National Arts Club Lecture: Picasso Ceramics: Fake, Fraud or Genuine?

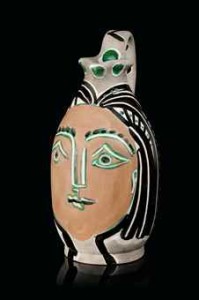

Join Charles Mathes, AAA for a lecture on Picasso Ceramics. Literally tens of thousands of ceramics were replicated at the Madoura Pottery in the South of France after Picasso’s originals. The secondary market for these Picasso ceramic editions is now larger than ever with internet bidders paying record prices based solely on on-line images. While the vast majority of Picasso ceramics in the international marketplace are genuine, it can be a mistake to assume that everything is what it seems to be. This lecture is not the usual survey of what Picasso ceramics are and how they came to be, but instead what they may not be and what they definitely aren’t.

A reception with refreshments will follow the lecture, which will be held in the historic National Arts Club, a National Landmark building and the former home of Governor Samuel Tilden.

Veteran Appraisers Association Certified member Charles Mathes, AAA, was director of a New York City gallery specializing in Modern Art. Now a consultant and advisor, he has handled and appraised hundreds of Picasso ceramics over the course of his career and has written and spoken frequently on the subject.

Veteran Appraisers Association Certified member Charles Mathes, AAA, was director of a New York City gallery specializing in Modern Art. Now a consultant and advisor, he has handled and appraised hundreds of Picasso ceramics over the course of his career and has written and spoken frequently on the subject.

Event Details

Date:

Monday, May 5, 2025

Time:

6-8 PM ET

Location:

The National Arts Club

The Sculpture Court

15 Gramercy Pk S

New York, NY

Price:

In Person (NYC) $20.00 Members

$25.00 Non-Member

Free CASP Student or Associate Candidate

Register for Event

Picasso Ceramics – Originals, Editions and Variants

The term “Picasso Ceramics” generally refers to the pitchers, plates, vases and plaques that were recreated by the artisans at the Madoura pottery in the South of France after ceramics personally decorated by Pablo Picasso. These “authentic replicas” and “original prints” were done in editions of from 25 to 500 and were sold inexpensively to tourists until Japanese demand in the 1980s caused a price explosion. For the past thirty years EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS that might originally have been purchased for under a hundred dollars have sold for tens of thousands.

EDITION PICASSO CERAMIC AR 198 – one of 500 copies – sold at Sotheby’s London 4-10-2017 for $13,194

Because this is the age of “art as investment” people talk about the “Picasso ceramic market.” In order really to have a market for something you need a sufficient supply, a minimum trading volume and reliable information. The New York Stock Exchange for instance, requires member companies to fulfill various reporting requirements, have 1.1 million public shares outstanding and a monthly volume of 100,000. If you add up all the EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS (I once did), the total comes to almost 120,000 pieces. There’s a reliable catalogue raisonné and, while public sales of even the larger editions rarely exceed half a dozen per year, there are enough auction records over the past three decades to give the illusion of a market, albeit a thinly traded and highly inefficient one.

PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINAL – personally decorated by Picasso sold at Sotheby’s in May 2017 for $32,500

But what about ceramics that Picasso personally painted? There were over 4,000 of these, including the prototypes after which the EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS were replicated. The vast majority of such PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS were never offered for sale and are now in museums. Though dealers occasionally get hold of one and a few have made their way to auction, there have been years when it would have been difficult to find a ceramic hand-painted by Picasso for sale anywhere in the world. Nor is there anything approaching a definitive reference, though PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS are discussed in a few books including the catalogue for the 1999 exhibition at the Met, “Picasso – Painter and Sculptor in Clay.” Dealers and auction houses like to call such ceramics “Unique,” perhaps not using the word “Original” so as not to draw attention to the fact that the EDITION PICASSO pieces are what some might call reproductions. However, the term “unique” can be misleading, as we shall shortly see.

In June 2015 Picasso’s granddaughter, Marina, put more than two hundred PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS that she had inherited up for auction at Sotheby’s London. Coincidentally there was a sale of EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS the same day across town at Christies, giving a rare opportunity to compare prices of Picasso’s ORIGINALS versus EDITIONS. But adding a couple hundred of Marina’s ORIGINALS to the few already in circulation didn’t suddenly make this a reliable market. This can be seen from the spread between the sale prices and the estimates, which varied by tens of thousands of dollars. In an efficient market (like the NYSE) the difference between the bid and ask can be a penny.

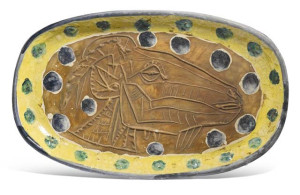

EDITION PICASSO AR 79, one of 300 copies. Between 2014 and 2017 there were more than a dozen sales of this ceramic between about $7,500 and $18,000.

In May 2017 Marina Picasso put more of her inherited pieces up for auction, this time at Sotheby’s in New York. Sotheby’s marketed this batch not as “Picasso ceramics,” but as “Works from the Collection of Marina Picasso.” In fact more than half the sale was comprised of drawings, which also made the three highest prices, but there were also PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS, EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS, as well as another category that most collectors and many dealers are totally unaware of – EDITION PICASSO VARIANTS.

EDITION PICASSO VARIANTS are basically EDITION pieces apart from the official count that were for some reason decorated differently than the ceramics described in Alain Ramié’s definitive “Picasso – Catalogue of the Edited Ceramics.” There is virtually no information available about why such variations were created or how many exist.

PICASSO CERAMIC VARIANT from Marina Picasso Collection brought $30,000 at Sotheby’s NY 18 May 2017

Picasso’s ideas evolved, and he often executed several slightly different versions of a ceramic. Perhaps the VARIANTS were tests, and ultimately a different version was selected for the EDITION PICASSO piece. Another possible explanation is that the artisans at the pottery were just fooling around. Madoura didn’t fire all the pieces of an EDITION at once. A small number were created at a time and another batch was fired only when the existing ones were sold. Maybe there was an extra blank, and someone couldn’t bear to just throw it away. Or maybe Picasso wanted to give a particular ceramic to a friend but the EDITION was closed out, so he just instructed Madoura to make a different, undocumented proof.

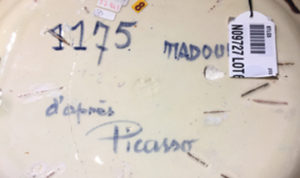

Picasso Dove Variant – reverse.

Whatever the reason for their existence, it’s generally been assumed that EDITION PICASSO VARIANTS were not created by Picasso personally. In the 1950s and 1960s EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS were inexpensive souvenirs; anything that Picasso personally decorated was in a different category entirely and scrupulously documented for the valuable object it was. Thus the VARIANTS that have made their way to auction have been considered mere curiosities and usually sell for prices comparable to the EDITION pieces.

The May 2017 sale of Marina Picasso’s odds and ends, however, has presented a new wrinkle in the status of EDITION PICASSO VARIANTS. The day I went to a viewing only junior people were available at Sotheby’s but I was told that every piece in the sale would come with a certificate from Claude Picasso saying that it was “unique.” Unique in the sense that it was painted personally by Picasso or unique in that it was an undocumented version of the EDITION PICASSO CERAMIC? The junior people weren’t clear, but what’s indisputable is that these ceramics had once belonged to Picasso and were part of the collection that Marina Picasso inherited from her grandfather.

Take a look at the EDITION PICASSO CERAMIC Dove above, AR 79, and the VARIANT from Marina Picasso’s collection. In the auction catalogue Marina Picasso’s Dove is one of the few ceramics in the sale not identified as unique, only as “Painted, glazed and incised ceramic.” It is marked on the reverse “d’apres Picasso” – “d’apres” means “after” in French. The logical conclusion is that it is not from Picasso’s hand; it is simply an EDITION PICASSO VARIANT.

Marina Picasso’s EDITION PICASSO VARIANT Bull’s Profile sold for $62,500

It’s always a good idea to personally inspect an item you wish to buy at auction and to read carefully its catalogue description. Consider Marina Picasso’s Tête de Taureau for example. As with the Dove platter above, the catalogue entry for this Bull’s Profile plaque says nothing about its being unique, just that it’s in reverse in the EDITION piece.

EDITION PICASSO Bull’s Profiles rarely sell for more than $6000.

Yet the ceramic brought $62,500 in the sale, which is curious because there are three different EDITION PICASSO versions of this same Bull’s Profile, adding up to a total of 1000 ceramics, and they generally bring under $6,000 at auction.

Are there other copies of this Bull’s Profile in reverse VARIANT? I have no idea, and as I said before, there is no way to find out. Certainly provenance can add value, but does the fact that Picasso had this VARIANT in his house (over the mantel? in the closet?) make it worth a 1000% premium? If so, why didn’t Marina Picasso’s Dove platter bring ten times the price for that EDITION piece?

Though no claim was made that Picasso personally decorated Marina Picasso’s Dove platter or her Bull’s Profile plaque, the Sotheby’s auction catalogue does give us some new information about VARIANTS, unequivocally stating: “Sometimes the decoration [of empreintes] would be replicated for the editions, but all the examples in the Marina Picasso collection were painted or otherwise decorated by the artist himself.”

Marina Picasso’s Unique Version of an Empreinte Picasso brought $137,000.

“Empreinte originale” – also called “Original Print (or O.P.)”- was a technique whereby a mold reproduced Picasso’s raised structures in the wet clay. The catalogue description of each of such VARIANTS in the Marina Picasso collection calls it “a unique version of the empreinte.” So now we know that Picasso did personally create some VARIANTS, including a “unique version of the empreinte” Tête de Chevre (Goat’s Head), which sold for $137,000. (There are five different EDITION PICASSO versions of similar Goat’s Head empreintes in the catalogue raisonne (Ramié 151 – 155). Marina Picasso’s piece is a VARIANT of AR 154, the only EDITION Goat’s Head that has four Xs.)

EDITION PICASSO CERAMIC AR 154. Goats Heads of the five different types generally bring between about $10,000 and $30,000 at auction

So are there any other “unique” copies of this same Goat’s Head VARIANT? The answer is yes – sort of. Another ceramic much like the one illustrated above came to auction on April 25, 2012, at Phillips de Pury & Co. in New York, where it was even described in the auction catalogue as “a unique variant” and sold for $21,250. The Phillips catalogue reported “There is an extremely similar image of a unique piece in the Marina Picasso Collection (Picasso Keramiek 1985 Museum Het Hruithuis).” Why was the Phillips “unique variant” created? Who decorated it and had the audacity to include nine yellow balls instead of the ten Picasso used in Marina’s ceramic?

EDITION PICASSO VARIANT Goat’s Head brought just $21,250 in a 2012 auction at Phillips

Because different artisans replicated the EDITION PICASSO CERAMICS by hand after Picasso’s ORIGINALS, every EDITION piece is “unique” in that sense. Of necessity all VARIANTS were individually painted, too, and subtle differences in shapes and lines can always be found between two hand-painted recreations. You can see these for yourself if you examine this third VARIANT Goat’s Head that I found advertised on a dealer’s website as a “unique color variant.”

Another Picasso Goat’s Head “unique” variant

If “unique” VARIANTS aren’t enough to drive you crazy, there was actually a fourth category of Picasso Ceramics that were included in the Marina Picasso Sotheby’s May 2017 sale: damaged pieces. Remember that “d’apres Picasso” Dove platter EDITION PICASSO VARIANT? It had a great big crack right down the middle. Was this reason why it didn’t fetch more than about twice the price of the EDITION piece?

Picasso didn’t consider any ceramic a mistake that should be discarded; he believed something could be always be learned and even designated one of the Madoura artisans as his “mechanic” who would repair pieces that had been damaged in the firing. Several PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS in this sale in fact had staples visible on the back to hold cracked pieces together.

A cracked Picasso ceramic showing staples holding it together

Perhaps the VARIANT Dove became part of the Marina Picasso Collection because, no matter who had painted it, Picasso liked it despite the damage and took it home. After all, Picasso was the man who took a little owl with an injured claw home to live with him and Francois Gilot when he first came to Antibes in 1946. It was this owl that in fact inspired a number of his ceramics.

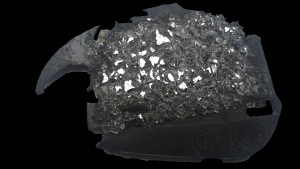

Marina Picasso’s unique Goat’s Head empreinte (it might be clearer to call it a PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINAL – EDITION VARIANT) also had damage clearly visible on the reverse.

Marina Picasso Goat Head damage

So if Picasso didn’t care about damage, should potential buyers? Apparently the buyer of Ms. Picasso’s Goat’s Head VARIANT didn’t, if he or she was even aware that the plate had a crack. These days a lot of auction buyers don’t attend previews or even ask for condition reports, they just look at on-line pictures which rarely focus on a lot’s flaws. Certainly if there are three hundred copies of an EDITION PICASSO CERAMIC and one comes up for sale with a big chunk missing from the rim, people will likely want to wait for a better copy to their collection. However, earthenware ceramics can restored so expertly that even experienced dealers can’t detect any trace of damage by eye, and how many people really demand condition reports on pieces that look perfect? (For a discussion of how restoration can affect value of EDITION pieces, click here.)

With Picasso ORIGINALS, damage may not affect value at all. When casino magnate Steve Wynn put his elbow through Picasso’s painting La Rêve, which hedge fund honcho Steve Cohen had agreed to purchase for $139 million, Wynn sued his insurance company for $54 million in lost value. The suit was settled for an undisclosed amount, but a few years later Cohen turned around and bought the restored La Rêve anyway for $155 million, $16 million more than he was going to pay originally. After all, La Rêve was still a great Picasso, and it wasn’t like Cohen could go out an buy an undamaged version.

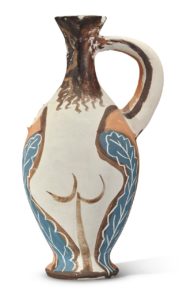

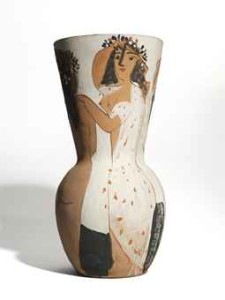

Because of paucity of supply and lack of information, the market for PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINALS is so thin as to be practically non-existent. Consequently damage to such items may in fact present unique opportunities. Consider the top ceramic lot in Sotheby’s May 2017 sale of works from the Collection of Marina Picasso, Vase-femme Avec Bras-Anse, (Woman Vase with Arm Handle)” which brought $250,000.

The catalogue visual of PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINAL, Vase-femme avec un bras-anse

The vase’s rear end

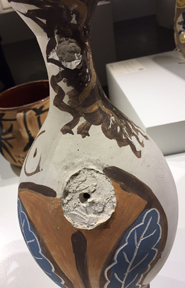

Picasso’s son, Claude, in an essay in “Picasso, Painter and Sculptor in Clay” described how much of a challenge it was for his father to decorate a three dimensional object and how Picasso utilized the forms themselves in creative and whimsical ways – painting the picture of a vase on a vase, turning a handle into a flower, etc. Vase-femme Avec Bras-Anse is a perfect demonstration of how Picasso didn’t merely accept the limitations of shapes but used them to create something even better. However, many potential bidders may have seen only damage if they attended the preview. In the sale room it was evident that the “Arm Handle” had been restored and there had originally been another matching arm on the other side that was now missing entirely!

Picasso Original Repaired Arm

Picasso Original Missing Arm

Despite the damage the ceramic still soared above its $40,000 – $60,000 estimate. I think whoever snapped up this piece still got a tremendous bargain, even if he or she were one of those on-line buyers who had looked only at the pretty pictures in the auction catalogue and fainted when they opened the box. After all, $250,000 is a small price to pay for what is arguably a great PICASSO CERAMIC ORIGINAL. I mean we’re talking about just 1/1000th (all right, 0.00161290322%) of the $155,000,000 that Steve Cohen wound up paying for La Rêve! Who do you think got the better deal?

I think it’s extremely likely that the next time Vase-femme Avec Bras-Anse surfaces it will have both arms intact and no evidence that either of them had ever been anything other than perfect. Even if the new owner is a dealer who wants to make a big profit on the piece there would be no reason to conceal that it had been skillfully restored – a potential buyer will be hard-pressed to find a similar ceramic at any price.

Unique Picasso Ceramics vs. Madoura Editions

The market for Edition Picasso ceramics is hot. The auction prices of some pieces have soared 500% and more from one year (or one sale) to the next.

I’ve discussed the reasons for this explosion of interest before (the Runaway Bull, the Runaway Bull Returns, the High-Flying Owl), reminding people that the Edition Picasso Ceramics were not personally painted by Picasso. Though Picasso decorated over 4,000 ceramics, the Edition Picasso is comprised of some 600 “authentic replicas” recreated after Picasso’s unique prototypes by the artisans at the Madoura pottery in the South of France.

This Edition Picasso “Tête de chèvre de profil” AR 148 sold at Sotheby’s Paris on May 21, 2015, for $19,468.

When people hear about this distinction their initial reaction is often that they don’t want to buy “reproductions,” only originals. Unfortunately original Picasso paintings can cost as much as $179,365,000 at auction. A desirable Edition Picasso ceramic can sell for 1/10,000th of that (the Goat plate illustrated above brought only 1/9,213th of the record painting price, but you get the idea). No wonder these multiples quickly became collectable after their introduction in 1948 when they were sold as inexpensive souvenirs to vacationing tourists. That’s right, Edition Picasso ceramics purchased for fifty dollars in the 1950s are today worth tens of thousands.

So you would figure that the ceramics that Picasso personally decorated would be a lot more valuable than the ones that were replicated, right? Well, yes and no. Yes, they’re worth more. But no, they’re not worth 10,000 times more, or even 1000 times more. Or even 100 times more. Or, often, even 10 times more. And some of them have recently sold for less than Edition pieces.

One reason for this anomaly is the very rarity of Picasso’s “original” ceramics, most which were never commercially available. People equate rarity with value, but prices are determined in the marketplace. Picasso kept the vast majority of the unique pieces for himself and most ended up in museums or with members of the artist’s family. Consequently, the kind of competition that makes prices rise never developed for originals – they rarely came up for sale. However as early as the 1970s the approximately 120,000 ceramics in the Edition Picasso began appearing at auction. If a collector wanted an Edition Picasso ceramic there was a huge selection immediately available, but if he wanted a ceramic that Picasso himself had painted he might wait years before one appeared. The very term “Picasso ceramic” came to mean one of the multiples replicated by the artisans at Madoura.

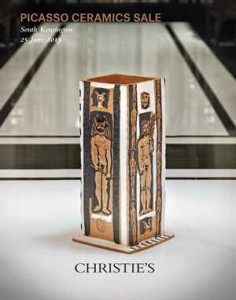

It’s therefore doubly difficult to compare values for unique Picassos and Edition Picasso pieces, since not only do auction results swing wildly from place to place and year to year, there just isn’t much comparable sales data. Because of a rare coincidence, however, we now have a unique opportunity to make such price comparisons. In London on June 25, 2015, Sotheby’s sold a collection owned by Marina Picasso of over 100 ceramics personally painted by her grandfather (Marina is the daughter of Picasso’s son Paulo and his first wife, Olga Khokhlova). On the same day in another part of town there was a dedicated sale of Edition Picasso ceramics – at Christie’s South Kensington, the venue that has accounted for many of the recent record-breaking sale prices.

While comparing apples and oranges is still easier than comparing most of the ceramics in these two sales, some pieces are directly equatable. For instance, take a look at these two pieces:

The one on the left is from the Edition Picasso, Picador et taureau, AR 194, from the edition of 200 (the “AR” number is from Alain Ramié’s definitive catalogue raisonné). The one on the right was entitled Tauromachie in Marina Picasso’s collection, a unique ceramic hand-painted by Picasso — almost certainly the prototype for the Edition piece.

The AR 194 Edition Picasso Picador et taureau plate brought the equivalent of about $10,780 at Christie’s South Kensington. At the Sotheby’s sale across town the comparable unique piece sold for the equivalent of $68,800. Granted that neither one of these ceramics is a great work of art. In fact if you had been at Madoura in 1953 the Edition piece was probably one of the Picasso tsotchkes priced at five or ten bucks. But if you use these two ceramics as a guide, a Picasso “original” is worth 6.38 times more than the Edition Picasso piece.

However, another pair of ceramics tell a different story:

In the Christie’s sale, the AR 296 Edition Picasso ceramic, pictured on the left, sold for $27,440 (I’m using the auction houses’ conversions to translate all of these prices from pounds to dollars). The one of the right, one of Marina Picasso’s unique pieces, sold for $94,354 at Sotheby’s. The market — as well as your eyeballs — might suggest that these ceramics are “better” than the Picador plates. However, using these vases as a guide, a Picasso “original” is worth only 3.43 times more than the copy. Why does a “better” original bring a smaller multiple?

In the Christie’s sale, the AR 296 Edition Picasso ceramic, pictured on the left, sold for $27,440 (I’m using the auction houses’ conversions to translate all of these prices from pounds to dollars). The one of the right, one of Marina Picasso’s unique pieces, sold for $94,354 at Sotheby’s. The market — as well as your eyeballs — might suggest that these ceramics are “better” than the Picador plates. However, using these vases as a guide, a Picasso “original” is worth only 3.43 times more than the copy. Why does a “better” original bring a smaller multiple?

The most expensive piece in Sotheby’s sale of Marina Picasso’s ceramics, by far, was described as a vase but seems more of a sculpture than the usual shapes and plates in the Edition Picasso. It sold for $762,698 and is pictured at the top of this page. No Edition Picasso ceramic is even remotely comparable to this piece. The top lot in the Christie’s sale was Femme du Barbu (the Bearded Man’s Wife), AR 193, which sold for $163,856. Using these two ceramics as a guide you might conclude that the best Picasso original is worth 4.65 times more than the best Edition Picasso multiple.

Of course it is worth noting that Femme du Barbu is hardly among the “best” Edition Picasso ceramics. For starters it’s an edition of 500, the largest edition size made. I’ve found 16 other sales of this ceramic since 2013 with an average sale price of about $30,000 (until the Madoura sale in 2012 they brought much less). Femme du Barbu was estimated in the Christie’s catalogue for about $19,000 – $28,000. In short, it’s a fairly large, very common ceramic, and it’s whimsical and fun. But you can say the same about many, many other pieces.

So in the interest of fairness let’s look at what actually is considered to be the “best” Edition Picasso ceramic because of its scale, rarity, beauty and renown: the Grand Vase, AR 116. This ceramic is over ten inches larger than Femme du Barbu, it’s from an edition of just 25 (the smallest produced), it is pictured on the cover of the Alain Ramié’s catalogue raisonné and in a famous photograph of Picasso by Henri Cartier-Bresson. One of these pieces made the auction record for an Edition Picasso ceramic: $1,144,268 at the much hyped “Madoura” sale in 2012. Another brought $1,080,221 in 2014. Thus using the Grand Vase as a guide, the best “original” Picasso ceramic in Marina Picasso’s collection was worth less than the best Edition Picasso piece!

Prototype for Picasso “Grand Vase” AR 116 which brought a record $1.5 million. One of the 25 Madoura Edition Picasso copies brought $1.14 million.

If you want to get picky, at $762,698 Marina Picasso’s unique vase pictured above isn’t the “best” unique Picasso ceramic ever to sell at auction, at least in terms of price. Ironically that honor belongs to Picasso’s prototype for the same Grand Vase that set the record for most expensive Edition Picasso ceramic. This prototype sold in 2013 at Christie’s in London for $1,534,557. In other words, the original sold for only 1.5 times more than the copy.

Clearly something is screwy here. Either Edition Picasso ceramics are overpriced, unique Picasso ceramics are underpriced, or a combination of both. To say nothing of the possibility that the entire art market may presently be in the same kind of mania that precedes stock market crashes (and the fact that it’s silly to try to draw conclusions from individual sales in thinly traded, inefficient markets).

Regardless of whether an entire market is elevated or depressed, however, certain ratios should be constant unless there is a fundamental paradigm shift as there was in the 1970s and 1980s due to the influx of Japanese buyers. In Western culture, oil painting is the most important fine art; ceramics are less important. In Asia it’s just the opposite. When the Japanese entered the market, they were willing to pay vastly higher prices for ceramics than anyone ever had before. When they stopped buying at the beginning of the 1990s, prices crashed.

Unique Picasso Goat plate from Marina Picasso’s collection sold at Sotheby’s in June 2015 for $176,914

Let’s return for a moment to that $179 million record-price Picasso painting, and the fact that you can get a fine Edition Picasso ceramic for about 1/10,000th of that. The Tête de chèvre (AR 148) platter from the edition of 100 pictured at the top of this page is an example of such a bargain at a sale price of $19,468. If you believe in numerology (and the metric system) you’ll be interested to learn that Picasso’s probable prototype for Tête de chèvre sold for $176,914 in the Marina Picasso sale at Sotheby’s, about ten times more than its Edition Picasso equivalent but close to 1/1,000th of the record-price Picasso painting.

So, how much more should unique Picasso ceramics be worth than comparable Edition Picasso pieces? If the answer is 1000 times, then the Grand Vase prototype should have brought at least a BILLION dollars — 1,000 times the $1+ million that the two Edition Picasso Grand Vases have recently sold for. If the answer is 100 times, then the best originals should be somewhere between $50 and $100 million — 100 times the $500,000+ prices that many other Edition Picasso Grand Vases have brought at auction. If it’s a mere 10 times, as the the two  Goat plates would seem to suggest, then best original Picasso ceramics should sell in the $10,000,000 range. If the other examples compared above are better guides, then the best unique pieces should be $6,380,000 or $3,430,000, 0r $4,650,000 — in all cases significantly more than they have actually been selling for. To my mind the buyer of the beautiful Picasso at the top of the page got a steal.

Goat plates would seem to suggest, then best original Picasso ceramics should sell in the $10,000,000 range. If the other examples compared above are better guides, then the best unique pieces should be $6,380,000 or $3,430,000, 0r $4,650,000 — in all cases significantly more than they have actually been selling for. To my mind the buyer of the beautiful Picasso at the top of the page got a steal.

Clearly Christie’s believed that the “best” Edition Picasso ceramic in their sale of June 25, 2015, was Personnages et Têtes AR 242. At 22 inches tall, not only was it the largest piece in the sale, it was one of only 25, the smallest edition size produced at Madoura. It was pictured on the cover of the catalogue and brought the second highest price in the sale (after the outlier Femme du Barbu ), selling for $145,040 — over twice its low estimate ($62 ,000 – $92,000). Yet more than half of the unique Picasso ceramics from Marina Picasso’s collection at Sotheby’s sold for less than the cost of this Edition Picasso multiple. Granted that the originals were smaller in size and arguably less interesting than Personnages et Têtes, but they were actually from the artist’s hand, not “authentic replicas.”

Which would you rather own?

Repent! The End (of the Art Bubble) is Nigh!

Laurence Fink, chairman of the world’s biggest asset management firm, Blackrock, said recently that contemporary art, along with apartments in places like New York and London, had supplanted gold as the world’s top store of value. This is an ominous signal for the art world.

The concept of “store of value” is one that acquires relevance in direct proportion to your wealth. That $1,000,000 you’ve put under your mattress will be worth only about $550,000 twenty years from now figuring 3% inflation. Buy a Manhattan apartment with the money (you can probably afford an okay studio), chances are you won’t take such a haircut. Invest in the next Apple and maybe you’ll do a lot better (invest in the next Enron, maybe you’ll end up with nada).

But let’s say you’re a billionaire. Forbes Magazine says that there are 1,826 such people in the world in 2015, and their problem is literally a thousand times worse than yours (a billion is a thousand million). How can you efficiently store immense wealth so that it remains safe and keeps its value? It won’t fit under the mattress. In fact it was this sort of dilemma that led to the invention of money, an abstraction that could be used to stand in for the actual wealth it represented, whether that wealth be land, goats or wives.

But let’s say you’re a billionaire. Forbes Magazine says that there are 1,826 such people in the world in 2015, and their problem is literally a thousand times worse than yours (a billion is a thousand million). How can you efficiently store immense wealth so that it remains safe and keeps its value? It won’t fit under the mattress. In fact it was this sort of dilemma that led to the invention of money, an abstraction that could be used to stand in for the actual wealth it represented, whether that wealth be land, goats or wives.

The only essential criterion for something to become money is that everyone agrees that it’s money. Over the centuries some abstractions that people have agreed can be money are shells, beads, axes, gigantic donut-shaped carved limestone wheels, woodpecker scalps, bitcoins and of course printed slips of paper bearing pictures of dead Presidents.

Gold is a particularly successful abstraction for money, though it has no real “intrinsic” value. You can get milk from a goat, you grow vegetables on land, and wives can demonstrate value in numerous ways, but gold just sits there, weighing a lot and not producing anything. But gold is a unique material that is easily worked into beautiful articles that don’t deteriorate over time. It is naturally rare. For millennia people have been willing to trade goats and wives for gold. You’d be betting against history if you thought that demand for it, whether rational or not, was suddenly going to evaporate.

Demand for other abstract stand-ins for wealth like woodpecker scalps (and paper money issued by profligate countries) is not so stable. Which brings us to art.

Art, like gold, doesn’t produce anything but can be beautiful to look at and its natural supply is limited. While many artists may toil at their craft the output of only a vanishingly small minority is ever transformed from mere decorations into a store of significant value.

Exceptionally talented artists who worked for decades to hone their skills used to be the ones to whom cultures awarded fame and wealth. But starting in the late 19th century, artists began to achieve greatness because they broke the rules. Vincent Van Gogh never sold a painting in his entire life, but our culture came to consensus years ago that his work was revolutionary, a turning point in history. The Impressionists broke the rules, too. Though many of their contemporaries thought Impressionism was ridiculous, today we see paintings by Monet, Renoir and others as both valuable and beautiful. But both value and beauty are relative notions that change as societies change (Lillian Russell was considered one of the most beautiful women in the world in the 1890s; today she would be considered plus-sized). So do concepts of wealth.

Exceptionally talented artists who worked for decades to hone their skills used to be the ones to whom cultures awarded fame and wealth. But starting in the late 19th century, artists began to achieve greatness because they broke the rules. Vincent Van Gogh never sold a painting in his entire life, but our culture came to consensus years ago that his work was revolutionary, a turning point in history. The Impressionists broke the rules, too. Though many of their contemporaries thought Impressionism was ridiculous, today we see paintings by Monet, Renoir and others as both valuable and beautiful. But both value and beauty are relative notions that change as societies change (Lillian Russell was considered one of the most beautiful women in the world in the 1890s; today she would be considered plus-sized). So do concepts of wealth.

Take one of the most famous artworks in the world: Picasso’s “La Reve.” Casino magnate Steve Wynn bought this painting at auction in 2001 for about $60 million — the previous owner had gotten it auction in 1997 for $48 million. Wynn reportedly had agreed to sell it to hedge fund giant Steven A. Cohen for $139 million five years later. The painting would have thus become the most expensive ever sold, only Mr. Wynn put his elbow through the canvas and the deal was called off. Wynn collected millions of dollars in insurance because of the damage, and then still sold it to Cohen for $155 million in 2013 — a good investment any way you look at it and worth “a fortune” every time it traded hands.

Yet when Victor and Sally Ganz originally purchased “La Reve” in 1941, the price was $7,000, which was considered to be a fortune to spend on art in those days. It is equivalent of about $112,000 in today’s money. Some would still consider $112,000 a fortune, but certainly not the 17,685 people in the United States who filed tax returns in 2012 showing annual income of over $10,000,000 according to the IRS. Approximately 128,200 individuals worldwide have a net worth in excess of $50 million according to Credit Suisse.

So where can all these people store all that kind of value? Real (literally) estate entails significant carrying costs. The 18th floor of the Sherry Netherlands Hotel, for instance, has been marked down $30 million to a more reasonable $95 million, but the monthly maintenance fee is $60,000. And real estate is not particularly portable, unlike paintings which you can just carry back to Russia or China on your private jet.

In a world where the top 1% of the world’s population control over 50% of the wealth, an abstraction like Art would seem like a wonderful solution. Certainly it was for the billionaire Qatari who just spent $179 million for the current record breaking Picasso. However, the merely rich, too, need something to decorate their humble seven-figure abodes and show people how rich and clever they are. This demand has resulted in an ever-increasing need for more art. Luckily Andy Warhol practically single-handedly created a new category called called Contemporary Art when he broke all the rules and put a frame around a can of soup. Suddenly, anything could be art, thus conveniently increasing its supply exponentially. Over the past decades other would-be revolutionaries have become rich and famous by putting frames around everything from chicken-scratch doodles (Cy Twombley) and comic strips (Roy Lichtenstein) to dead animals floating in tanks of formaldehyde (Damian Hirst) and West Highland white terriers (Jeff Koons).

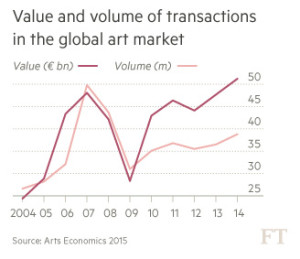

One of the lessons of history is that when governments go crazy printing money it often loses its value. Today it is not only governments who can print money, it is a small number of artists whom art dealers and the super rich have randomly anointed. Anything these artists produce magically becomes money: piles of candy, messy unmade beds, even pieces of shit. This Contemporary Art can be produced as fast as you can say “art asset investments.” However, even as supply increases, demand has begun to break down except at the highest level. Fewer and fewer people are exchanging more and more wealth for a dwindling number of these abstractions, as a graph compiled by the Financial Times clearly shows.

It is very dangerous when people lose sight of the difference between wealth and the abstractions that stand in for wealth. Natural pearls were once a formidable abstract stand-in for wealth. In 1917 the jeweler Cartier traded a double-stranded pearl necklace then worth over a million dollars for its landmark home, the Neo-Renaissance building at 53rd and Fifth Avenue. The Cartier building today is probably “worth” more than that record-breaking Picasso. The necklace was sold at auction in 1957 for $151,000.

The present attitude toward art has evolved so slowly that it must seem like a totally reasonable stand-in for real wealth to the 1% (whom the other 99% believe don’t know the value of a dollar). It probably seemed just as reasonable that certain tulip bulbs were worth more than country estates in 17th Century Holland. Or that companies which never earned a nickel were “worth” more than General Electric during the Dot.com years. Art is no longer beautiful and/or meaningful creations by people with unique talent who have worked years honing their craft, it is now practically defined as rule breaking in an area that no longer has any rules. No one has put a frame around a pile of ping pong balls? Quick, call the Whitney!

The present attitude toward art has evolved so slowly that it must seem like a totally reasonable stand-in for real wealth to the 1% (whom the other 99% believe don’t know the value of a dollar). It probably seemed just as reasonable that certain tulip bulbs were worth more than country estates in 17th Century Holland. Or that companies which never earned a nickel were “worth” more than General Electric during the Dot.com years. Art is no longer beautiful and/or meaningful creations by people with unique talent who have worked years honing their craft, it is now practically defined as rule breaking in an area that no longer has any rules. No one has put a frame around a pile of ping pong balls? Quick, call the Whitney!

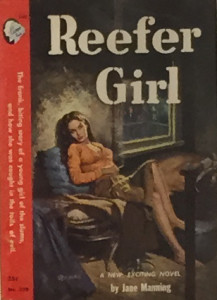

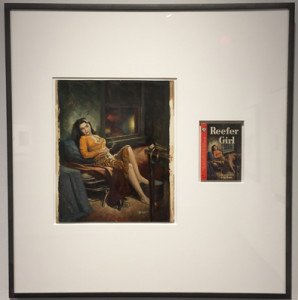

“Appropriation artist” Richard Prince is a just one example of what I call “Emperor’s New Clothes Art” — as in Hans Christian Andersen’s classic story. The rule Price broke was the Eighth Commandment: Thou Shalt Not Steal. For one of his early successes Prince photographed and retouched other’s people photographs. Another triumph are “his” Nurse Paintings where Prince scanned book covers, transferred the images to canvas with an inkject printer, and then added some acrylic paint. Recently he was in the news for reproducing people’s Instagram posts without notice or permission and selling them for $90,000.

Prince is handled by the Gagosian Gallery, one of the important galleries in the world, where his oxymoronically entitled show “Original” can be seen until June 20, 2015. Over the years Prince purchased the original cover art for the pulp paperback books that he collects. Such paintings, many by unknown artists, often sell for less than $1000 and you can find vintage paperbacks on Ebay for a few bucks. For the Gagosian show Prince simply framed the paperback along with the original cover art. The result actually ends up looking pretty cool until you find out that the prices are in the $250,000 range. That’s right: people are spending $250,000 for a framing job. And I’m sure they’ll tell you that you’re an unsophisticated idiot if you don’t see how important and wonderful this latest fashion is.

Prince is handled by the Gagosian Gallery, one of the important galleries in the world, where his oxymoronically entitled show “Original” can be seen until June 20, 2015. Over the years Prince purchased the original cover art for the pulp paperback books that he collects. Such paintings, many by unknown artists, often sell for less than $1000 and you can find vintage paperbacks on Ebay for a few bucks. For the Gagosian show Prince simply framed the paperback along with the original cover art. The result actually ends up looking pretty cool until you find out that the prices are in the $250,000 range. That’s right: people are spending $250,000 for a framing job. And I’m sure they’ll tell you that you’re an unsophisticated idiot if you don’t see how important and wonderful this latest fashion is.

I’m sorry, but the Emperor has no clothes.

Bubbles end when price and value diverge overwhelmingly, though it’s always been been difficult to call a top  (economist John Maynard Keynes is said to have remarked that the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent). There more than a few billionaires who have made their fortunes by betting on irrationality, but at some point the music stops. Today’s art market is fueled by huge amounts of international money from people who are speculating in a rigged market that what they buy today will garner them the same status (and profits) as others of their financial station have enjoyed for years.

(economist John Maynard Keynes is said to have remarked that the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent). There more than a few billionaires who have made their fortunes by betting on irrationality, but at some point the music stops. Today’s art market is fueled by huge amounts of international money from people who are speculating in a rigged market that what they buy today will garner them the same status (and profits) as others of their financial station have enjoyed for years.

It will end badly.

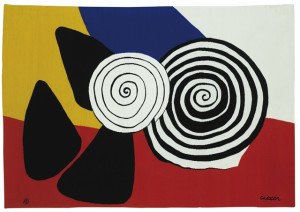

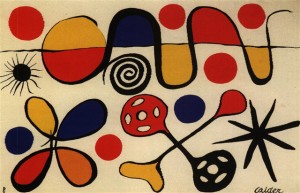

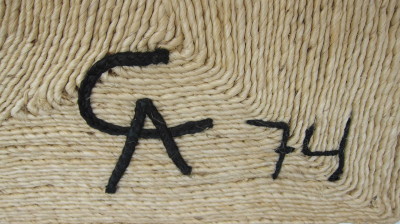

All Calder Tapestries Are Not Created Equal

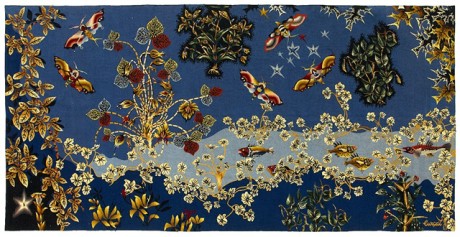

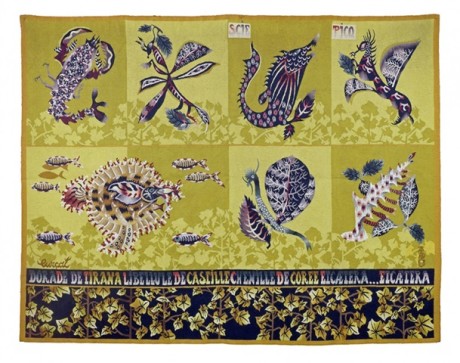

Alexander Calder (American, 1898 – 1976) may be best known for his stabliles and hanging mobiles but he also worked in almost every medium imaginable — paintings, prints, jewelry, stage sets and wire sculpture — he even decorated airplanes.

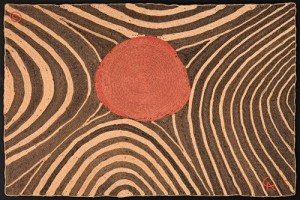

Beginning in the 1960s Calder aligned himself with important French weavers, most notably Pinton, which recreated his designs in fine art tapestry. Calder’s work was graphic, simple and perfectly suited to the medium, which made it both highly desirable to art buyers and profitable for the tapestry ateliers. Ultimately there were more tapestries by Calder than by nearly any other well-known artist.

“Les Passoires,” the most expensive Calder recorded at auction sold in 2007 for the equivalent of $77,810 without premium. Six years later in 2013 another copy from the edition sold for $5,000 less — premium included.

Some dealers now are asking over a hundred thousand dollars for Calder Aubusson tapestries, though they certainly can be found for less — not just because of the number available (there were over 60 different Calder designs made into small-edition Aubussons), but because there is a lot of confusion in the market place about this lesser-known medium. These days people use the word “tapestry” to refer to any textile that can be hung on a wall for decoration. You can take a blanket off your bed, tack it up over the window and call it a tapestry — no Vocabulary Police will arrive to arrest you. Consequently some types of Calder “tapestries” are worth a lot more than others.

There are basically five types of what people call “Calder tapestries”: 1) Aubussons; 2) Bicentennial Aubussons; 3) Natural Fiber Wall Hangings; 4) Pile rugs and carpets (tapis); and 5) Problematic Items

CALDER AUBUSSON TAPESTRIES

The tradition of weaving textiles goes back to ancient times. Horizontal stands of wool (or other material) called weft threads are passed between vertical warp strands that are affixed to a wooden frame called a “loom.” Colors are changed to create patterns or images. The resulting textile are called tapestries. The “Sun King” of France, Louis XIV, set up Manufactures Royales like the Gobelins to weave tapestries in this tradition for his palace at Versailles, and French tapestries woven in this manner are generically called “Aubussons.” Aubusson is actually a town in central France, which Louis declared a “Manufacture Royale” in 1665. Its output, and the output of ateliers in its sister city of Felletin (declared a Manufacture Royale in 1689) has always been commercially available and tightly controlled for quality.

A smaller ( 66 x 49 inches) and less colorful Calder Aubusson sold in November 2013 at a more obscure French auction for a hammer price of about $4,000.

It can take a skilled weaver a month to create a square meter of a fine Aubusson, so these French textiles — handwoven in the most famous tapestry ateliers in the world — have always had intrinsic value. Supply and demand has resulted in people willing to a premium above the weaving costs for images by important artists.

Some of the differences in pricing of Calder Aubussons has to do with basic considerations such as size. Large tapestries tend to cost more than small ones since their original retail cost was higher because they took longer to weave. Sometimes, however, very large tapestries can be difficult to resell because there are fewer potential buyers with giant walls. This is one factor that makes auction prices for tapestries so deceptive. There is very definitely a “sweet spot” in terms of size — if it’s too big or too small fewer people will bid.

Quality is also a factor. Buyers are sometimes more attracted to busier, more colorful images, but sometimes art can be too busy and too colorful. Or too quiet and not colorful enough. It’s a matter of taste and trends. Calder is much more popular now than he was twenty five years ago and Calder Aubussons are very much in demand.

CALDER BICENTENNIAL AUBUSSONS

1976 was the two hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the Bi-Centennial. As part of the celebration a special series of 6 different Calder Aubussons was commissioned. Aubusson tapestries are limited in France to editions of no more than 6 with two authorized proofs — a maximum total of eight pieces. What made the Calder Bicentennial tapestries special is that the French government in the spirit of celebration allowed 200 sets to be woven. It was a magnanimous gesture — and an optimistic one.

eight pieces. What made the Calder Bicentennial tapestries special is that the French government in the spirit of celebration allowed 200 sets to be woven. It was a magnanimous gesture — and an optimistic one.

Only about 45 sets were actually ever made, which leads to confusion about supply in both directions. People have assumed that since the Bicentennial tapestries are Aubussons they must be editions of only six. Others assume that there were actually 200 tapestries made of each design. Whether 8, 45 or 200 were made, demand is actually more important in the pricing of tapestries (and most art) than supply. The Bi-Centennial Calder Aubussons are physically smaller and the designs generally less complex and graphically interesting than the most desirable Aubussons, so there is less demand and prices usually are significantly lower.

Bottom line: Depending upon the asking price, Calder Bicentennial tapestries may or may not be the bargains they seem to be.

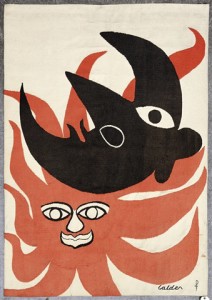

CALDER JUTE/MAGUEY FIBER WALL HANGINGS

Perhaps the most confusion when people talk about Calder tapestries comes from the series of mats that were created as part of a charitable relief program to help victims of a devastating 1972 earthquake in Nicaragua. Kitty Meyer, a New York socialite, had brought Calder a thank you gift of a hammock braided by the artisans in the village of Masaya employing a centuries-old technique. The material used was not the fine wool employed by the ateliers of Aubusson and other famous tapestry centers, but natural vegetable fibers that could be spun into strong, coarse threads. The material may be identified as being Jute, Hemp, Maguey, Raffia or even rope. Calder was intrigued by the process. After collaborating on some hammocks, he ultimately agreed to let artisans in Nicaragua and Guatemala similarly execute 14 of his designs as mats in editions of 100 (the craftsmen were paid four times their usual wage plus given the materials gratis).

Perhaps the most confusion when people talk about Calder tapestries comes from the series of mats that were created as part of a charitable relief program to help victims of a devastating 1972 earthquake in Nicaragua. Kitty Meyer, a New York socialite, had brought Calder a thank you gift of a hammock braided by the artisans in the village of Masaya employing a centuries-old technique. The material used was not the fine wool employed by the ateliers of Aubusson and other famous tapestry centers, but natural vegetable fibers that could be spun into strong, coarse threads. The material may be identified as being Jute, Hemp, Maguey, Raffia or even rope. Calder was intrigued by the process. After collaborating on some hammocks, he ultimately agreed to let artisans in Nicaragua and Guatemala similarly execute 14 of his designs as mats in editions of 100 (the craftsmen were paid four times their usual wage plus given the materials gratis).

Part of the problem with these mats (originally people put them on the floors of their rec rooms and porches) is that some of the designs were the same ones that had been used for Aubusson tapestries. If you looked at one of these mats next to an Aubusson tapestry and felt the materials, the difference in quality would be immediately apparent. However, if you had no familiarity with tapestries and wanted to get an idea of what your Calder maguey fiber mat might be worth, you might turn up a picture (and a price tag) of the Calder Aubusson with the same image and think you had hit the jackpot. And once prices for these mats escalated into the thousands, galleries bought them from people who had them on their floors and sold them as tapestries to people who put them up on their walls.

Part of the problem with these mats (originally people put them on the floors of their rec rooms and porches) is that some of the designs were the same ones that had been used for Aubusson tapestries. If you looked at one of these mats next to an Aubusson tapestry and felt the materials, the difference in quality would be immediately apparent. However, if you had no familiarity with tapestries and wanted to get an idea of what your Calder maguey fiber mat might be worth, you might turn up a picture (and a price tag) of the Calder Aubusson with the same image and think you had hit the jackpot. And once prices for these mats escalated into the thousands, galleries bought them from people who had them on their floors and sold them as tapestries to people who put them up on their walls.

Perhaps a bigger problem is that the Calder Foundation pictures several of these fibre hammocks and mats in the “Misattributed” section of their website, maintaining that Kitty Meyer was not authorized to make editions and that duplicate numbered pieces have been brought to their attention.

It’s comforting to think that every art professional is an expert who knows everything about everything, but misinformation percolates into world through innocence more often than deception. Though it has become rarer in recent years, you can still find these Calder fiber mats misidentified in both galleries and auction houses. This becomes an even more difficult problem with online auctions. It can be very hard to tell whether a “tapestry” is a maguey fiber mat or an Aubusson from a little tiny picture. Also, more and more retail sellers are turning to auction format because of the public perception that they will invariable get things cheaper at auction. Even if a Calder “tapestry” has been identified as one of these wall-hanging and not an Aubusson, the estimate from some online auctions may in fact reflect a retail price range, not an auction value.

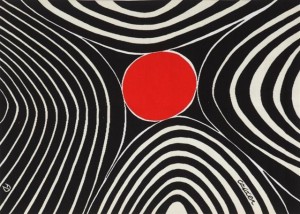

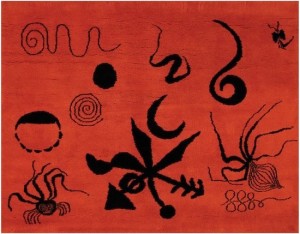

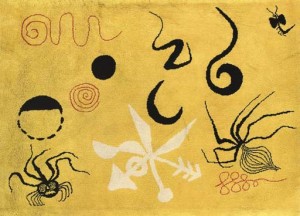

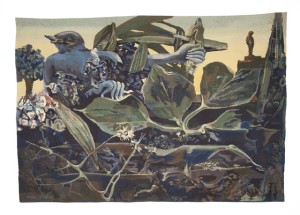

Take a look at the images below. The top piece is the Calder Aubusson tapestry Sillons Noirs from the edition of 6. The visual beneath is a maguey fiber mat sometimes identified as Zebra, an edition of 100.

This is a case where the confusion could have benefited a knowledgeable buyer. Over the past five years one Sillons Noirs Aubusson sold for about $12,000 and another passed at about $13,000, albeit in obscure French sales. The apparently faded maguey fiber wall hanging at the bottom — sold (albeit in Australia) for over $15,000. Another copy of this very same hanging sold at Phillips in London January 22, 2015, for about $3,000.

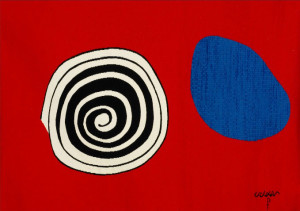

CALDER RUGS AND CARPETS (TAPIS)

The second biggest source of confusion when it comes to Calder tapestries are pile carpets and rugs, which the French call “tapis.” These are very graphic and people (including Calder himself) hang them on walls, so inevitably they are called tapestries.

The second biggest source of confusion when it comes to Calder tapestries are pile carpets and rugs, which the French call “tapis.” These are very graphic and people (including Calder himself) hang them on walls, so inevitably they are called tapestries.

In the book, Calder’s Universe, which was published in conjunction with the Whitney Museum’s 1976 Calder Retrospective, several rugs are pictured, some hooked and knotted by Louisa Calder, the artist’s wife, others by apparent friends of the family. These are identified as never being available for sale, only for personal use. In that anyone who knows how to make a rug (including commercial manufacturers who haven’t heard about artist’s rights) could conceivably make one after a Calder design, provenance can play an important part in determining whether a Calder rug is even legal.

There were two or three Calder tapis that were legitimately created by Marie Cuttoli, a friend of many artists including Picasso. Cuttoli had rugs made after Calder paintings she owned. Hand-knotted in India, these were originally sold in galleries both in Europe and the United States, but always for prices much less than Aubussons. While people generally assume that these were limited editions there were probably dozens created. And, as can be seen from the visuals, color seems to have been a matter of debate.

PROBLEMATIC CALDER TAPESTRIES

Problematic doesn’t necessarily mean illegitimate, it simply means there are problems. One such problem is how to figure out whether a price is a bargain or an outrage without comparable sales data. The less known a work is, the bigger the problem. A legitimate Calder tapestry was actually woven of goat hair in the African country of Lesotho. Good luck in figuring out what is a fair price for one (and such an item might be hard to r esell if you are thinking of buying it as an investment).

esell if you are thinking of buying it as an investment).

As explained above, Calder rugs and carpets can be problematic because, with the exception of the Marie Cuttoli pieces, there is scant information about who created Calder tapis, when they were made and whether they were authorized.

The biggest problems come from items that were created without permission whether innocently (a lot of little old ladies who admire Calder know how to hook rugs) or perhaps deliberately created to deceive. Take a look at the tapestry above. It appears to be a weaving of “Les Masques” a very good Calder Aubusson, one of which is owned by the Whitney Museum and is illustrated in Calder’s Universe.

If you saw this image in a catalogue or on a gallery’s website and were in the market for a Calder tapestry, this would seem to be a good choice, even at a high price. But you might be in for a surprise. Only when you received the tapestry will you notice that it is not a tapestry at all, it is a pile carpet.

I have no idea how this pile rug after the Calder Aubusson came to be made or who created it. And this isn’t the only Calder rug pretending to be an Aubusson that I’ve seen. Perhaps they might even have been authorized in some way, but I wouldn’t want to be the one who shelled out a lot of money with the hope that the Calder Foundation knew all about it.

The bottom line is that buying tapestries can be just as confusing and potentially treacherous as buying any kind of art. It’s important to understand what you’re doing or to be dealing with someone who does. And it may not be wise to rely on a seller’s expertise alone: someone who has something to sell always has a built-in conflict of interest when it comes to what’s best for the buyer.

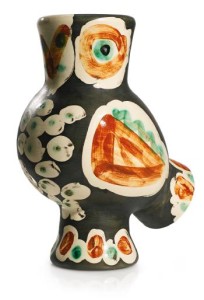

Value Mysteries: Picasso Ceramic Owls

In 1946 Picasso was staying near Antibes in the South of France and decorating the walls of what would become the Musée Picasso. A small owl with an injured claw that had been found in a corner ended up living with him and his lover, Francois Gilot. According to Gilot in her book “Life With Picasso” the owl was an ill-tempered creature who smelled awful and ate only mice. The owl would snort at Picasso and bite his fingers; Picasso would reply with a string of obscenities just to show the bird who was the most ill-tempered. Clearly bad manners were the way to Picasso’s heart for not only did he do a number of paintings, drawings and prints of owls, he created numerous ceramics.

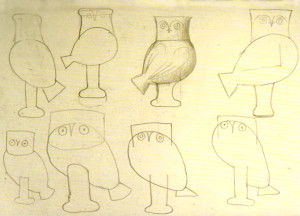

While it is true that Picasso didn’t create most of the ceramic shapes that he decorated at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris (though he did manipulate many of the forms — bent them to his will, if you will), it was not until after the artist’s death did sketches come to light that proved Picasso had in fact executed designs for ceramics around the time the little owl was regurgitating hairballs around the house.

While it is true that Picasso didn’t create most of the ceramic shapes that he decorated at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris (though he did manipulate many of the forms — bent them to his will, if you will), it was not until after the artist’s death did sketches come to light that proved Picasso had in fact executed designs for ceramics around the time the little owl was regurgitating hairballs around the house.

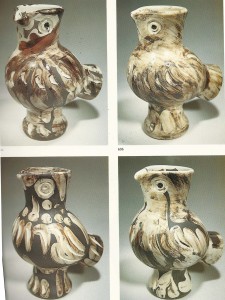

Take a look at five ceramics below that were created at Madoura in 1951. One of them was painted personally by Picasso. The others were painted by the artisans at the pottery after Picasso’s original, what are called “authentic replicas” in the Ramié catalogue raisonne and what are commonly known as Edition Picasso Ceramics. Can you tell which is the one painted by the artist?

This isn’t the value mystery by the way, although Picasso’s unique prototypes usually command prices at least ten times higher than the editions. We’ll get to the value mystery shortly. First, however, it will be useful to understand how relatively common this owl shape was in the entire set of 633 Picasso ceramics that were made into editions.

This isn’t the value mystery by the way, although Picasso’s unique prototypes usually command prices at least ten times higher than the editions. We’ll get to the value mystery shortly. First, however, it will be useful to understand how relatively common this owl shape was in the entire set of 633 Picasso ceramics that were made into editions.

Of the edition owls above one was of 500 (Picasso ceramics were made in editions of between 25 and 500), so it is not particular rare. The other three were from editions of 300, so already in 1951 there were 1400 owls of this shape flying out of Madoura. You might think that there were really 1401 counting the one that is Picasso’s unique piece, but you would be wrong. In addition to the unique piece (the fourth in the lineup above) which was not made into an edition, there were prototypes for the four other owls that were replicated plus, undoubtedly, other paintings by the artist of this shape. The essence of Picasso’s genius was his being able to tap into a virtually inexhaustible creativity. Once the artisans at the Madoura pottery had created Picasso’s owl shape in ceramic they would have given him some fired pieces which he would have begun decorating. It was not unusual for Picasso to paint a dozen ceramics in a day or more. Altogether he painted over 4000 pieces at Madoura, only 633 of which were made into editions.

There were other owl shapes decorated by Picasso but this, his own, clearly remained one of Picasso’s favorites. A new edition of 300 differently painted owls of this same shape were produced in 1952. In 1958 another edition was created, this one of 200 pieces (the smallest edition of this particular form), not with a white glaze but just the terracotta clay as the mat finish. Ten years later, in 1968, Picasso decorated two more owls in his most complex and colorful design, each editions of 500. A year later, in 1969 just a few years before his death Picasso returned to the shape again with six new pieces — some of his last ceramics, also in large editions. If you add up all the edition owls of this particular shape the total comes to 5,250. Since some shapes were painted just once by Picasso in editions as small as 25, it is safe to say that these owls not only are not rare, they are actually among the most common of the three-dimensional Edition Picasso ceramics.

Now consider these four different versions of the form — all from 1969 — and therein lies the mystery:

These owls are regularly estimated at about $6000 – 8000 at auction. However, one of them — or I should say a piece from one of these editions — sold at Sotheby’s London on March 19, 2013, for the equivalent of $75,590.

These owls are regularly estimated at about $6000 – 8000 at auction. However, one of them — or I should say a piece from one of these editions — sold at Sotheby’s London on March 19, 2013, for the equivalent of $75,590.

Was that particular version some kind of weird rarity? No, it was simply one of the 500 copies in the edition, which are all supposed to be virtually identical replicas of Picasso’s prototype. Is one of these versions somehow “better” than the others from 1969 (or all the other 5,249 Edition Picasso owls of this shape)? No. In fact these four ceramics are often miscatalogued because they resemble one another so closely and because of their muddy palette they have historically sold for less than some of the more colorful pieces of the same form.

So what gives?

I have spoken about the wild price fluxuations in Picasso Ceramics before, which started with the “Madoura” sale at Christie’s London in June 2012. A lot of it boils down to a thinly traded market, lack of information and clever people trying to exploit one another. The $75,590 owl was Ramié 605, the first owl in the second row, but the huge price wasn’t made at the 2012 Madoura sale. While a copy of Ramié 605 did soar in that sale above its 3000 – 5000 British Pound estimate to achieve 10,625 pounds ($16,554), which was in fact a record high for the ceramic, that price was bested at the Sotheby’s London 2013 sale by almost 400%.

At Sotheby’s 2013 sale several other Picasso ceramics achieved prices higher than pieces from the same editions had at Christie’s historic Madoura sale the previous year. Perhaps the reason was that Sotheby’s, taking a cue from its competitor, had started to specifically target Chinese and Russian buyers. These collectors were already spending big money at the evening sales of Picasso paintings and drawings, the estimates of most of which started at over a million bucks. It was — for them — a new notion that they could pick up Picassos for less than $100,000. So you paid two or three times the estimates – the auction houses often kept estimates low just to get the action going. What bargains!

Of course when you are dealing with a lot of clever people all of whom are trying to outsmart one another reversals aren’t uncommon. There’s probably even Chinese and Russian words equivalent to the one we use in English when there’s a second reversal after the first: the double cross. Lately it’s come to light that some Chinese buyers haven’t paid for items they’ve won at auction. So perhaps once the buyer had a chance to consider things, the record price was something that existed only on paper (and in auction records), not in fact. And maybe underbidders researched the market a bit more thoroughly after the $75,590 record. Six copies of Ramié 605 have traded at auction since 2013 at prices ranging from $15,000 – 20,000 (Ramié 604, 606 and 607 have performed similarly).

Every sale is different, and when you are dealing with thinly traded items anything is possible. You only need two bidders to make an auction. If they both have a lot of money and perhaps not enough information then the sky’s the limit. The owl below, one from an edition of 300, just sold (18 March 2015) at Sotheby’s in London for 37,500 pounds ($55,343) against an estimate of about $4,400 – 7,300. At the same sale four other versions of owls of this shape sold for between $13,000 and $24,000.

There’s one more wrinkle to this story. After the $75,590 record, knowledgeable collectors who had copies of Ramié 605 (or Ramié 604, 606 and 607) decided that their ceramics, too, were suddenly worth $75,000. Not surprisingly they haven’t been overanxious to consign the pieces to auction where they are still estimated $6,000 – $8,000, and it’s hard to find a dealer with one of these pieces whose asking price starts at lower than $75,000. Thus while demand remains strong the supply actually available for sale is far less than the real supply. Just a few birds fly out periodically, which may be why they still bring Madoura Sale prices.

There’s one more wrinkle to this story. After the $75,590 record, knowledgeable collectors who had copies of Ramié 605 (or Ramié 604, 606 and 607) decided that their ceramics, too, were suddenly worth $75,000. Not surprisingly they haven’t been overanxious to consign the pieces to auction where they are still estimated $6,000 – $8,000, and it’s hard to find a dealer with one of these pieces whose asking price starts at lower than $75,000. Thus while demand remains strong the supply actually available for sale is far less than the real supply. Just a few birds fly out periodically, which may be why they still bring Madoura Sale prices.

But if everyone gets nervous that the market won’t sustain these prices and a few dozen or hundred (or thousand) owls were to fly out at the same time, look out below.

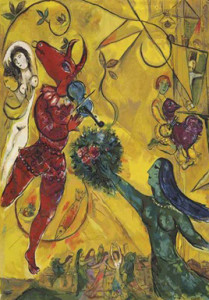

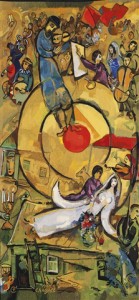

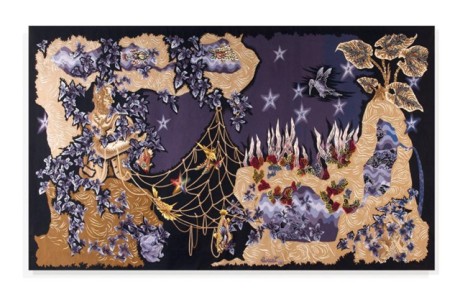

Chagall (and other) Tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince

The name Yvette Cauquil-Prince is virtually synonymous with the term “Marc Chagall tapestry.”

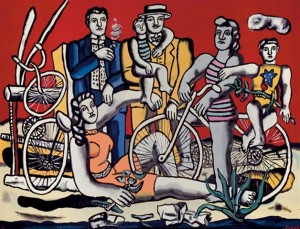

After all, Chagall didn’t spend years mastering the ancient craft of weaving and then sit working at a loom, day after day, for months at a time. Someone else had to do that, and for Chagall — as with artists and their estates including Picasso, Leger, Calder, Kandinsky, Klee, Ernst, de St. Phalle, Brassai and Matta — it was Yvette Cauquil-Prince.

The Belgian-born Cauquil-Prince was Chagall’s best option to continue to explore the medium of tapestry which he had become enamored with after completing a series of tapestries commissioned by the state of Israel. The Chagall tapestries that still decorate the state reception hall of the Knesset had been woven by the Gobelins, the famous French “Manufacture Royale” which was set up by Louis XIV but to this day only takes on gifts of state. Happily Madeline Malraux, the wife of the France’s Cultural Minister Andre Malraux, was acquainted with Yvette Cauquil-Prince and made the introductions.

Chagall was wary at first, demanding that their first effort be destroyed if he didn’t like it. Yvette had a condition of her own — that it be destroyed if SHE found it wanting. Happily both were delighted, and they embarked on a long collaboration and friendship so close that Chagall referred to Yvette as his spiritual daughter. As had Picasso, the artist allowed Yvette to choose the images to be translated into tapestry and didn’t interfere with her interpretive cartooning or weaving as it progressed. After Chagall’s death Yvette remained close to the artist’s family and with their approval continued to create Chagall tapestries, something that Chagall himself had said he wanted. “When I am no longer here, you must continue the work,” he told her. “There will never be a tapestry by Chagall without you.”

Altogether there were only about forty Chagall tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince, some of them monumental in size, all of them very small editions or unique (though “editions of one” often provided for an artist proof reserved for the Chagall family). She didn’t actually weave most of these pieces herself. Early in her career Yvette had developed a complex shorthand code by which other weavers in her employ could execute her complex Coptic-influenced interpretative designs — the blueprints that made a Chagall tapestry a Chagall tapestry. By the end of her life in 2005 it could take Yvette up to a year to complete one of these “cartoons” for tapestry.

Cauquil-Prince was recognized by the Louvre as a great artist in her own right, and her Chagall tapestries are widely honored in important private and public collections throughout the world. Because such tapestries are much rarer than Chagall paintings the temptation is to call them “priceless” since they rarely come up for public sale. However, everything has its price and during her lifetime most of Cauquil-Prince’s tapestries were for sale (this was how she made her living). They come back onto the market from time to time.

Two of arguably the most beautiful small Chagall tapestries recently appeared at auction. “Liberation” was withdrawn from Sotheby’s New York sale of November 7, 2013. Perhaps the consignor was nervous about it making the presale estimate of $200,000 – $300,000 and sold it privately before the auction. If so, he may have acted too quickly, judging by the very comparable “La Danse” tapestry, which sold at Christie’s London on February 5, 2015, for the equivalent of $306,621 USD. The presale estimate for La Danse was $152,928 – 229,392 USD, reflecting the lower prices that tapestries by other important artists have recently achieved. All tapestries are not created equal, of course. In the last ten years three other small Chagall tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince have sold at auction at prices between about $30,000 – $80,000, and one monumental masterpiece brought $385,000 – still the auction record for a Chagall tapestry.

Cauquil-Prince and Chagall were so attuned that Chagall himself declared upon seeing one of her efforts, “This is a real Chagall. It is my hands that did all this.” Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Yvette’s Chagall tapestries sell for higher prices than her interpretations of the works of other artists. However, it would be hard to make a case that Cauquil-Prince’s weaving of Leger’s “Les loisirs sur fond rouge” isn’t a spectacular tapestry. Why, then, did it sell at auction for 45% less than the top Chagall? It’s not like Leger is somehow a less important or desirable artist, at least in terms of public sales of paintings. The highest price for a Chagall painting at auction was $14,850,000 versus $39,241,000 for the top Leger lot. If you add up the top ten auction sales for each artist Leger still wins hands down — his top ten sales add up to nearly $176,000,000 versus just $100,000,000 for Chagall.

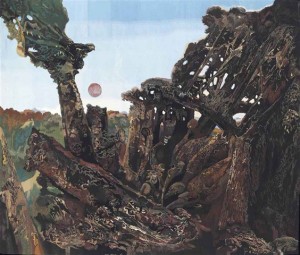

I often write about value mysteries and in many ways every sale of a work of art qualifies as a mystery. It’s no more strange that Yvette’s Chagall tapestries bring more at auction and than her Legers than the fact that Chagall tapestries are sometimes priced 1000% higher in galleries than they likely can be resold for at auction. However, the real mystery has to do with the tapestries that Yvette Cauquil-Prince created with Max Ernst.

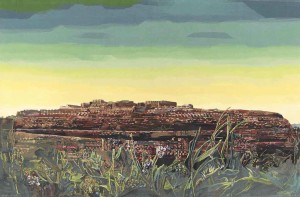

Monumental Max Ernst tapestry by Yvette Cauquil-Prince: “La ville entière” – 111 7/8 x 169 1/2 inches

Ernst (2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976), was a German born Dadaist/Surrealist. His work can be seen numerous important museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim, the Hirshhorn, Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the St. Louis Art Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art and on and on. He sells well at auction. Ernst’s top sale was $16,322,500 vs, $14,850,000 for Chagall, though if you look at the top ten auction prices Chagall thrashes Ernst two to one (why auction prices can be hugely deceptive indicators will be to subject of a future post).

Yvette Cauquil-Prince’s collaboration with Max Ernst actually came about smack in the middle of her triumphant work with Chagall. Chagall called Yvette “my little girl” once too often in front of his jealous wife, Vava, and she banished Cauquil-Prince from working with her husband for a decade. In 1978 Yvette came back to Milwaukee where she had been greeted so warmly upon completion of the Jewish Museum’s Chagall, to present her ten Max Ernst masterpieces,which then toured to Los Angeles and Philadelphia.

Like her Chagall tapestries, Cauquil-Prince’s Max Ernst masterpieces were beautifully interpreted, monumental in scale and woven in very small editions, some of them unique. Because of the difficulty and time-consuming nature of the cartooning and because Cauquil-Prince had to maintain an entire atelier of artisans to weave her pieces on Corsica, it’s likely that the prices for the finished tapestries were comparable to what she had asked for her Chagalls.

Ernst’s “La nature à l’aurore” tapestry (76.4 x 106.2 inches) woven by Cauquil-Prince did not fare well at auction

What makes an artist “important” and “desirable” doesn’t necessarily equate to demand across different markets. For collectors of Surrealism, important paintings by Ernst are very desirable. For an American living in the mid-West who is decorating his home, a beautiful tapestry by the famous Chagall is a lot more desirable than some beautifully weird and disturbing tapestry by Max Ernst, who is not exactly a household name in the USA. Still, you’d think that an Yvette Cauquil-Prince Ernst tapestry would be worth at least half as much as a Chagall or even a Leger, wouldn’t you?

But you’d be wrong. Not to be cynical, but value doesn’t necessarily have much to do with price, whether at auction or in galleries (it was Oscar Wilde who wrote that “a cynic is a man who knows the price of everything but the value of nothing”). The day after the small Chagall “La danse” sold in London for the equivalent of $308,000 against an estimate of 100,000 – 150,000 GBP, a monumental (111 7/8 x 169 1/2 inches) Cauquil-Prince Max Ernst tapestry, “La ville entière” was passed a few miles away at Christie’s South Kensington against an estimate of just 10,000 – 15,000 GBP — about $16,000 to $24,000!

“Totem et Tabou” – Max Ernst tapestry by Yvette Cauquil-Prince measuring a gigantic 163.4 x 194.9 inches

It’s tempting to think that this was some kind of bizarre fluke, but in fact Cauquil-Prince tapestries by Max Ernst have a history of making prices vastly lower than what it would cost to weave them. Christie’s didn’t just pull their estimate out of a hat, it was probably based on Cauquil-Prince’s weaving of Ernst’s “La nature à l’aurore” which sold at Sotheby’s New York on December 15, 2014 for just $22,500. And it’s not like Sotheby’s was throwing their piece away — they had offered it at an estimate of $25,000 – $35,000 on May 8, 2013 and it had failed to sell (it had brought $36,000 at a 2006 Christie’s sale). “Totem et Tabou,” which is the largest and arguably the most important of Cauquil-Prince Ernst tapestries, was passed at Christie’s London on February 7, 2013 with a much more aggressive estimate — 50,000 – 70,000 GBP (78,480 – 109,872 USD).

Bottom line, there just isn’t much demand for Max Ernst tapestries, Yvette’s talent notwithstanding, which to my mind makes them fantastic bargains (provided you like the work of Max Ernst). But auction results can be extremely deceptive indications of prices in the real world. Unless you have a time machine, knowing what was available last year (or yesterday) isn’t worth much. For thinly traded items like tapestries, the “spread” between bid and ask prices can vary wildly. Yes, “La ville entière” may have failed to get a $16,000 bid at Christie’s but it was snapped up within days after the sale. It may very well show up in some dealer’s possession tomorrow with an asking price of hundreds of thousands of dollars, which may be what it really is “worth” but would make it no bargain at all.

Art Consultants and the Agency Problem

When I was Director of a New York City gallery people often came in, saw an artwork they liked and then sent someone whom they called “my friend,” or “my dealer,” “my adviser,” or “my expert” to look over the piece and negotiate for them. Today more and more collectors are buying art through this kind of of representative. In fact there’s a whole profession of people calling themselves “art consultants.” I’m now one of them.