, Picasso liked it despite the damage and took it home. After all, Picasso was the man who took a little owl with an injured claw home to live with him and Francois Gilot when he first came to Antibes in 1946. It was this owl that in fact inspired a number of his ceramics.

Marina Picasso’s unique Goat’s Head empreinte (it might be clearer to call it a PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINAL – EDITION VARIANT) also had damage clearly visible on the reverse.

Marina Picasso Goat Head damage

So if Picasso didn’t care about damage, should potential buyers? Apparently the buyer of Ms. Picasso’s Goat’s Head VARIANT didn’t, if he or she was even aware that the plate had a crack. These days a lot of auction buyers don’t attend previews or even ask for condition reports, they just look at on-line pictures which rarely focus on a lot’s flaws. Certainly if there are three hundred copies of an EDITION PICASSO CERAMIC and one comes up for sale with a big chunk missing from the rim, people will likely want to wait for a better copy to their collection. However, earthenware ceramics can restored so expertly that even experienced dealers can’t detect any trace of damage by eye, and how many people really demand condition reports on pieces that look perfect? (For a discussion of how restoration can affect value of EDITION pieces, click here.)

With Picasso ORIGINALS, damage may not affect value at all. When casino magnate Steve Wynn put his elbow through Picasso’s painting La Rêve, which hedge fund honcho Steve Cohen had agreed to purchase for $139 million, Wynn sued his insurance company for $54 million in lost value. The suit was settled for an undisclosed amount, but a few years later Cohen turned around and bought the restored La Rêve anyway for $155 million, $16 million more than he was going to pay originally. After all, La Rêve was still a great Picasso, and it wasn’t like Cohen could go out an buy an undamaged version.

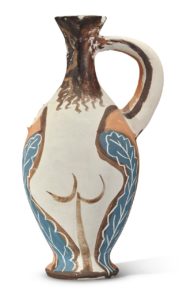

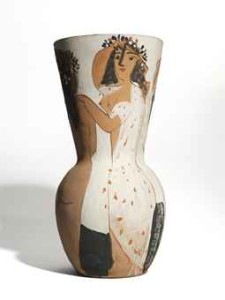

Because of paucity of supply and lack of information, the market for PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS is so thin as to be practically non-existent. Consequently damage to such items may in fact present unique opportunities. Consider the top ceramic lot in Sotheby’s May 2017 sale of works from the Collection of Marina Picasso, Vase-femme Avec Bras-Anse, (Woman Vase with Arm Handle)” which brought $250,000.

The catalogue visual of PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINAL, Vase-femme avec un bras-anse

The vase’s rear end

Picasso’s son, Claude, in an essay in “Picasso, Painter and Sculptor in Clay” described how much of a challenge it was for his father to decorate a three dimensional object and how Picasso utilized the forms themselves in creative and whimsical ways – painting the picture of a vase on a vase, turning a handle into a flower, etc. Vase-femme Avec Bras-Anse is a perfect demonstration of how Picasso didn’t merely accept the limitations of shapes but used them to create something even better. However, many potential bidders may have seen only damage if they attended the preview. In the sale room it was evident that the “Arm Handle” had been restored and there had originally been another matching arm on the other side that was now missing entirely!

Picasso Original Repaired Arm

Picasso Original Missing Arm

Despite the damage the ceramic still soared above its $40,000 – $60,000 estimate. I think whoever snapped up this piece still got a tremendous bargain, even if he or she were one of those on-line buyers who had looked only at the pretty pictures in the auction catalogue and fainted when they opened the box. After all, $250,000 is a small price to pay for what is arguably a great PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINAL. I mean we’re talking about just 1/1000th (all right, 0.00161290322%) of the $155,000,000 that Steve Cohen wound up paying for La Rêve! Who do you think got the better deal?

I think it’s extremely likely that the next time Vase-femme Avec Bras-Anse surfaces it will have both arms intact and no evidence that either of them had ever been anything other than perfect. Even if the new owner is a dealer who wants to make a big profit on the piece there would be no reason to conceal that it had been skillfully restored – a potential buyer will be hard-pressed to find a similar ceramic at any price.

Unique Picasso Ceramics vs. Madoura Editions

The market for Edition Picasso ceramics is hot. The auction prices of some pieces have soared 500% and more from one year (or one sale) to the next.

I’ve discussed the reasons for this explosion of interest before (the Runaway Bull, the Runaway Bull Returns, the High-Flying Owl), reminding people that the Edition Picasso Ceramics were not personally painted by Picasso. Though Picasso decorated over 4,000 ceramics, the Edition Picasso is comprised of some 600 “authentic replicas” recreated after Picasso’s unique prototypes by the artisans at the Madoura pottery in the South of France.

This Edition Picasso “Tête de chèvre de profil” AR 148 sold at Sotheby’s Paris on May 21, 2015, for $19,468.

When people hear about this distinction their initial reaction is often that they don’t want to buy “reproductions,” only originals. Unfortunately original Picasso paintings can cost as much as $179,365,000 at auction. A desirable Edition Picasso ceramic can sell for 1/10,000th of that (the Goat plate illustrated above brought only 1/9,213th of the record painting price, but you get the idea). No wonder these multiples quickly became collectable after their introduction in 1948 when they were sold as inexpensive souvenirs to vacationing tourists. That’s right, Edition Picasso ceramics purchased for fifty dollars in the 1950s are today worth tens of thousands.

So you would figure that the ceramics that Picasso personally decorated would be a lot more valuable than the ones that were replicated, right? Well, yes and no. Yes, they’re worth more. But no, they’re not worth 10,000 times more, or even 1000 times more. Or even 100 times more. Or, often, even 10 times more. And some of them have recently sold for less than Edition pieces.

One reason for this anomaly is the very rarity of Picasso’s “original” ceramics, most which were never commercially available. People equate rarity with value, but prices are determined in the marketplace. Picasso kept the vast majority of the unique pieces for himself and most ended up in museums or with members of the artist’s family. Consequently, the kind of competition that makes prices rise never developed for originals – they rarely came up for sale. However as early as the 1970s the approximately 120,000 ceramics in the Edition Picasso began appearing at auction. If a collector wanted an Edition Picasso ceramic there was a huge selection immediately available, but if he wanted a ceramic that Picasso himself had painted he might wait years before one appeared. The very term “Picasso ceramic” came to mean one of the multiples replicated by the artisans at Madoura.

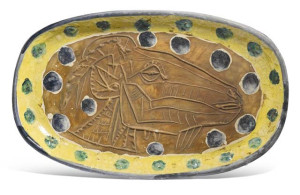

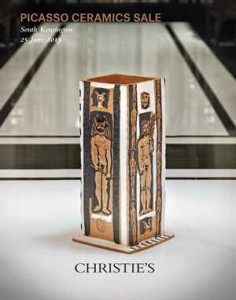

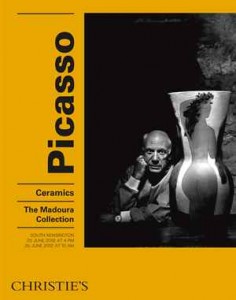

It’s therefore doubly difficult to compare values for unique Picassos and Edition Picasso pieces, since not only do auction results swing wildly from place to place and year to year, there just isn’t much comparable sales data. Because of a rare coincidence, however, we now have a unique opportunity to make such price comparisons. In London on June 25, 2015, Sotheby’s sold a collection owned by Marina Picasso of over 100 ceramics personally painted by her grandfather (Marina is the daughter of Picasso’s son Paulo and his first wife, Olga Khokhlova). On the same day in another part of town there was a dedicated sale of Edition Picasso ceramics – at Christie’s South Kensington, the venue that has accounted for many of the recent record-breaking sale prices.

While comparing apples and oranges is still easier than comparing most of the ceramics in these two sales, some pieces are directly equatable. For instance, take a look at these two pieces:

The one on the left is from the Edition Picasso, Picador et taureau, AR 194, from the edition of 200 (the “AR” number is from Alain Ramié’s definitive catalogue raisonné). The one on the right was entitled Tauromachie in Marina Picasso’s collection, a unique ceramic hand-painted by Picasso — almost certainly the prototype for the Edition piece.

The AR 194 Edition Picasso Picador et taureau plate brought the equivalent of about $10,780 at Christie’s South Kensington. At the Sotheby’s sale across town the comparable unique piece sold for the equivalent of $68,800. Granted that neither one of these ceramics is a great work of art. In fact if you had been at Madoura in 1953 the Edition piece was probably one of the Picasso tsotchkes priced at five or ten bucks. But if you use these two ceramics as a guide, a Picasso “original” is worth 6.38 times more than the Edition Picasso piece.

However, another pair of ceramics tell a different story:

In the Christie’s sale, the AR 296 Edition Picasso ceramic, pictured on the left, sold for $27,440 (I’m using the auction houses’ conversions to translate all of these prices from pounds to dollars). The one of the right, one of Marina Picasso’s unique pieces, sold for $94,354 at Sotheby’s. The market — as well as your eyeballs — might suggest that these ceramics are “better” than the Picador plates. However, using these vases as a guide, a Picasso “original” is worth only 3.43 times more than the copy. Why does a “better” original bring a smaller multiple?

In the Christie’s sale, the AR 296 Edition Picasso ceramic, pictured on the left, sold for $27,440 (I’m using the auction houses’ conversions to translate all of these prices from pounds to dollars). The one of the right, one of Marina Picasso’s unique pieces, sold for $94,354 at Sotheby’s. The market — as well as your eyeballs — might suggest that these ceramics are “better” than the Picador plates. However, using these vases as a guide, a Picasso “original” is worth only 3.43 times more than the copy. Why does a “better” original bring a smaller multiple?

The most expensive piece in Sotheby’s sale of Marina Picasso’s ceramics, by far, was described as a vase but seems more of a sculpture than the usual shapes and plates in the Edition Picasso. It sold for $762,698 and is pictured at the top of this page. No Edition Picasso ceramic is even remotely comparable to this piece. The top lot in the Christie’s sale was Femme du Barbu (the Bearded Man’s Wife), AR 193, which sold for $163,856. Using these two ceramics as a guide you might conclude that the best Picasso original is worth 4.65 times more than the best Edition Picasso multiple.

Of course it is worth noting that Femme du Barbu is hardly among the “best” Edition Picasso ceramics. For starters it’s an edition of 500, the largest edition size made. I’ve found 16 other sales of this ceramic since 2013 with an average sale price of about $30,000 (until the Madoura sale in 2012 they brought much less). Femme du Barbu was estimated in the Christie’s catalogue for about $19,000 – $28,000. In short, it’s a fairly large, very common ceramic, and it’s whimsical and fun. But you can say the same about many, many other pieces.

So in the interest of fairness let’s look at what actually is considered to be the “best” Edition Picasso ceramic because of its scale, rarity, beauty and renown: the Grand Vase, AR 116. This ceramic is over ten inches larger than Femme du Barbu, it’s from an edition of just 25 (the smallest produced), it is pictured on the cover of the Alain Ramié’s catalogue raisonné and in a famous photograph of Picasso by Henri Cartier-Bresson. One of these pieces made the auction record for an Edition Picasso ceramic: $1,144,268 at the much hyped “Madoura” sale in 2012. Another brought $1,080,221 in 2014. Thus using the Grand Vase as a guide, the best “original” Picasso ceramic in Marina Picasso’s collection was worth less than the best Edition Picasso piece!

Prototype for Picasso “Grand Vase” AR 116 which brought a record $1.5 million. One of the 25 Madoura Edition Picasso copies brought $1.14 million.

If you want to get picky, at $762,698 Marina Picasso’s unique vase pictured above isn’t the “best” unique Picasso ceramic ever to sell at auction, at least in terms of price. Ironically that honor belongs to Picasso’s prototype for the same Grand Vase that set the record for most expensive Edition Picasso ceramic. This prototype sold in 2013 at Christie’s in London for $1,534,557. In other words, the original sold for only 1.5 times more than the copy.

Clearly something is screwy here. Either Edition Picasso ceramics are overpriced, unique Picasso ceramics are underpriced, or a combination of both. To say nothing of the possibility that the entire art market may presently be in the same kind of mania that precedes stock market crashes (and the fact that it’s silly to try to draw conclusions from individual sales in thinly traded, inefficient markets).

Regardless of whether an entire market is elevated or depressed, however, certain ratios should be constant unless there is a fundamental paradigm shift as there was in the 1970s and 1980s due to the influx of Japanese buyers. In Western culture, oil painting is the most important fine art; ceramics are less important. In Asia it’s just the opposite. When the Japanese entered the market, they were willing to pay vastly higher prices for ceramics than anyone ever had before. When they stopped buying at the beginning of the 1990s, prices crashed.

Unique Picasso Goat plate from Marina Picasso’s collection sold at Sotheby’s in June 2015 for $176,914

Let’s return for a moment to that $179 million record-price Picasso painting, and the fact that you can get a fine Edition Picasso ceramic for about 1/10,000th of that. The Tête de chèvre (AR 148) platter from the edition of 100 pictured at the top of this page is an example of such a bargain at a sale price of $19,468. If you believe in numerology (and the metric system) you’ll be interested to learn that Picasso’s probable prototype for Tête de chèvre sold for $176,914 in the Marina Picasso sale at Sotheby’s, about ten times more than its Edition Picasso equivalent but close to 1/1,000th of the record-price Picasso painting.

So, how much more should unique Picasso ceramics be worth than comparable Edition Picasso pieces? If the answer is 1000 times, then the Grand Vase prototype should have brought at least a BILLION dollars — 1,000 times the $1+ million that the two Edition Picasso Grand Vases have recently sold for. If the answer is 100 times, then the best originals should be somewhere between $50 and $100 million — 100 times the $500,000+ prices that many other Edition Picasso Grand Vases have brought at auction. If it’s a mere 10 times, as the the two  Goat plates would seem to suggest, then best original Picasso ceramics should sell in the $10,000,000 range. If the other examples compared above are better guides, then the best unique pieces should be $6,380,000 or $3,430,000, 0r $4,650,000 — in all cases significantly more than they have actually been selling for. To my mind the buyer of the beautiful Picasso at the top of the page got a steal.

Goat plates would seem to suggest, then best original Picasso ceramics should sell in the $10,000,000 range. If the other examples compared above are better guides, then the best unique pieces should be $6,380,000 or $3,430,000, 0r $4,650,000 — in all cases significantly more than they have actually been selling for. To my mind the buyer of the beautiful Picasso at the top of the page got a steal.

Clearly Christie’s believed that the “best” Edition Picasso ceramic in their sale of June 25, 2015, was Personnages et Têtes AR 242. At 22 inches tall, not only was it the largest piece in the sale, it was one of only 25, the smallest edition size produced at Madoura. It was pictured on the cover of the catalogue and brought the second highest price in the sale (after the outlier Femme du Barbu ), selling for $145,040 — over twice its low estimate ($62 ,000 – $92,000). Yet more than half of the unique Picasso ceramics from Marina Picasso’s collection at Sotheby’s sold for less than the cost of this Edition Picasso multiple. Granted that the originals were smaller in size and arguably less interesting than Personnages et Têtes, but they were actually from the artist’s hand, not “authentic replicas.”

Which would you rather own?

Value Mysteries: Picasso Ceramic Owls

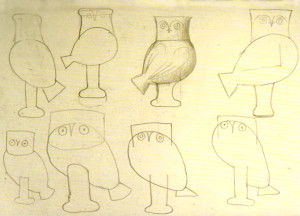

In 1946 Picasso was staying near Antibes in the South of France and decorating the walls of what would become the Musée Picasso. A small owl with an injured claw that had been found in a corner ended up living with him and his lover, Francois Gilot. According to Gilot in her book “Life With Picasso” the owl was an ill-tempered creature who smelled awful and ate only mice. The owl would snort at Picasso and bite his fingers; Picasso would reply with a string of obscenities just to show the bird who was the most ill-tempered. Clearly bad manners were the way to Picasso’s heart for not only did he do a number of paintings, drawings and prints of owls, he created numerous ceramics.

While it is true that Picasso didn’t create most of the ceramic shapes that he decorated at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris (though he did manipulate many of the forms — bent them to his will, if you will), it was not until after the artist’s death did sketches come to light that proved Picasso had in fact executed designs for ceramics around the time the little owl was regurgitating hairballs around the house.

While it is true that Picasso didn’t create most of the ceramic shapes that he decorated at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris (though he did manipulate many of the forms — bent them to his will, if you will), it was not until after the artist’s death did sketches come to light that proved Picasso had in fact executed designs for ceramics around the time the little owl was regurgitating hairballs around the house.

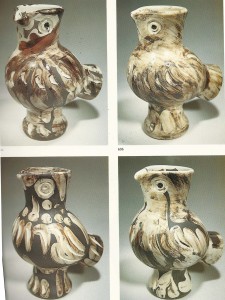

Take a look at five ceramics below that were created at Madoura in 1951. One of them was painted personally by Picasso. The others were painted by the artisans at the pottery after Picasso’s original, what are called “authentic replicas” in the Ramié catalogue raisonne and what are commonly known as Edition Picasso Ceramics. Can you tell which is the one painted by the artist?

This isn’t the value mystery by the way, although Picasso’s unique prototypes usually command prices at least ten times higher than the editions. We’ll get to the value mystery shortly. First, however, it will be useful to understand how relatively common this owl shape was in the entire set of 633 Picasso ceramics that were made into editions.

This isn’t the value mystery by the way, although Picasso’s unique prototypes usually command prices at least ten times higher than the editions. We’ll get to the value mystery shortly. First, however, it will be useful to understand how relatively common this owl shape was in the entire set of 633 Picasso ceramics that were made into editions.

Of the edition owls above one was of 500 (Picasso ceramics were made in editions of between 25 and 500), so it is not particular rare. The other three were from editions of 300, so already in 1951 there were 1400 owls of this shape flying out of Madoura. You might think that there were really 1401 counting the one that is Picasso’s unique piece, but you would be wrong. In addition to the unique piece (the fourth in the lineup above) which was not made into an edition, there were prototypes for the four other owls that were replicated plus, undoubtedly, other paintings by the artist of this shape. The essence of Picasso’s genius was his being able to tap into a virtually inexhaustible creativity. Once the artisans at the Madoura pottery had created Picasso’s owl shape in ceramic they would have given him some fired pieces which he would have begun decorating. It was not unusual for Picasso to paint a dozen ceramics in a day or more. Altogether he painted over 4000 pieces at Madoura, only 633 of which were made into editions.

There were other owl shapes decorated by Picasso but this, his own, clearly remained one of Picasso’s favorites. A new edition of 300 differently painted owls of this same shape were produced in 1952. In 1958 another edition was created, this one of 200 pieces (the smallest edition of this particular form), not with a white glaze but just the terracotta clay as the mat finish. Ten years later, in 1968, Picasso decorated two more owls in his most complex and colorful design, each editions of 500. A year later, in 1969 just a few years before his death Picasso returned to the shape again with six new pieces — some of his last ceramics, also in large editions. If you add up all the edition owls of this particular shape the total comes to 5,250. Since some shapes were painted just once by Picasso in editions as small as 25, it is safe to say that these owls not only are not rare, they are actually among the most common of the three-dimensional Edition Picasso ceramics.

Now consider these four different versions of the form — all from 1969 — and therein lies the mystery:

These owls are regularly estimated at about $6000 – 8000 at auction. However, one of them — or I should say a piece from one of these editions — sold at Sotheby’s London on March 19, 2013, for the equivalent of $75,590.

These owls are regularly estimated at about $6000 – 8000 at auction. However, one of them — or I should say a piece from one of these editions — sold at Sotheby’s London on March 19, 2013, for the equivalent of $75,590.

Was that particular version some kind of weird rarity? No, it was simply one of the 500 copies in the edition, which are all supposed to be virtually identical replicas of Picasso’s prototype. Is one of these versions somehow “better” than the others from 1969 (or all the other 5,249 Edition Picasso owls of this shape)? No. In fact these four ceramics are often miscatalogued because they resemble one another so closely and because of their muddy palette they have historically sold for less than some of the more colorful pieces of the same form.

So what gives?

I have spoken about the wild price fluxuations in Picasso Ceramics before, which started with the “Madoura” sale at Christie’s London in June 2012. A lot of it boils down to a thinly traded market, lack of information and clever people trying to exploit one another. The $75,590 owl was Ramié 605, the first owl in the second row, but the huge price wasn’t made at the 2012 Madoura sale. While a copy of Ramié 605 did soar in that sale above its 3000 – 5000 British Pound estimate to achieve 10,625 pounds ($16,554), which was in fact a record high for the ceramic, that price was bested at the Sotheby’s London 2013 sale by almost 400%.

At Sotheby’s 2013 sale several other Picasso ceramics achieved prices higher than pieces from the same editions had at Christie’s historic Madoura sale the previous year. Perhaps the reason was that Sotheby’s, taking a cue from its competitor, had started to specifically target Chinese and Russian buyers. These collectors were already spending big money at the evening sales of Picasso paintings and drawings, the estimates of most of which started at over a million bucks. It was — for them — a new notion that they could pick up Picassos for less than $100,000. So you paid two or three times the estimates – the auction houses often kept estimates low just to get the action going. What bargains!

Of course when you are dealing with a lot of clever people all of whom are trying to outsmart one another reversals aren’t uncommon. There’s probably even Chinese and Russian words equivalent to the one we use in English when there’s a second reversal after the first: the double cross. Lately it’s come to light that some Chinese buyers haven’t paid for items they’ve won at auction. So perhaps once the buyer had a chance to consider things, the record price was something that existed only on paper (and in auction records), not in fact. And maybe underbidders researched the market a bit more thoroughly after the $75,590 record. Six copies of Ramié 605 have traded at auction since 2013 at prices ranging from $15,000 – 20,000 (Ramié 604, 606 and 607 have performed similarly).

Every sale is different, and when you are dealing with thinly traded items anything is possible. You only need two bidders to make an auction. If they both have a lot of money and perhaps not enough information then the sky’s the limit. The owl below, one from an edition of 300, just sold (18 March 2015) at Sotheby’s in London for 37,500 pounds ($55,343) against an estimate of about $4,400 – 7,300. At the same sale four other versions of owls of this shape sold for between $13,000 and $24,000.

There’s one more wrinkle to this story. After the $75,590 record, knowledgeable collectors who had copies of Ramié 605 (or Ramié 604, 606 and 607) decided that their ceramics, too, were suddenly worth $75,000. Not surprisingly they haven’t been overanxious to consign the pieces to auction where they are still estimated $6,000 – $8,000, and it’s hard to find a dealer with one of these pieces whose asking price starts at lower than $75,000. Thus while demand remains strong the supply actually available for sale is far less than the real supply. Just a few birds fly out periodically, which may be why they still bring Madoura Sale prices.

There’s one more wrinkle to this story. After the $75,590 record, knowledgeable collectors who had copies of Ramié 605 (or Ramié 604, 606 and 607) decided that their ceramics, too, were suddenly worth $75,000. Not surprisingly they haven’t been overanxious to consign the pieces to auction where they are still estimated $6,000 – $8,000, and it’s hard to find a dealer with one of these pieces whose asking price starts at lower than $75,000. Thus while demand remains strong the supply actually available for sale is far less than the real supply. Just a few birds fly out periodically, which may be why they still bring Madoura Sale prices.

But if everyone gets nervous that the market won’t sustain these prices and a few dozen or hundred (or thousand) owls were to fly out at the same time, look out below.

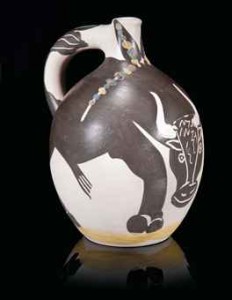

Value Mysteries: Picasso’s Runaway Bull Returns

In my previous post I discussed the Case of the Picasso Ceramic Bull, “Taureau” as he is called in Alain Ramié’s definitive ““Picasso – Catalogue of the Edited Ceramic Works, 1947 – 1971.” Alain Ramié is the son of the Georges and Suzanne Ramié who created Picasso’s edition ceramics at the Madoura pottery.

The first of these Taureaus (AR 255 as it is identified in the catalogue raisonne) to sell at auction brought $87,000 in 1990. For the next two decades, however, at least eighteen other bulls from the edition of 100 sold (or were passed) at auction for prices averaging in the $20,000s. As late as April 2010 one sold at Christie’s in New York for $27,500. In October that same year another brought $25,000 at Sotheby’s New York. But something very strange happened at the next sale of AR 255, which took place at Christie’s South Kensington on June 25, 2012. The price was 97,250 British pounds — $151,263!

The first of these Taureaus (AR 255 as it is identified in the catalogue raisonne) to sell at auction brought $87,000 in 1990. For the next two decades, however, at least eighteen other bulls from the edition of 100 sold (or were passed) at auction for prices averaging in the $20,000s. As late as April 2010 one sold at Christie’s in New York for $27,500. In October that same year another brought $25,000 at Sotheby’s New York. But something very strange happened at the next sale of AR 255, which took place at Christie’s South Kensington on June 25, 2012. The price was 97,250 British pounds — $151,263!

What the hell happened in the intervening year and half that drove the price of Picasso’s ceramic Taureau up 500%?

To answer that question it is helpful to go back to last post where I discussed the factors that drove the price of the first Bull into record territory:

“Market inefficiency drives price volatility and, as with many markets, there are three factors that create inefficiency for Picasso ceramics: lack of knowledge, thin trading and what some people might call manipulation but which in reality is simply the interaction of small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.”

Did any of these three factors exist after twenty years of stable prices for this ceramic? You’d think all the angles had been covered by now, and everybody knew all there was to be known, wouldn’t you?

Did any of these three factors exist after twenty years of stable prices for this ceramic? You’d think all the angles had been covered by now, and everybody knew all there was to be known, wouldn’t you?

But in fact all of these conditions still existed on June 25, 2012 when “The Madoura Collection” went up for sale in South Kensington. Parsing the facts, however, is difficult because in the art market — as in quantum physics — the facts change depending on how they are observed and by whom.

Let’s not call it manipulation because Christie’s in fact was smarter than everyone else when they packaged hundreds of ceramics that had been consigned by Alain Ramié into a hugely publicized, once-in-a-lifetime, sale-of-the-century type affair on June 25, 2012.

Looking like it had been made yesterday, this Grand Vase was the Madoura Sale’s top lot, selling for the equivalent of $1,146,143

Christie’s sale rooms in South Kensington were a perfect venue — one of the priciest neighborhoods in the world and the kind of place where the street traffic is comprised of billionaires. Right there in the window were scads of these charming, wacky Picasso pots and plates, which probably a lot of billionaires and their sisters and their cousins and their aunts had never seen before. These are the sort of folks who usually only bother with the big evening sales where even “restaurant Picassos” start at a couple million bucks. (“You know, Restaurant Picassos,” as Steve Wynn once educated me. “They’re not good enough for my museum so I put them in the restaurant.”) Here was an opportunity to pick up a genuine Picasso with the best provenance imaginable in such pristine condition that it looked like it had been made yesterday for estimates that began at a mere 1,000 pounds or even less. Stocking stuffers!

People who attended the previews reported that these were the archive copies of the Madoura pottery, the “bon à tirer” pieces, the very prototypes approved by Picasso so that editions could be recreated and sold inexpensively (originally) to the tourists. Strangely the Christie’s catalogue itself did not mention any of this, other than to identify the sale as “the Madoura Collection” and specify the edition size. In other words you might have bought the story but as in any auction you weren’t buying actual documentation beyond what was printed in the lot description.  Many of the ceramics were marked “Exemplaire Editeur,” which led to a lot of grumbling among cynics and old-time dealers who had been buying ceramics directly from Madoura — in some cases since the 1960s — and had never heard of anything marked “Exemplaire Editeur.” Nothing about Exemplaire Editeurs had been mentioned in the catalogue raisonne. How many of these things were there and when were they really made?

Many of the ceramics were marked “Exemplaire Editeur,” which led to a lot of grumbling among cynics and old-time dealers who had been buying ceramics directly from Madoura — in some cases since the 1960s — and had never heard of anything marked “Exemplaire Editeur.” Nothing about Exemplaire Editeurs had been mentioned in the catalogue raisonne. How many of these things were there and when were they really made?

The same people also complained that the person who Christie’s (and Sotheby’s) trusted to judge the authenticity of Picasso ceramics was the same person who consigned the pieces, a rather serious conflict of interest! No matter. It wasn’t the cynics who were going to buy at the Madoura sale, any more than they would have shelled out a thousand dollars for a $50 cookie jar at the Andy Warhol Estate sale or God only knows how much for Jackie Kennedy’s dental floss. The once-in-a-lifetime Madoura sale was geared toward once-in-a-lifetime buyers — this was their last chance to buy directly from the source. And buy they did. The two-day Madoura Collection sale was a huge success, taking in over £8,000,000 ($12,500,000), four times its total presale estimate, and was 100 percent sold by lot and by value.

It is interesting to note that not all of the ceramics in the Madoura sale were Exemplaires Editeur. Some were ordinary numbered and unnumbered production pieces. Others bore strange numbering like 113/157/200. A “Grand Vase” that sold for £265,250 was marked H.C 1/3. H.C. is an abbreviation for Hors Commerce, which basically meant not for sale. There is no mention of H.C. Picasso ceramics in the catalogue raisonne. These ceramics skyrocketed past their estimates like everything else.

When the purchasers go to sell their copies, will the market reward them for coming from the historic Madoura Sale (presuming the buyers have kept their receipts)? Or will they find their ceramics valued just like all the hundreds of identical others in the editions?

When the purchasers go to sell their copies, will the market reward them for coming from the historic Madoura Sale (presuming the buyers have kept their receipts)? Or will they find their ceramics valued just like all the hundreds of identical others in the editions?

And what about Taureau, AR 255, Picasso’s Bull that ran away in value? Will it continue to bring a huge premium over its bovine brethren?

In fact a year later the price of Taureau was down by more than half, an example from the edition selling at Christie’s New York for $68,750. A few months later Christie’s South Kensington did better, getting the equivalent of over $91,000 for one (rumor has it that they specifically targeted Chinese internet buyers who had no idea that genuine Picassos could be had so cheap). Not bad, but of course not in the same league as that Exemplaire Editeur Taureau that garnered $151,263 at the Madoura sale. How much, I wonder, is that once-in-a-lifetime ceramic worth today?

In fact, buried at the bottom of the definitions and abbreviations page of Alain Ramié’s catalogue raisonne is the note that there are three “publisher’s copies” for each piece. So perhaps there will be two more “once-in-a-lifetime” Madoura sales in the future. But an Exemplaire Editeur Taureau may not be in both: I appraised one purchased directly from Madoura in 2005.

Value Mysteries: The Case of the Runaway Picasso Bull

Working at the Madoura Pottery in the village of Vallauris in the South of France Pablo Picasso hand-decorated over four thousand ceramics between 1947 and his death in 1973. Over 600 of these were selected to be replicated in editions of 25 to 500 by the artisans at the Pottery and sold inexpensively to the tourists. For the last thirty some years they have been bought and sold at auctions and in galleries around the world. Studying these sales can bring fascinating insights into markets in general and the art world in particular.

Market inefficiency drives price volatility and, as with many markets, there are three factors that create inefficiency for Picasso ceramics: lack of knowledge, thin trading and what some people might call manipulation but which in reality is simply the interaction of small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.

Ironically, until recently the highest prices for Edition Picasso ceramics were achieved in the 1980s when the Japanese appeared to be on the verge of taking over the world. At the beginning of the decade it was the Japanese who knew something that everyone else didn’t: that ceramics had always been the true fine art in Japan, a culture where oil painting had not traditionally existed. Tremendous wealth was flowing toward Japan and the Japanese wanted to experience the best that the Old World had to offer in luxury products, fashion, food, entertainment and of course art. Well-heeled Japanese who weren’t rich enough to buy important European paintings could pay twice the asking price for a Picasso plate and feel they had gotten a tremendous bargain. Prices soared. By mid-decade Sotheby’s and Christie’s, which for years had turned up their noses at Picasso ceramics as mere tourist curiosities, began to include them in sales. Prices went even higher. Yet few people understood what these items were, where they were made, who made them and how many were created.

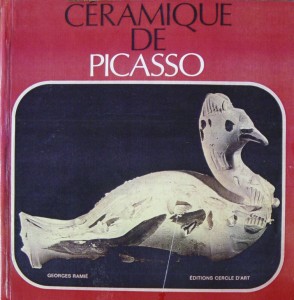

Because Picasso ceramics were low-priced vacation “souvenirs,” there was little published information available. Not even the book written by the owner of the Madoura Pottery, Georges Ramié (which was only available in French for several years), offered much hard data. Georges Ramié’s “Ceramiques de Picasso” pictured various of Picasso’s unique prototypes without explaining that there were perhaps hundreds of “authentic replicas” of the pictured pieces. This inevitably led to confusion among buyers and sellers alike as to whether ceramics were originals or edition pieces (in fact the vast majority of ceramics decorated personally by Picasso were never for sale and are still owned by members of the Picasso family and museums).

When this Bull appeared at auction it was probably the first time that anyone in the prestigious sale rooms had ever seen anything like it. But novelty wasn’t the only reason that this Bull sold at Sotheby’s London on October 18, 1990 for 44,000 British Pounds, then the equivalent of $87, 824. Knowing that the Japanese were voraciously pursuing Picassos a dealer may have made the top bid for this ceramic, figuring he could sell it to some rich fool in Tokyo. It only takes two bidders to achieve a record auction price and unknowingly the buyer might have been bidding against the one Japanese collector who would have paid a top retail price for this ceramic. Or perhaps there was a second dealer who thought he too was smarter than everyone else, was willing to take risks and believed there was no limit to the Japanese mania for Picasso ceramics. We’ll never know. What we do know is  that one month later, on November 19, 1990 another Picasso ceramic Bull just like the first sold for $39,600 at Christie’s in New York City.

that one month later, on November 19, 1990 another Picasso ceramic Bull just like the first sold for $39,600 at Christie’s in New York City.

A 55% decline in one month would be considered a crash in any market (the great Stock Market Crash in 1929 was a mere 12.82%). Certainly one factor in the price decline was lack of information, but that was about to change — sort of. In 1989 Alain Ramié, the son of Georges, published “Picasso – Catalogue of the Edited Ceramic Works.” I say “sort” of because both Georges and Alain Ramié’s books were popularly referred to as the Ramié Catalogue and to this day they are confused with one another. Each gave numbers to the pictures of Ceramics they included but the only Ramié numbers that now mean anything to dealers, collectors and auction houses are the numbers from Alain Ramié’s book. It is an authoritative catalogue raisonne compiled from the records of the Madoura Pottery and includes definitive measurements, descriptions, edition sizes and pictures. Sometimes (but not always) these numbers are referred to as AR numbers. Thus the professional shorthand for this Bull is R 255 or Ramié 255 or AR 255.

Around the time of the record 1990 sale anyone with access to the Alain Ramié catalogue would have known that the Bull was one of an edition of 100. In fact that’s how Sotheby’s identified it in the auction catalogue, but clearly the bidders weren’t aware of or discounted this information. In fact edition size is a problematic fact. After all, it’s not like there are actually 100 of these ceramics available for sale at the time of any given auction — there is only one. It might be years or even decades before another appears for sale (then again, it could be weeks). Of course there’s nothing like a record sale to alert all of the other owners of a similar item that now may be a good time to sell — often gaggles of similar pieces suddenly appear out of the woodwork at the next sale once a record has been achieved.

how Sotheby’s identified it in the auction catalogue, but clearly the bidders weren’t aware of or discounted this information. In fact edition size is a problematic fact. After all, it’s not like there are actually 100 of these ceramics available for sale at the time of any given auction — there is only one. It might be years or even decades before another appears for sale (then again, it could be weeks). Of course there’s nothing like a record sale to alert all of the other owners of a similar item that now may be a good time to sell — often gaggles of similar pieces suddenly appear out of the woodwork at the next sale once a record has been achieved.

In the stock market there are millions of shares, and the “spread” between the bid and ask prices can be a fraction of a penny. However, for thinly traded items the spread can be enormous. In hot markets this may work to the seller’s advantage: you might have multiple bids on your million dollar Miami Beach condo in 2007. But if the buyers suddenly disappear like they did for Florida real estate in 2009 you may have one offer and it might be for $400,000. This is what happened to the artworld when the Japanese “Bubble Economy” burst. The music suddenly stopped, the Japanese buyers disappeared, seemingly from one day to the next. Just as with people holding Collateralized Mortgage Obligations in October 2008, anybody who hadn’t already found a “greater fool” to sell to was stuck.

If the underbidder felt bad about losing the Bull at Sotheby’s October 1990 sale, he probably felt a lot better after the Christie’s sale the next month. And the buyer who bought the Ramié 255 Bull at a 55% discount (perhaps the same underbidder?) may have thought he was a genius. He would have been mistaken. The following year, on November 4, 1991, a Bull sold for $24,200, again at Christie’s in New York, nearly 40% less than the “bargain” November 1990 price. (Of course any dealer with a Bull of his own had immediately raised the price of the one in his shop to at least the $87,000 after the October 1990 Christie’s sale and many never adjusted their price downward — but this will be another post.)

Nearly twenty years later the Picasso Edition Ceramic Bull AR 255 was still changing hands at about the same price it brought in 1991 (one sold at Sotheby’s New York on October 29, 2010 for $25,000).

You would think that the market is more efficient these days, wouldn’t you? That lack of information is no longer an issue, that edition sizes have been discounted in the prices, and that mature markets like the long-standing one for Picasso ceramics can’t suffer from small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.

You would think that the market is more efficient these days, wouldn’t you? That lack of information is no longer an issue, that edition sizes have been discounted in the prices, and that mature markets like the long-standing one for Picasso ceramics can’t suffer from small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.

How then would you explain the Edition Picasso Ceramic Bull that sold on June 25, 2012, just a year and half after a two-decade string of $25,000 – 35,000 sales, for 97,250 British pounds at Christie’s South Kensington, then equal to $151,263?

I’ll try in my next post.

Pablo Picasso Ceramic Editions from the Madoura Pottery

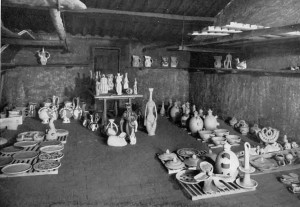

In the summer of 1946 Pablo Picasso visited the ancient city of Vallauris in the South of France. The name Vallauris comes from the Latin “Vallis Auris” – Valley of gold, but the gold here was the rich clay of the area. The town became a pottery center in Roman times, producing the amphorae that wine traditionally was stored in.

Two thousand years later Vallauris was still a pottery center, though the sixty-odd workshops of the town were in depressed economic straights after the Second World War. Picasso, who was soon to move to the South of France, admired some of the local ceramic production in Vallauris and amused himself by decorating a few plates. When he returned a year later and was shown the fired results, he was enchanted. Georges and Suzanne Ramié, owners of the Madoura workshop seized the opportunity to invite him to make himself at home at Madoura, putting all of their artisans at his disposal, even giving him an outbuilding to store his production.

It was a dangerous offer to a man like Picasso, who happily took over the pottery’s entire output. Clearly Madoura couldn’t survive as the personal ceramics studio for Picasso, so it was early on agreed that the Ramiés could produce editions after Picasso’s originals. These “Authentic Replicas” would be sold inexpensively to the tourists, which worked to everyone’s advantage. Picasso could explore this wonderful medium; the tourists could bring home a whole new category of souvenirs from their French vacation; and the local economy would get a much needed boost. Even better for Picasso whose financial success as an artist was the cause of grumbling in the Communist Party which he had recently joined — Picasso could now demonstrate that he was helping labor employment, plus he was making affordable art for the people!

Ultimately Picasso personally decorated over 4,000 ceramics at Madoura, the vast majority of which he kept for himself and which are now in museum collections or still belong to the Picasso family. The artist was also directly involved in the replication by the Madoura artisans of over 600 of his ceramics in editions of between 25 and 500. These were sold at Madoura from 1947 until Picasso’s death in 1973 and what remained continued to be sold until the individual editions sold out. Each ceramic was given an individual reference number in Alain Ramié’s definitive Catalogue Raisonné which everyone now uses for easy identification. The most interesting forms ceased to be available within a few years of their introduction, but Madoura was still marketing leftovers until 2012 when what were said to be the pottery’s “Bon à tirer” collection was sold at Christie’s South Kensington for record prices.

Almost as soon as they became available Picasso ceramics were adored by the public (especially those tourists bringing back Picasso souvenirs). The art establishment, however, was initially convinced Picasso had lost his marbles: the great creator of Cubism was now playing with clay! However, with the 1998 blockbuster exhibition, PICASSO: PAINTER AND SCULPTOR IN CLAY, presented by the Royal Academy of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Picasso ceramics were acknowledged as some of the artist’s most innovative work. Today items that people’s grandparents paid less than $10 for can sell for tens of thousands. The market in fact is more heated — and prices more erratic — than ever before.

With the total number of Edition Picasso Ceramics approaching 120,000 in number, common sense would suggest that the smallest — and therefore the rarest — editions would command the highest prices. However, some ceramics that were made in editions of 25 have sold for much less than fairly common examples from editions of 500. The reasons why might surprise you.

To understand value and quality in this area takes experience and knowledge. I’ve assembled a lot of both as Director for over twenty years of the Jane Kahan Gallery, one of the first and still one of the most important galleries in the world to specialize in this area. In forthcoming posts I’ll share some of what I’ve learned.

Appraising Damaged Fine Art Ceramics

Picasso, Chagall, Miro, Leger, Matisse and other important 20th century artists created ceramic works. It could be a serious mistake for appraisers to use the same percentages to assess loss of value to such fine art pieces as some have suggested for damaged decorative art ceramics and porcelain.

Picasso personally decorated over 4,000 ceramics at the Madoura pottery in the town of Vallauris in the South of France from 1947 to 1972. Most never entered the market. However, editions after 633 of Picasso’s designs were recreated by the artisans at Madoura under the artist’s supervision. These “Edition Picasso” ceramics were at first sold inexpensively to tourists, but such pieces became highly collectible over the years. Edition sizes were anywhere from 25 to 500, bringing the total production to almost 120,000 pieces.

It is thus not uncommon for a personal property appraiser to find Edition Picasso ceramics in an otherwise modest home or estate. Such ceramics, which might have been purchased for less than a hundred dollars in the 1950s or 1960s, can be worth tens of thousands today. Large pieces, which are much rarer than the plates, fish, owls and ashtrays that most tourists brought home, can sell in six figures.

The Jane Kahan Gallery has been dealing in fine art ceramics, especially Edition Picasso pieces, since 1973. We have found that this is not a market that focuses on condition. You do not see Dr. No-type collectors at auctions with black lights and fluoroscopes. Repairs and restorations – as long as they are undetectable to the unaided eye – are rarely discussed in galleries or auction houses, though presumably condition reports would be available if requested. Condition is simply not relevant in the same way it might be with stamps or color field paintings or prints where it is of prime importance. If a piece looks damaged or fiddled with, it’s difficult to sell, either at auction or in galleries. If a ceramic looks perfect, however, then professional buyers (who constitute most of the auction market clientele) treat it as good regardless of what may lurk beneath the surface.

In this litigious society appraisers must therefore be careful with their own opinions, biases and assumptions about condition issues as they relate to fine art ceramics. Regardless of how much an appraiser may believe that condition should affect value, each market has its own realities, which no value formula or guidelines can repeal.

In this litigious society appraisers must therefore be careful with their own opinions, biases and assumptions about condition issues as they relate to fine art ceramics. Regardless of how much an appraiser may believe that condition should affect value, each market has its own realities, which no value formula or guidelines can repeal.

The fact is that perfection was not something that Picasso, nor many other artists, cared about. Picasso cared about the art, he didn’t care about the artifact – a distinction that appraisers reverse to their peril. Picasso never permitted any of his ceramics to be discarded, no matter what their condition issues. There was even a special “mechanic” at Madoura to whom he entrusted the repairs of items that had had firing accidents. We have had at our gallery such a piece, with staples on the back to hold a crack together. This ceramic is pictured in a 1948 magazine with the crack clearly visible. An appraiser inexperienced in the market for fine art ceramics might think this plate is less valuable than a “perfect” piece. Picasso did not think so, nor do many collectors. Nor do we (though we might if it weren’t as attractive and desirable a subject).

In 1951 Chagall created a dinner service as a wedding gift for his daughter. The family used this service at table. Like Picasso’s ceramics, these plates, saucers, cups and platters were soft earthenware. They chipped. A few such pieces entered the marketplace. The chips are as identifiable as fingerprints and make for a compelling provenance. Do they lessen value? We don’t think so. Repairing such damage might even be seen as compromising its integrity.

An appraiser might assume that condition is more important with Edition Picasso ceramics because they were made in quantities, like prints. This is not necessarily the case. However, when an expensive vase falls off the shelf during an earthquake and shatters into pieces, few would argue that there has been a loss. Assessing this loss can present major challenges and traps for appraisers, especially those inexperienced in this sophisticated market.

Consider this parable into which I have incorporated some auction sales and condition issues of a real Edition Picasso ceramic.

Late in 2003, Helene, a fictitious St. Louis appraiser, is called in by a Dr. No (not the same Dr. No who is so scrupulous about condition) to evaluate a large Edition Picasso ceramic vase that accidentally has been broken into pieces. Rather than waiting until the ceramic is repaired and then consulting with experts in this market to determine its post-restoration value, Helene applies percentages suggested in an industry handbook for catastrophic damage to “modern ceramics.” She declares in her loss/damage appraisal that the vase is a total loss, value zero.

The ceramic in question is Oiseaux et poissons, a large and relatively rare vase, number 291 in Alain Ramié’s definitive catalogue raisonne of the Edition Picasso ceramics. A vase from the same edition of 25 had sold at Christie’s London in October of 2002 for $46,590, so Helene puts down this number as the amount of the loss. (The ceramic would probably have been $65,000 or more in a gallery, but Dr. No didn’t have replacement value insurance.)

The ceramic in question is Oiseaux et poissons, a large and relatively rare vase, number 291 in Alain Ramié’s definitive catalogue raisonne of the Edition Picasso ceramics. A vase from the same edition of 25 had sold at Christie’s London in October of 2002 for $46,590, so Helene puts down this number as the amount of the loss. (The ceramic would probably have been $65,000 or more in a gallery, but Dr. No didn’t have replacement value insurance.)

The insurance company takes possession of the shards and has the vase skillfully restored. It then sends it to Sotheby’s in New York, where it goes into a April 2004 sale and sells for $30,000. Already one can see that, by any definition, the “value” of the ceramic is significantly more than zero. In fact Sotheby’s gave it a presale estimate of $40,000 to $60,000, so it is clear that Sotheby’s didn’t seem to care overly that the piece has been repaired (though the words “skillfully restored throughout” are placed into the catalogue entry).

The buyer promptly sends the ceramic to Christie’s London, where it is estimated at ₤20,000 to 30,000 (roughly equivalent to the $40,000 to 60,000 Sotheby’s estimate) and made the cover lot for an October 2004 sale. This time no off-putting mention of restoration is made in the catalogue, but the ceramic does not sell. Note that when Sotheby’s mentioned condition in the catalogue, the piece sold. This time no mention was made, and the piece did not sell.

Condition information is not generally recorded in on-line databases, so potential buyers looking up the auction records for this ceramic wouldn’t have known about the condition of the piece unless they asked for a report from Christies. Few professional buyers of Picasso ceramics are concerned enough to do this, as I have said before. Someone checking the auction databases, however, would have noticed that the last sale of this ceramic was for $30,000, so perhaps the estimate might just have seemed too high for savvy buyers.

In any case Christie’s puts the piece in the April 2005 auction and lowers the estimate to ₤15,000 to 20,000. This seems to do the trick, because the totally restored ceramic sells for ₤31,200 (then $58,646.) to a French dealer, Monsieur Yes (whom I have made up entirely out of whole cloth, as I have the rest of this story, except for the auction

records for this ceramic and its condition issues, which are real). Monsieur Yes has decades of experience with Picasso ceramics. Condition problems are irrelevant to him unless there is a visible problem, which is not the case here (and if there were a visible problem, he would have it repaired). He takes the ceramic back to Paris and subsequently sells it to an American tourist for the equivalent of $125,000 (they get very good retail prices in Paris). He does not disclose that there is restoration because, not having asked for a condition report, he does not know. And even if he did know, in his experience this is not relevant to the value of the ceramic.

The buyer, Mrs. Maybe, proudly ships her prize back home to St. Louis, and early in 2006 she engages Helene the Appraiser to assess the replacement value of her belongings for insurance purposes. Edition Picasso ceramics are numbered, and Helene cannot help but notice that the number of Mrs. Maybe’s Oiseaux et poissons is the same as Dr. No’s. It is the same ceramic.

What dollar value should Helene assign in her appraisal? Two years ago Helene herself had declared this piece worthless. Its fair market auction value of record is $58,646 from the Christie’s sale. Its retail replacement value is the $125,000 for which Mrs. Maybe recently purchased it in Paris – in fact another vase of this type probably could not be found at that point for any price. Similar to Schroedinger’s Cat from quantum physics which found itself in the peculiar position of being both alive and dead at the same time, Mrs. Maybe’s ceramic appears to be simultaneously both worthless and overpriced.

Helene feels ethically bound to disclose the issue of condition of this vase to Mrs. Maybe, but she should think very carefully before she does so. Monsieur Yes does art fairs in New York, Los Angeles and Miami, and he can’t afford to have integrity impugned. He may very well sue if Helene tells Mrs. Maybe that he has sold her a worthless vase for $125,000.

Good luck with your appraisal, Helene.

Copyright @ by Charles Mathes